From the start, Nina Simone was a communal dream. Very early on in the life of Eunice Waymon — that was the name she was born with, in 1933 — the town of Tryon, North Carolina, realized it had a prodigy in its midst and, since the Waymons couldn’t afford piano lessons, took up a collection to give the girl a proper musical education. There were lines in the paper advertising the Eunice Waymon Fund. Local churches took up collections; the town council raised funds. The dream — Eunice’s, the town’s, the black community’s — was that she’d someday be the first black female concert pianist to play Carnegie Hall. Eunice practiced tirelessly, crossing the railroad tracks into the white part of town every Saturday to take lessons from a woman she called Miz Mazzy. “I was a busy child, hardly stopping to catch my breath,” she recalled many years later in her autobiography I Put a Spell on You, after she’d christened herself Nina Simone. “All the time there was the weight of my community’s expectations on my shoulders.”

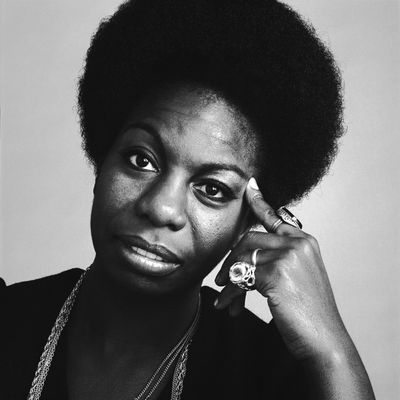

Some people say Nina Simone sounds like a man. I say she sounds like ten men, and about as many women, all wrestling inside that cavernous throat for the freedom to be finally, wholly heard. Her voice is androgynous, but in that way that communicates a kind of collectivity. Listen, right now, to the dolorous soul of “I Wish I Knew How It Felt to Be Free,” the babbling fury of “Mississippi Goddam.” That’s a heavy, haunted voice — leaden with the weight of history, expectations, and an entire community. One of those voices that has other voices in it. Some of them professionally trained singers, but most of them not. At least a few of them, probably, are ghosts.

What Happened, Miss Simone? a new documentary about Nina directed by Liz Garbus, is coming to Netflix this weekend, and it is very much worth pausing whatever show you’re currently bingeing on and giving it your attention. Watch it once, maybe more than once. I have now seen it twice, and it made me cry both times, but for different reasons. I saw it in early June, when it made its premiere at the Apollo, to a reverent silence that the theater never quite granted Nina in life. (“Friends said I might have trouble with the crowd there because the Apollo was well known for giving artists a rough time and I was well known for doing the same to audiences,” she wrote in her autobiography, of her sole performance at the venue. “In the end, we fought to a draw.”) The film is quite moving, especially in its unflinching look at Simone’s later years, and what we cried for that night was the turbulent life of this brilliant, perpetually troubled genius. I watched the film for a second time a few days after nine black people were shot to death inside a church in Charleston, South Carolina. That time I was crying for them, and the sickening inevitability of their suffering, and the songs I wish sounded dated but instead sound, so dreadfully, like they were written this afternoon. “Lord, have mercy on this land of mine / We all gonna get it in due time / I don’t belong here, I don’t belong there / I’ve even stopped believing in prayer.” Three men. Six women. All somehow wailing through the recorded voice of a woman who saw the world clearly enough to sing of pain in the past, present, and future tense.

It was almost an accident that Nina Simone ever even opened her mouth in the first place. At her first-ever paid gig, at a dive bar in Atlantic City, she only played the piano. The owner told her to sing the following night or else he’d fire her, so she sang the following night, and nearly every one after that for the rest of her life. She loved Bach and looked down on most pop music, but playing gospel in church had taught her how to improvise on the spot and take the crowd’s pulse. “I wasn’t a jazz player but a classical musician, and I improvised arrangements of popular songs using classical motifs,” she’s recalled of those early performances. “It’s not a predictable art.” In an odd way, Simone was kind of the original mash-up artist, deftly deconstructing pop songs and rearranging them in unexpected contexts. And though she wrote a few classics on her own (“Four Women,” “To Be Young, Gifted and Black”), she’d draw upon that skill to become one of her generation’s greatest interpreters. She could transform a campy trifle from Hair into an anthem of black humanity, make “Here Comes the Sun” feel like an unearthed slave spiritual, and even turn “Just Like a Woman” into a vulnerable, first-person confession.

