Nobody owns David Foster Wallace anymore. In the seven years since his suicide, he’s slipped out of the hands of those who knew him, and those who read him in his lifetime, and into the cultural maelstrom, which has flattened him. He has become a character, an icon, and in some circles a saint. A writer who courted contradiction and paradox, who could come on as a curmudgeon and a scold, who emerged from an avant-garde tradition and never retreated into conventional realism, he has been reduced to a wisdom-dispensing sage on the one hand and shorthand for the Writer As Tortured Soul on the other.

For someone who has long loved Wallace’s writing, as I have, one of the ironies of this shift is that, whether he intended to or not, Wallace started the process himself. First, he embarked on a series of publicity campaigns in which he performed his self-conscious disdain and fear of publicity campaigns, a martyr to the market culture and entertainment industry he was satirizing in his books. Then there was a treacly commencement speech at Kenyon College in 2005 that became a viral sensation and later, a few months after his death, a cute, one-sentence-per-page inspirational pamphlet, This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, About Living a Compassionate Life. And now comes a bromantic biopic, The End of the Tour, starring Jason Segel as Wallace and Jesse Eisenberg as David Lipsky, the novelist Rolling Stone sent to write a (later abandoned) profile of Wallace in 1996. The movie’s theme is the bullshit-ness of literary fame — which Wallace, the permanently unsatisfied overachiever, nonetheless craved (not to mention it might get him laid, which he also thought would be a phony achievement). The movie is based on Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, the book of transcripts Lipsky published in 2010. And since much of its dialogue is transferred directly from the tapes, it does have a claim on the authentic Wallace.

None of this is entirely new; Wallace has always been an unstable commodity. For two decades, the writer and his writings have been at the center of a cult with several branches. The first branch is other fiction writers, who also tend to be the most serious readers. This makes a certain obvious sense. Infinite Jest is, on its face, the most daunting of novels; 1,079 pages, 96 of them endnotes; text in small type pointing you constantly to text in smaller type, necessitating multiple bookmarks; an immersion in two subcultures, junior tennis and addiction recovery; a time commitment to be measured in weeks, not days — two months for serious readers, Wallace thought. Writers took to it like Marines sprung from a sort of literary boot camp, hunting for something beyond the minimalist vogue of the 1980s.

The second branch are the magazine writers for whom his essays renewed the possibilities of a fast-aging New Journalism by clearing away Tom Wolfe’s cynicism and replacing it with a dazzling faux-amateur act.

The third are the academics; English professors hadn’t received the gift of fictional worlds so rich and susceptible to their hermeneutics since Nabokov, Beckett, or Joyce.

