As originally imagined by the book writer Joe Masteroff and the songwriting team of Kander and Ebb, Cabaret was going to be a naturalistic musical. Loosely based on Christopher Isherwood’s novella Goodbye to Berlin and its subsequent dramatic incarnation as I Am a Camera, it would tell the now-familiar story of Sally Bowles, a not-very-talented English nightclub singer living in “divine decadence” on the precipice of the Nazi calamity. It would also touch on the lives of other Berliners whom Isherwood (called Clifford Bradshaw in the musical) met as an English tutor and lightly fictionalized, including his spinster landlady and her outré tenants. These characters would act and sing in much the same way characters had acted and sung since Show Boat.

But somewhere along the way, the director, Hal Prince, had an idea — what we now grandiosely call a concept — that would change not only Cabaret but the future of the form. His idea was to fracture the traditional musical-theater narrative by interrupting “book” scenes and character-based songs with numbers sung in a grotty club by a creepy emcee and the house entertainers. These numbers would comment on and generalize the book situations, giving us (for instance) the naughty vaudeville ditty “Two Ladies” at the moment Sally suggests, daringly for 1929, sharing Cliff’s tiny room and bed. The effect was designed to be both alienating and seductive: Like the sybaritic bon vivants of late Weimar Germany, the audience would be led by the pleasures of a floor show to suspend its moral judgment — at least until the first swastika appeared at the end of Act One.

It’s hard to appreciate how powerfully this new concept affected audiences in 1966. Artists, too: Later musicals as diverse as Follies, Chicago, and Dreamgirls adapted (and advanced) the Cabaret template. By the time the director Sam Mendes was preparing a revival for the Donmar Warehouse in 1993, the once-daring dramaturgy therefore seemed old hat. For one thing, there was so much more it was possible to say and show onstage. Explicit violence and nudity, once deemed vulgar, was now de rigueur. The horrors of Hitler, perhaps too fresh just 21 years after the end of the war, could be addressed more directly another 27 years on. And varieties of love could at last be treated frankly, or franklier. From the book to the play to the musical to the movie, Cliff’s sexuality had been finessed more ways than a clownfish’s; now he could be — well, whatever he is. Bicuriously gay?

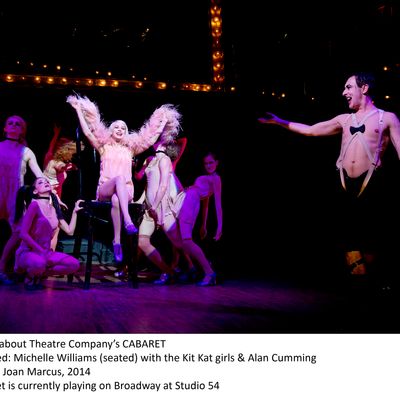

Leaping at these opportunities, the Mendes Cabaret, especially as restaged in New York by the Roundabout in 1998, with Rob Marshall choreographing and co-directing, proved to be one of the greatest reconfigurations of a classic musical ever. (It didn’t hurt that it always had one of the greatest scores, not to mention a trove of castoffs and movie additions to scavenge.) Though most of the intellectual force of the concept was already implicit in Prince’s staging, the new version developed it further, especially in honing the equivalence of entertainment and complicity to a sharper point with its realistic nightclub setting. It also emotionalized the material more completely, offering in Natasha Richardson’s Sally a good-time girl struggling gamely to rise past despair. And, in the character of Alan Cumming’s Emcee, who teases but then is crushed by conformity, it muddied the distinctions between observer, satirist, collaborator, and victim.

Is it too much to ask that the current revival of the revisal of the reimagining of the great work still be as good? After all, the Roundabout production opening tonight at Studio 54 is much the same show as the one that closed there ten years ago. The orchestra seats have again been replaced by 93 tables with red-shaded lamps and offers of “Don’t Tell Mama” cocktails. The orchestrations and arrangements remain top-notch. Robert Brill’s trademark peep door and tilted picture frame are lit as luridly as ever, and William Ivey Long still gets great mileage out of the costumes’ tawdry stabs at glamour. But if none of that has changed, we have — at least by having seen this Cabaret before and treasured it in memory. The reality, in some ways, can’t help but fall short. “This same production in ten years would probably look very tired if we remounted it,” Kander himself predicted in 2003. Ebb, who died the next year, added, “It would probably look tame.”

I’m not sure you could call Cumming, with his rouged nipples and S&M undergear, tame; certainly he’s tireless. But as the only holdover cast member, he’s also the only one with a need to articulate a deeper understanding of his character. I’m not sure this can be done with a character who is a concept; at any rate, Cumming over-articulates the Emcee, illustrating every word he speaks like a mime instructor. Some of the punch lines get killed by the huge pauses he takes to set them up. In general, the less business he has, the better; his rendition of “I Don’t Care Much” — a song originally assigned to a prostitute — is ravishingly unadorned.

The performers who make the most of their material are in fact the two who have the least background in musicals. Michelle Williams’s head voice is breathy, with a hummingbird vibrato; her belt is solid if somewhat coarse. But these are not handicaps with Sally, and in any case she acts the hell out of the role. When we first get an eyeful of her, in a platinum bob and a pink babydoll negligee, she already looks, as she madly smiles, like she’s ready to break. You understand why Cliff (the solid Bill Heck) both adores and distrusts her. Not even Richardson, superb as she was, brought quite this sense of brimming irrepressibility to the role: irrepressible eagerness and irrepressible sorrow. And, somehow, both together.

The other great discovery here is Linda Emond (such a fine Linda Loman two seasons ago) as the landlady, Fraulein Schneider. Since this character exists only within the traditional part of the narrative — her story concerns a doomed love affair with a Jewish fruiterer, played well by Danny Burstein — her songs are less abstract; they express character directly. Emond, who has, it turns out, a terrific singing voice, uses it as naturally as speech, and in that way manages to exemplify the show’s greatness without seeming to perform it. Indeed, it’s an irony of this production, which for all my quibbles is nevertheless excellent and needs to be seen, that it is most excellent in the old ways: the pre-Cabaret ways.

Cabaret is at Studio 54 through January 4.

*This article appears in the May 5, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.