And so those long nights in Atlantic City gave birth to the teetering, daring Zen of Nina Simone the performer. She lived in the moment, and the moment very rarely met her expectations. She had enough self-respect to ask for more out of everything — which, for a black woman then and now, is a revolutionary act. Simone became notorious for demanding complete quiet and stillness from audiences (there’s a remarkable clip in the film in which she halts a gorgeous, fragile performance of Janis Ian’s “Stars” to give an inconsiderate listener a death stare, and then somehow continues the song without killing the vibe), but really, she just wanted pop musicians to be granted the same kind of respect that audiences gave classical performers. (Part of me is glad that Nina Simone died before the advent of smartphones at concerts. Can you even imagine?) Make no mistake, Simone was something much more radical than a “diva” — she was a utopian, daring to demand more from quite literally everything life had to offer. A better crowd, a better world, a better fuck. (In the film, her ex-husband and ex-manager Andrew Stroud recalls with a shudder when Nina would have what he dubbed a “sex attack.” “My attitude towards sex,” she explains unapologetically, “was that we should be having it all the time.”)

Her early songs, though, were prim and composed relative to what came later. Simone’s first big hit, in 1958, was a rendition of “I Loves You Porgy,” from Porgy and Bess. We see her play it in one of the greatest bits of archival footage that the filmmakers have dug up, of Simone performing on Hugh Hefner’s short-lived TV series Playboy’s Penthouse. (“I’m … Hugh Hefner” is arguably the film’s biggest laugh line.) The audience is demure, TV-ready, and, most noticeable, 100 percent white.

What Happened, Miss Simone? is the story of Simone’s radicalization. (She’d later name one of her greatest songs after an unfinished play her friend and neighbor, the writer Lorraine Hansberry, was writing at the time of her death: “To Be Young, Gifted and Black.”) In the ‘60s, Simone suddenly found herself in the center of the black intelligentsia, and friends like James Baldwin, Malcolm X, and Stokely Carmichael inspired her to channel her responses to the civil-rights movement into song.

As she tells it, the day of the Birmingham church bombing in 1963, she went into the garage with the intention of making a homemade gun. She quickly gave up and wrote “Mississippi Goddam” instead. Radio stations tried to suppress it (some sent their copies of the record back to the label, cracked in half) but it captured a certain kind of urgency of the moment and inevitably became its unofficial anthem. In a lot of performances, Simone would tell the audience: “This is a show tune … but the show hasn’t been written for it yet.” And that’s the strange genius of the song: It’s antsy in its anger. Deceptively jaunty and light on its feet even as it bellows its threats directly at the (white) listener: “This whole country’s full of lies / You’re all gonna die and die like flies.” Playboy’s Penthouse this was not.

Who will write our “Mississippi Goddam”? Has anyone even tried? There’s been, of course, Prince’s “Baltimore,” J. Cole’s Forest Hills Drive, and, perhaps most in keeping with the spirit of Miss Simone, Lauryn Hill’s “Black Rage.” But aside from that, the larger musical response to the events that have unfolded in Ferguson, New York, Baltimore, and Charleston has felt unsatisfying. And it will feel that way even more so after you watch the film and see how much Simone risked in singing her truth. Though she won the respect of the civil-rights movement, she never became quite as commercial as some of her less outspoken peers, and in some ways her career never recovered from her radical turn. The risks of making political music today are not nearly as grave, and yet artists seem more reluctant to do so. A solemn Instagram or consolatory tweet too often suffices. What Happened, Miss Simone? is one of those films that brings its subject so completely to life that you start to see your world through her eyes. And like Nina, you might start asking for more.

Garbus and her filmmakers tell Simone’s story through a combination of affecting handwritten letters, archival interviews of Simone and Stroud, and new interviews with Simone’s daughter Lisa, her guitarist Al Shackman (with whom she had a deep, adorable, borderline telepathic friendship), and Malcolm X’s daughter Ambassador Shabazz (thanks to her well-connected mother, one of Lisa’s childhood playmates). The interviews flow well and shed a good deal of light on Simone’s story. But, like a respectful Nina Simone concertgoer, the film is at its best when it shuts up and lets the woman sing.

The final performance in the film is so moving that it’s been haunting me for weeks. (Luckily, it’s on YouTube.) Simone is performing in Switzerland at the Montreux Jazz Festival. It’s 1987, and she’s experiencing an unexpected resurgence thanks to a Chanel No. 5 ad that sets a montage of a white supermodel cavorting with her wealthy lover to the tune of “My Baby Just Cares for Me,” a song off Simone’s 1958 debut Little Girl Blue. “This song is popular all over France, for Chanel No. 5 perfume,” she tells the Montreux audience. “Unfortunately, I have none, and not the money either.” She reflects on how long it’s been since she recorded it, how much she’s learned. “I only wish I could have been as wise then as I have become now,” she says, gazing down into the piano keys. “I have suffered.”

She doesn’t need to say that last part; it’s there in every note of the song. The original is coquettish and light on its feet. This one is heavy, sonorous, almost violent in its virtuosity. Like every other performance in the film, it’s a potent reminder of Simone’s genius, and of her disappointment with a world that never quite lived up to her dreams. She gave us the tunes. I only wish we were finished writing the show.