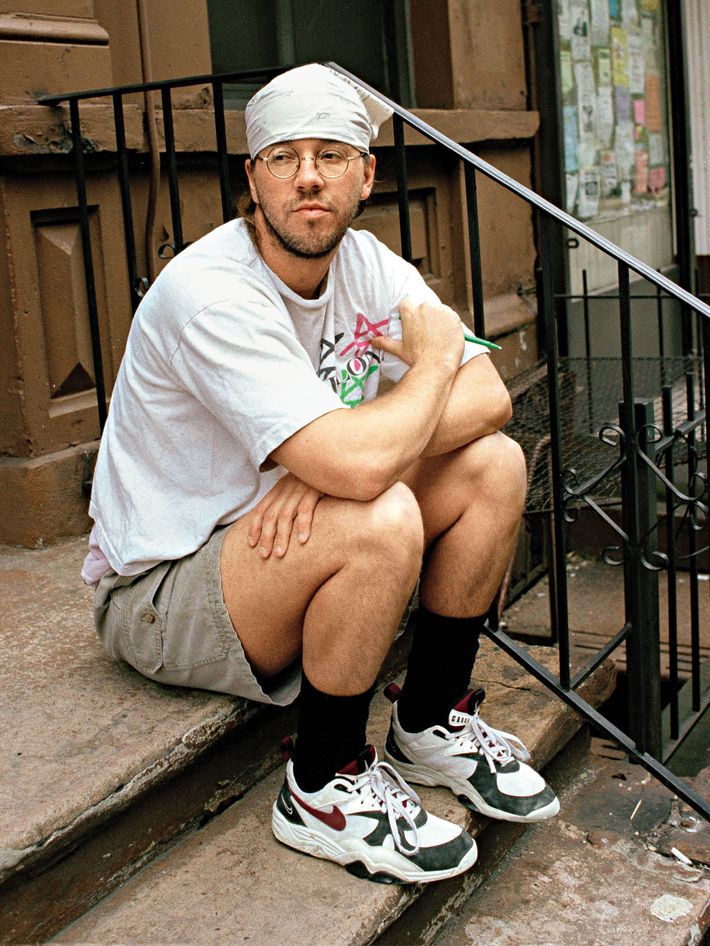

But before his suicide he compared his own fame only to that of a high-profile classical musician. It’s just since the Kenyon speech became the sort of chain email your dotty uncle forwards you that Wallace has been transformed into an idol of quasi-moral veneration, the bard of ironic self-loathing transformed into a beacon of earnest self-help. And now that he comes to the screen, bandanna and ad hoc spittoon in tow, he stands to become a hero to audiences who haven’t read a word of his work. The cult could become a church.

The Wallace estate (he is survived by his widow, the painter Karen Green, and his sister, Amy Wallace-Havens) has said it doesn’t support the movie, didn’t consent to it, doesn’t even “consider it an homage.” What would Wallace himself have said of the film, which follows him on his Infinite Jest tour, a movie about his efforts in book promotion that also accelerates his canonization? “The whole going around and reading in bookstores thing,” he told a German television interviewer in 2003, “it’s turning writers into kind of penny-ante or cheap versions of celebrities. People aren’t usually coming out to hear you read. They’re coming out to sort of see what you look like, and see whether your voice matches the voice that’s in their head when they read. None of it’s important. It’s icky.” Icky not because he felt he couldn’t play the game but because he found himself playing it so well. In 1996, he went on Charlie Rose, with friends and rivals Mark Leyner and Jonathan Franzen (long-haired and quite baby-faced back then), offering alternating monologues on the state of the American novel and the role of the novelist in a culture addicted to television. Wallace later wrote a letter to Don DeLillo saying the appearance had been a mistake. “I wanted to stay on my side of the screen,” he said.

In a 2011 New Yorker essay, Franzen named Wallace’s relationship to his own fame as the central battle of his adult life. He also gave voice to more than one “interpretation” of Wallace’s death that most journalists have been careful to avoid and many others probably found unseemly, that Wallace “had died of boredom and in despair about his future novels”; that his suicide “took the person away from us,” his loved ones, “and made him into a very public legend”; and that he had therefore, in hanging himself, “chosen the adulation of strangers over the love of the people closest to him.” Franzen said it might well have been “suicide as career move” — the “Kurt Cobain route.”

Although I can’t deny Franzen’s sense of the long game, I have a hard time reckoning “career advantage” as the motive in the deaths of Wallace, Cobain, Plath, Hemingway, or Van Gogh. But, then, your life rights go with you when you die. There have been at least 40 versions of Hemingway on film and television since his death, each a stand-in for our idea of the tortured artist as romantic adventurer. In The End of the Tour, Segel plays Wallace as he is now more and more remembered, a man solicitous of acclaim but made uncomfortable by attention, trying to figure out a way of living in a culture that has made him a hero but also seems designed to enhance his loneliness. Which is fitting, really, given that Wallace is now known to the public mostly as the author of that This Is Water commencement address.

A word on that speech and why I dislike it. Wallace begins with two parables: one about a pair of fish who are asked how the water is and don’t even know what water is (i.e., they don’t appreciate the wonder of the world around them), and another about an atheist who believes that God didn’t answer his prayers when he was lost in the blizzard and that he was instead saved by two Eskimo who happened to be passing by (i.e., he’s too set in his beliefs to recognize the hand of God when it saves his life). Wallace apologizes at the start for delivering “banal platitudes,” then asserts their “life or death” importance as he delivers a message about overcoming self-centeredness. It’s all breathtakingly obvious, as Wallace keeps pointing out. And then he gets to an example of one of the adult challenges this virtuous thinking will help you overcome: an unpleasant after-work trip to the grocery store. “And who are all these people in my way? And look at how repulsive most of them are, and how stupid and cowlike and dead-eyed and nonhuman they seem in the checkout line, or at how annoying and rude it is that people are talking loudly on cell phones in the middle of the line. And look at how deeply and personally unfair this is.” The horror! Perhaps I’m an outlier, but I’ve mostly enjoyed my visits to grocery stores over the years. In any event, it strikes me that there are more difficult things about adulthood than navigating the express-check-out line, and more that it demands of us than overcoming self-centeredness and reflexive sourness. What Wallace describes as a universal rite of passage into maturity seems more to me like the daily struggles of a serious depressive, which he was. To me, it’s the least interesting version of himself he ever put to the page. But an unquantifiable number of online readers, millions of YouTube viewers, and thousands of bookstore shoppers disagree. Among the more dispiriting aspects of the Wallace canonization is how much it has been built out of his suffering — the way the cult has revived, for precisely the post-therapy, post-Romantic, self-help-soaked culture Wallace described and intermittently deplored, the Romantic picture of the depressive as a kind of keen-eyed saint.

