Joey Bada$$ Was Having a Pretty Bad Day at This Year’s Summer Jam

Three members of Brooklyn’s Pro Era rap crew — Dessy Hinds, Kirk Knight, and Sür Niles — are sitting in a parked rental van near Manhattan’s Port Authority Bus Terminal waiting for Joey Bada$$. They were scheduled to join him during his performance at Hot 97’s annual Summer Jam Festival at the MetLife Stadium in New Jersey later that afternoon, and this was their rendezvous spot. “Yo, dead ass, Joey always comes mad late,” says Dessy, 21, noshing on a breakfast sandwich from a deli across the street. He isn’t complaining, just stating a fact. No one seems to mind Joey’s tardiness all that much, and when he suddenly arrives just shy of an hour late, he climbs into the van and immediately pulls his hat over his eyes as a silent, not-so-subtle gesture to be left alone. The hat stays that way during the 15-minute drive to East Rutherford. Nobody bothers him.

Jo-Vaughn Virginie Scott, better known by his stage name Joey Bada$$, grew up in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, near the Holy Cross Cemetery, in the same neighborhood as Bobby Shmurda. His debut albumB4.DA.$$ is considered one of the year’s best. Instead of the trap beats you hear all over rap radio, it prefers boom-bap, a drum-and-bass sample technique dominant in New York back in the early 1990s. Joey is only 20, and his mom says he started rapping at age 6, when his rap name was Jay Six the Spy Kid. By 17, he had some of the biggest producers in hip-hop in his corner, including MF Doom, Statik Selektah, DJ Premier, and Lord Finesse, all of whom worked on his debut mixtape, 1999. Like Shmurda, Joey was aggressively pursued by labels once his self-released music gained momentum online. Shmurda signed a seven-figure deal with Epic Records and ended up in jail. Joey met with and turned down a personal offer from Jay Z. In January, his rap collective Pro Era became a national sensation when a mysterious selfie of Malia Obama wearing a shirt bearing their logo made its way online. Eager to put the story to rest, Joey says the shirt was “a gift from a mutual friend of hers and Pro Era,” and leaves it at that.

At Summer Jam, we file out of the van and into Joey’s dressing room. He’s still not talking. He’s not feeling well. He’s thinking about canceling the show. This is a very awkward interview. The blunts come out. Everyone begins smoking and picking at a tray of cookies and potato chips. Joey opens up — just a little.

Capital Steez, Joey’s close friend, founded Pro Era in 2011 and modeled it after Odd Future, the controversial California rap collective that spawned independent careers for Tyler, the Creator, Frank Ocean, and Earl Sweatshirt. “They definitely inspired us when we seen a group of kids on the West Side coming together to do something,” says Joey. “It probably wasn’t considered positive, but their movement to us was very positive because they were kids, and they could have easily betrayed their path, but instead they came together. That really inspired us to create a prenatal Pro Era. It was like, Yo, it’s no way that we couldn’t do it, too.”

Unlike the early days of hip-hop, when the dynamic between East and West was bloody and violent, Joey feels a kinship with his California peers, especially Kendrick Lamar. “Kendrick Lamar is headlining today, and he’s a real artist,” he says. “I haven’t seen that in years, and I’ve been coming to Summer Jam since I was a child. I fuck with everything that Kendrick does because I know that he’s a real artist. I know that he’s not going to conform or change his style for no one.”

Joey’s parents split when he was 5, but both have been supportive. His mother, Kim, handles all of his finances and ships Pro Era merchandise directly from her home in Brooklyn. “With Pro Era, Joey had a vision,” she says. “He knew what he wanted to do,” and so he remained independent. B4.DA.$$ sold 58,000 copies in its first week and landed Joey at No. 5 on the Billboard 200. “His numbers are mainstream numbers, but he makes music for him as opposed to what we’re told is cool on the radio,” says Statik Selektah, Joey’s frequent collaborator and DJ. “I think now he has the option to do what he wants to do, but he had to prove that he could be indie first.”

Not everything is coming up daisies for the young rap prodigy, though. In January, he was arrested for assault during a show in Australia when a security guard saw him running backstage, mistook him for someone who wasn’t authorized to be there, and clotheslined him. Allegedly, Joey punched him in the face, and the guard ended up hospitalized with a broken nose. Joey had to cancel a gig in Africa to return to Australia for a court date. “They’ll probably fine him,” says Statik, “and put him on Australian probation, which, what the fuck is that?”

It was Joey’s first and only major run-in with the law, but many of his young black and Latino peers aren’t so lucky. “At the end of the day, he’s 20 years old, he’s young, he lives in an urban area, and he’s not much different from a lot of the kids that these things are happening to,” his mom says. “At any point, at any time, it could possibly be him or a friend. He has had friends that these things have happened to. We had a next-door neighbor that was a victim of a police shooting. So Joey is aware of these things, and what’s going around him.”

Joey carefully opens a packet of Emergen-C and pours it into a bottle of Vitaminwater. He’s still not feeling well. He takes a seat on a couch and closes his eyes. There’s a din inside the dressing room, but Joey is sitting quietly, like he has a lot on his mind and is saving his energy for the show. Backstage, he says he doesn’t want to talk about police violence because “I’m coming out of a bad mood. I don’t want to go back into that mood again.” Later that night, a riot between security and festivalgoers not yet let into the venue broke out in the MetLife parking lot. Police responded with armored vehicles, pepper spray, and tear gas.

