Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations, and you should read as many of them as possible.

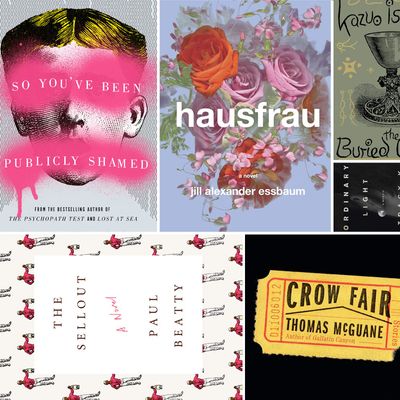

The Buried Giant, by Kazuo Ishiguro (Knopf, March 3)

Ishiguro is a deft gut-renovator of genres, bringing fresh life and feeling to hollowed-out conventions. A full decade after his last novel, Never Let Me Go, turned a Twilight Zone plot into a profoundly sad romance, Ishiguro’s belated seventh novel is a dungeons-and-dragons quest set in post-Arthurian Britain — a land at uneasy piece, cursed with an amnesiac fog that might be the breath of a she-dragon. Even for Ishiguro, it’s a bold departure: highly stylized, alternately stiff and swashbuckling. But the love story at its center shimmers with a mythic and melancholy grace.

The Sellout, by Paul Beatty (FSG, March 3)

From the lawn jockeys on the cover to the last bawdy joke, Beatty does not treat race delicately. His latest satirical-absurdist novel, an exuberant parade of forbidden words and twisted stereotypes, is narrated by the resident of an L.A. “ghetto community” zoned for farming. To prevent it from gentrifying, he embarks on a program of resegregation with the help of a voluntary “slave,” the last surviving member of a racist version of The Little Rascals. Then the Supreme Court steps in. It’s incendiary fun with very serious undertones; just don’t read it out loud.

A Little Life, by Hanya Yanagihara (Doubleday, March 10)

The author of the disturbing anthropological mystery The People in the Trees trades in her debut’s geographic breadth for intense emotional depth. What starts as the story of a clique of four college friends making it in New York spirals inward to dissect the past and present torments — physical and psychic — of Jude, their most mysterious member. There’s nothing little about this book: not its length or its pleasures or its sometimes-wince-inducing tortures. Jude’s story is cathartic in the truest sense; it’ll wring you out like a sauna.

Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania, by Erik Larson (Crown, March 10)

The author of The Devil in the White City shows that narrative history can let us have it both ways: great drama wedded to rigorous knowledge. The German torpedoing of the great ship 100 years ago was almost as deadly as the Titanic sinking, and far more world-changing. Larson makes it feel as immediate and contingent as the present day. So much had to happen for the Lusitania to sink, while only one deviation would have saved nearly 1,200 passengers. By the end of the book, we feel as though we’ve gotten to know — and mourn — most of them.

Crow Fair, by Thomas McGuane (Knopf, March 15)

More stories from the wry bard of the High Plains display the full range of his talent for mashing up the pastoral and the domestic — dragging the petty squabbles, infidelities, and tragedies of modern life out under Montana’s big sky like tacky sofas left to rot in America’s backyard. McGuane’s broken character — a couple stuck in a shallow affair, two lifelong frenemies stuck with a nutty camping guide, a divorced dad courting his son’s affection on a fishing trip — seek solace and affirmation from the outdoors, with generally disastrous results.

Hausfrau, by Jill Alexander Essbaum (Random House, March 17)

The poet’s first foray into fiction has already drawn references to Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina — stories of unhappy homemakers unraveling. (Essbaum encourages them by starting her novel, “Anna was a good wife, mostly.”) But the self-alienation of the American wife of a Swiss banker, resulting in Jungian analysis and reckless serial adultery, feels more contemporary, subjective, and just plain funny than classical bourgeois ennui. Imagine Tom Perrotta’s American nowheresvilles swapped out for a tidy Zurich suburb, sprinkled liberally with sharp riffs on Swiss-German grammar and European hypocrisy.

So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, by Jon Ronson (Riverhead, March 30)

The author of The Psychopath Test has a knack for finding scenic byways into our collective lunacy. Here the age of social-media shaming gets the writer it deserves. Ronson talks to its far-flung victims (Justine Sacco, et al.) and traces its roots in history (from witch trials onward) and psychology (our innate mob-think). His chronicle, in which no one is blameless but few deserve what the web has allotted them, is both entertaining and fair — a balance we could use a lot more of, online and off.

Ordinary Light, by Tracy K. Smith (Knopf, March 31)

After winning a Pulitzer Prize for a collection of science-fiction-premised poetry (Life on Mars), Smith turns abruptly to prose in every sense. Her memoir is about a life in many ways ordinary — suburban California upbringing, elite college education, upward mobility and black assimilation. Even her mother’s untimely death isn’t all that anomalous. But her writing is both precise and transcendent, so that when Smith digs deeper into her black rural roots — origins her parents were eager to put behind them — her revelations about identity, religion, and family feel as momentous as anything Barack Obama once put between covers.

*This post has been corrected to show that Hausfrau will be released on March 17, not the 24th.