Little wars have meanwhile been going on about Wallace’s writing. He’s dominated the discourse about the novel for two decades. A short and crude version of the story might go like this. Infinite Jest appeared in 1996 and was followed the next year by Don DeLillo’s Underworld and Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon. Here were three enormous books, two by acknowledged masters and the other by their brilliant apprentice. But whereas his elders were looking backward — DeLillo to the Cold War and Pynchon to the 18th century — Wallace was looking ahead, to a time when the corporatization of North America had brought about an era of Subsidized Time, such that the calendar now measured out the Year of the Tucks Medicated Pad, the Year of the Trial-Size Dove Bar, and so forth.

It was a politically desperate vision — one of pervasive personal atomization and cynicism. If you listen to Wallace’s post–Infinite Jest radio and television interviews, he’s constantly emphasizing that he was trying to write a book about loneliness and sadness and that many of his reviewers were missing that and pointing instead to his obvious comic talent and the book’s dauntingly fractured majesty (James Wood famously described its style as “hysterical realism”).

As it turned out, it was the book’s melancholy that trickled down, detached from the structural excesses. Look at the stories collected in Granta’s “Best of Young American Novelists 2” issue of 2007, and what you see is a garden of sad tomatoes. “Is it possible that sadness can make people graceful?” the narrator of Nicole Krauss’s contribution, “My Painter,” asks. Many young writers thought the answer was “yes,” which is something Wallace himself had predicted in his 1993 essay “E Unibus Pluram,” in which he foresaw a new sincerity as the most viable direction for the generations of “anti-rebel” fiction writers raised on television’s corrosive irony. We have new problems now, and even the valence of the term “hysterical realism” has shifted, such that critic Adam Kirsch recently applied it to Joshua Cohen’s novel Book of Numbers as a compliment. Cohen had redeemed the style, he said, by fusing it to another: autofiction, in which the line between the author and the narrator is unstable, as in the books by Sheila Heti and Ben Lerner.

Of course, Wallace, too, wrote autofiction, but it was called journalism. A common reflex among readers is to divide Wallace’s fiction from his nonfiction — to treat them almost as the product of two separate brains. In fact, the projects have a lot of overlap, which has brought its own complications. When D. T. Max revealed in his 2012 biography Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story that some facts were fudged and characters made composite in the famous cruise-ship and Illinois State Fair essays, many said, “Oh, so that’s why they ran in Harper’s rather than The New Yorker. They wouldn’t pass the fact-checkers.” But as Thomas Kunkel’s new biography of Joseph Mitchell has shown, Wallace wasn’t up to anything new or all that criminal — as a nonfiction writer, he wasn’t right for The New Yorker mostly because he wasn’t a creature of anyone’s house style. What distinguishes Wallace’s journalism is not all that different from what distinguished his omnivorous, polymath fiction, which is probably one reason journalists liked it so much. Wallace called it his “giant floating eyeball” method, and if you look around, you can still see its traces everywhere, especially since the vogue for “longform” has taken hold. See, for example, the opening of Leslie Jamison’s recent essay on Sri Lanka for Afar and its echoes of Wallace’s cruise-ship essay. Here’s Wallace’s first paragraph:

I have now seen sucrose beaches and water a very bright blue. I have seen an all-red leisure suit with flared lapels. I have smelled suntan lotion spread over 2,100 pounds of hot flesh. I have been addressed as ‘Mon’ in three different nations. I have seen 500 upscale Americans dance the Electric Slide. I have seen sunsets that looked computer-enhanced. I have (very briefly) joined a conga line.

Here, in part, is Jamison’s:

I have whale-watched in the rain, or whale-sought in the rain, while our boat hit waves as tall as houses and their spray left me storm-drenched and salt-soaked and blinking against the sting. I’ve watched a Chinese woman sit beside me at the prow, clenching the railing with one hand and a plastic baggie of her own vomit with the other, undeterred, scanning the horizon for unseen blowholes … I’ve eaten mangoes sweet as candy, licked the orange stain around my mouth after sucking their pits for the last flesh.

