“We, like many people, knew Frida Kahlo as one of the most important artists of the 20th century — and, dare I say it, as a cultural icon,” Todd Forrest, vice-president for horticulture and living collections at the New York Botanical Garden, quipped at the press opening May 16 for “Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life.” Heck, the Times “Styles” section had just the week before declared that the artist was “having a moment.” “But we as gardeners were completely unimpressed with those two things. When we learned about Frida Kahlo as a sophisticated gardener, we were blown away.”

In other words: You may know of Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits and you may know of her love affairs, but you have no idea how handy she was with a hoe and a rake. “As an art historian, I’m very interested in contributing to the conceptual basis of Frida Kahlo’s work,” guest curator Adriana Zavala said. “There are a lot of scholarly essays, exhibitions, and monographs that focus on Frida Kahlo’s biography and then use her artworks to plot the course through the events of her life. I’m not saying that that’s not appropriate, but it’s not something that particularly interests me.” Instead, she wants to get down into the actual dirt with her, which the show enables you to do.

The first solo exhibition of Kahlo’s work in New York in ten years, and coming on the heels of a well-publicized exhibition in Detroit, the show offers a refreshingly interdisciplinary take on an artist whose notoriously tempestuous marriage to philandering muralist Diego Rivera tends to overshadow her work (it’s also what the Detroit show focused on). Bridging the gap between art history and horticulture, it brings out Kahlo’s fascination with plants, both in her verdant paintings and in her house garden in Mexico City, where she and Rivera cultivated a paradise of locally sourced flora.

All this makes the show at the Botanical Garden much more than a convenient tie-in, or a gimmicky theme show. Far from benign decorative motifs, plants — much like Kahlo’s famous Tehuana dresses and thick braids and wide eyebrows — were potent symbols of Kahlo’s sexual identity and oppositional ethnic politics.

Throughout the 1930s, Kahlo and Rivera renovated her bourgeois neoclassical house, painting its walls that now-famous shade of indigo-blue and substituting the garden’s roses and ferns her father had planted with agave, columnar cacti, palm, and yucca — plants either indigenous to Mexico or otherwise “exotic” in appearance. An Aztec-inspired step pyramid was installed in the center of the garden to display Rivera’s collection of pre-Hispanic artifacts. In the Botanical Garden’s Enid A. Haupt Conservatory, Forrest and his team have meticulously replanted various stages of Kahlo’s garden, taking cues from archival photographs and botanical details from her paintings to reconstruct what he called “the most important and beautiful gardens in the world.”

In the LuEsther T. Mertz Library, there is an intimate selection of 14 of Kahlo’s lesser-known paintings and drawings abundant with vegetal imagery and sexual metaphor. Several gynocentric still lifes feature tropical fruits — guavas, mangoes, watermelon, sapodilla, cactus, and mamey fruit — some of them halved and splayed to resemble female genitalia. The 1944 painting Flower of Life fuses two species of flower into a red, engorged phallus with a poinsettia base, with an angel’s trumpet as a shaft, and ejaculating pistil and stamens; it was deemed too explicit for the general public and shown in a separate room when it was initially exhibited. Yet, despite its obvious phallic symbolism, Flower of Life is also hybrid and hermaphroditic. The poinsettia’s skirt of petals inescapably connote labia; as exhibition coordinator Mia D’Avanza explains in the exhibition catalogue, Kahlo “correlated the flower of the angel’s trump to fallopian tubes without ovaries” in a likely reference to her inability to bear children, a problem that pained the artist thought her life.

And there’s the metaphysical, almost Blakean Sun and Life, in which a red sun with Diego Rivera’s face and a weeping third eye is ensconced in a field of stylized aroid plants flowering with penises, vaginas, and human fetuses.