You can glean Joey’s thoughts through his music and his actions. In the video for “Like Me,” he plays an innocent and unarmed black kid running from and eventually shot by the police while his hands are in the air. His song “No. 99” features visceral lyrics on race and gross police violence. During shows, he often chants “fuck the police” from stage. He makes appearances at national protests against police brutality. It all comes back to Pro Era, which now has 47 members, all of whom support Joey’s commitment to tackling social issues affecting young black men. It’s like a family, says Dessy. “That’s really what it is. Pro Era is just us.”

Capital Steez committed suicide in December of 2012, when he was only 19. To commemorate his death, Joey launched the annual Steez Day Festival in Brooklyn. “Last year, we threw what was basically the first Steez Day,” he says. “It was just a gathering in the honor of Steez, but it turned out to be something so big. We told everybody to meet us in Prospect Park, and I was blown away with how many people came out. It was so many kids, it was crazy. It was such a positive environment. The cops came through, but they peeped that it was just positive energy. There was nothing to break up. It wasn’t anything negative. They just left us alone and we just had a good time.”

For this year’s Steez Day, Pro Era has decided to take it to another level. It’s an official festival, complete with a lineup of small local hip-hop acts. “Last year was totally informal. This is the official, annual Steez Day,” says Joey proudly, finally eager to talk. “We are going to do this annually for now on, on his birthday, July 7.” Joey flashes a smile and looks out a window before getting ready to go onstage. For the first time all day, he seems genuinely happy.

Joey pulls his hat over his eyes on the way to Summer Jam.

Photo: Christaan Felber for Vulture

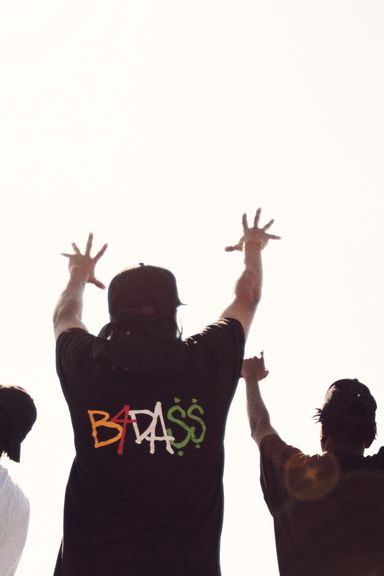

Dessy, Kirk, and Joey light up backstage.

Photo: Christaan Felber for Vulture

Kirk, Joey, and Dessy.

Photo: Christaan Felber for Vulture

The Summer Jam Festival Stage crowd.

Photo: Christaan Felber for Vulture

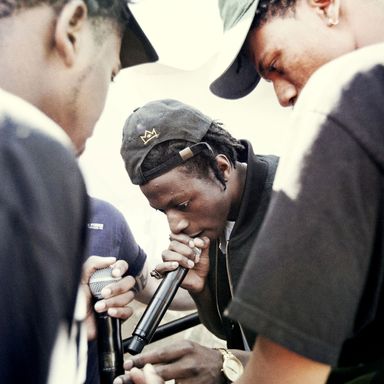

The mic check.

Photo: Christaan Felber for Vulture

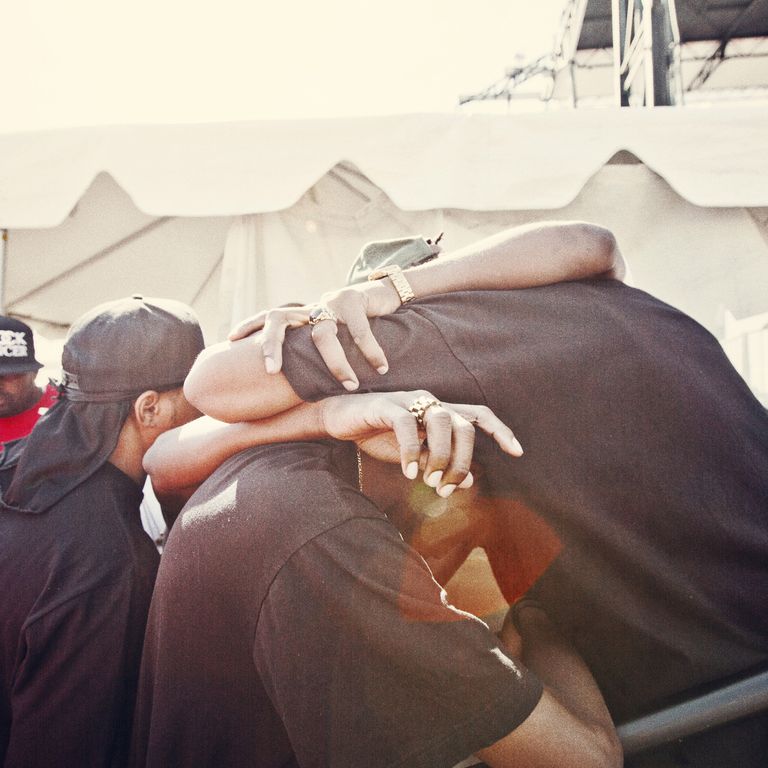

Pro Era group hug.

Photo: Christaan Felber for VultureJoey at this year's Summer Jam.

Photo: Christaan Felber for Vulture