It’s a fairly simple rhetorical trick, the comic laundry list of the traveler’s experiences, but it also calls attention to the writer’s powers of observation and establishes that the writer’s voice, rather than the subject matter, will be the star of the show. But it brings with it the risk of seducing the reader into loving the narrator and loathing the people described. Wallace called this “the Asshole Problem.” In a letter to a student who pointed out that the chubby Midwesterners in his State Fair essay seemed “animal-like,” he answered, ashamedly, “It’s death if the biggest sense the reader gets from a critical essay is that the narrator’s a very critical person, or from a comic essay that the narrator’s cruel or snooty. Hence the importance of being just as critical about oneself as one is about the stuff/people one’s being critical of.”

Reviewing Wallace’s 2012 posthumous collection of essays Both Flesh and Not, Gideon Lewis-Kraus argued that Wallace had taught the generation of journalists who came after him — writers like Jamison, Elif Batuman, John Jeremiah Sullivan, Tom Bissell, and Wells Tower — to “perform the overcoming of contempt.”

But there’s no version of this formula without contempt as an essential element. A large part of Wallace’s appeal, for me anyway, was that you could always tell that he was kind of an asshole, ever on the verge of being cruel, and not just to himself. Banishing contempt entirely may be a good way to live, but it’s another kind of death for writing. Which is one reason it’s worth remembering, as the image of Wallace as slacker saint and liberal sage hardens into Hemingwayesque concrete, that he was a Reagan voter and a Perot supporter; a jealous guy who once contemplated buying a gun to knock off a woman’s husband; and a person who put to paper both the notion that the “good thing” about 9/11 was that it brought Americans together, and that “AIDS’s gift to us lies in its loud reminder that there’s nothing casual about sex at all.” Wallace never wanted that piece republished in a collection — in fact, he wanted it forgotten. He’d probably be the last person to argue for his own sainthood.

None of these arguments would be worth rehashing if the dead man’s sentences, written in what he liked to call “U.S. English,” weren’t still so gloriously alive. There was something in him that could absorb American language in all its registers and compound it into a voice that in its every deployment said more about the country than whatever Wallace himself happened to be saying. One of the most frequently aired complaints about Wallace was that he was a show-off, that his own voice drowned out those of his characters, that there was something self-indulgent about his massive forays into antic cultural comedy. But I think he knew, having the self he had, the only thing to do with it was to put it to work, like crippled Hephaestus, hammering together his warped and magnificent books.

There will always be readers who look to novels and novelists for instruction on how to lead their lives. Wallace, foremost among his contemporaries, seems especially to attract these readers (whatever the other pleasures to be had from his books). He courted them with bromides about brains beating like hearts, literature as a salve for loneliness, and novels comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable, etc. And so it’s easy now to find online documents like this:

My name is infinitedetox and I am an addict.

Some time around May, 2004, I willfully entered into a relationship with pharmaceutical opiates. It began as a sort of experiment, quickly escalated into a recreation, and from there vectored toward present-day dependency on a straight line whose slope was gradual, but unwavering.

In December of last year it became apparent that this line would never flatten out or stabilize on its own, that it would just keep trundling on upwards, tending toward infinity given infinite time. This is when I started to get scared.

David Foster Wallace had just passed away and I decided to re-read Infinite Jest over the holidays, and something difficult to explain happened … Somehow the book — and now brace yourself for one of those clichés that Wallace seems so interested in IJ — made me want to be a better person.

I confess that this chunklet of text makes me sad, but the thing I do like about it is that in the way it vectors into the language of geometry, you can tell that here’s someone who’s internalized a little bit of the Wallace prose style.

The same could be said for The End of the Tour, assembled in part from his actual speech. On the festival circuit, the movie has garnered glowing reviews, and, whatever its complicity in softening Wallace so he’s easier to chew, it’s certainly in a league with films like The Theory of Everything and Dallas Buyers Club, essentially high-gloss true-story after-school specials for adults. Segel does a creditable impression of Wallace; you can tell he’s done his homework, watched the extant video. His innovation is to turn Wallace’s frequent wincing into the beginning of a snarl, signaling bottled rage or torment. This is the film’s version of the Asshole Problem, of Wallace’s tilting on the prickly-cuddly axis. Segel’s Wallace says he can’t stand the “enormous hiss of egos” in New York and he doesn’t want to be a guy at book parties saying, “I’m a writer! I’m a writer!” He asks, “What if I become this parody of that very thing?” Too late now.

*This article appears in the June 29, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.