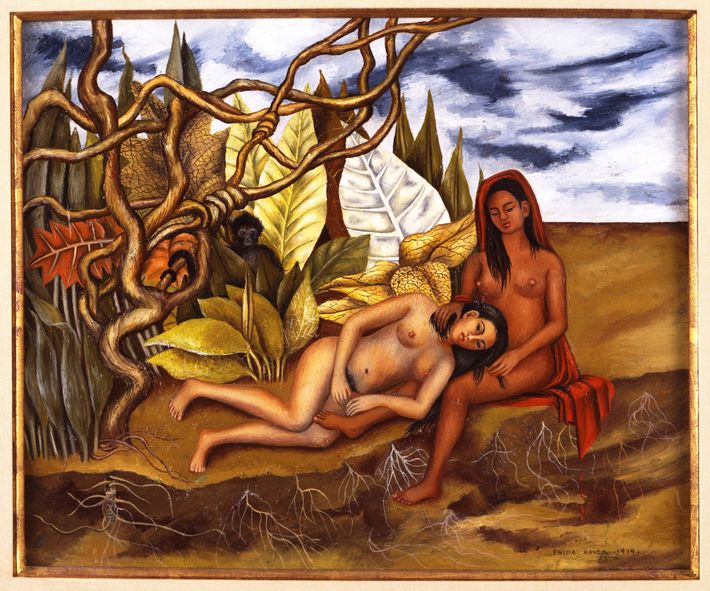

While the analogy between Hispanic women and nature might seem hokey, naïve, or essentialist today, Kahlo’s appeal to the natural world was a powerful metaphor against racist and misogynistic ideologies. Painted for actress Dolores del Rio — Kahlo’s friend and, some have said, lover — Two Nudes in a Forest depicts a white woman nestling her head in her indigenous partner’s lap, as they rest at the edge of a tangled jungle overgrown with alocasia, sanseveria, and philodendron. The work is both personal and political. It can be read as thinly veiled lesbian erotica and, at the same time, as an allegory for Mexico’s national discourse of mestizaje, which aimed to stamp out the legacy of colonial racism and unite the country’s white and aboriginal heritages.

“In the aftermath of the Mexican revolution, a symbolic discourse of mixture — or mestizaje — emerged very powerfully as a way for the nation to reconcile its cultural divisions,” Zavala noted during the press preview.

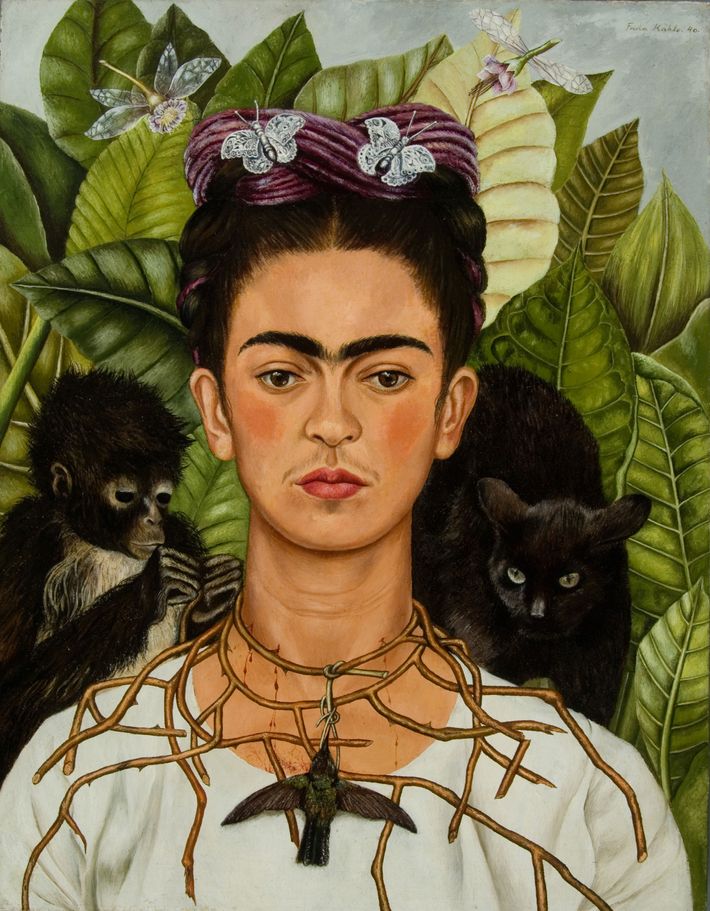

In Self Portrait With Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird — perhaps the most recognizable painting in the show — Kahlo’s iconic likeness appears against an impenetrable façade of thick green vegetation. Flanked by a monkey and a black cat, she wears a dead hummingbird around her neck as a talisman. In a whimsical touch, two winged flowers hover on either side of Kahlo’s head like cherubs in religious works. The painting is a sterling example of Kahlo’s rightfully celebrated self-portraits, but the show’s highlight is the wonderfully bizarre Portrait of Luther Burbank, depicting the distinguished American horticulturist — renowned at the time for cultivating thousands of new varieties of fruits and vegetables — as a man-plant hybrid. Transformed into an unlikely Earth goddess, Burbank holds a budding philodendron, often depicted as a fertility symbol in ancient Aztec codices. The suit-clad, silver-haired celebrity scientist’s tuberous, tree-trunk legs germinate from an interred cadaver, sprouting from the Earth as a surrealistic human mullet: culture up top, nature down below.