On March 30, to announce the relaunch of his newly acquired streaming service Tidal, Jay Z hosted a massively tone-deaf press conference that played out like a PBS pledge drive for music’s moneyed elite. Alicia Keys quoted Nietzsche; Madonna humped a table — it was hard to recall a recent event during which pop’s one percent seemed so cringe-inducingly out of touch. The only one present who tapped into some semblance of reality was the masked Canadian EDM producer deadmau5, who stayed silent during the event and right afterward tweeted to his 3 million followers: “Yeah. That just happened. Awkward? Maybe. But I do believe in this venture! #Tidal.” You know there’s something wrong when the most self-aware person in the room is wearing giant mouse ears.

But deadmau5 (real name: Joel Thomas Zimmerman) wasn’t the only electronic-music producer — or even the only masked electronic-music producer — on that stage: Also present in that assemblage of Music’s Most Famous People 2015 were the enigmatic French robots Daft Punk and, via Skype, the omnipresent Scottish DJ Calvin Harris. If anything, this (not Tidal itself) represented a sea change in pop music: The ascent of EDM — a contentious umbrella term for electronic dance music encompassing subgenres like house and dubstep — has transformed the sound of the radio more than any other trend of the past decade, as well as become music’s biggest live draw, but it’s also shifted the way a generation of music fans thinks about celebrity. We’ve come a long way from dance music’s unsung underground heroes of the ’80s (e.g., New York’s Larry Levan or Chicago house’s Frankie Knuckles) and the faceless names associated with house music’s subsequent breakthrough. (Quick: What did the two members of C+C Music Factory look like?) But in an age when deadmau5 and Skrillex are household names, we’re moving toward a model in which studio producers and performing DJs are pop stars, too. (As well as cinematic inspirations: Eden, about the rise of French house, and We Are Your Friends, in which Zac Efron plays an aspiring DJ, are both out this summer.)

Everywhere you turn, you see evidence of this shift in favor of the producer-as-A-lister. At the Billboard Music Awards in May, Nicki Minaj was introduced alongside DJ-producer David Guetta when she performed her YOLO anthem “The Night Is Still Young” — the sort of double-billing usually doled out to a guest vocalist. Many of the tracks that Harris produces bear his name in their titles. And do not dismiss the extra-musical facets of stardom, either: Harris, at least at press time, is dating Taylor Swift.

But there’s a reason why this music, and these people, have gotten so big. (Don’t just blame molly.) The rise of mainstream EDM culture is perfectly in step with our social-media era; as any DJ will tell you, dance music is inherently populist. In his compelling new book, The Underground Is Massive: How Electronic Dance Music Conquered America, Michaelangelo Matos quotes DJ and EDM evangelist Steve Aoki. “One reason electronic music is such a successful big-group scenario is that you aren’t watching a singer,” he says. “You’re just experiencing the feeling of the music around you and being part of a larger experiential feeling.” That feeling is easy to find these days, especially in New York, now home to blessedly non-cheesy destination clubs that rival those in Europe, a scrappier spillover scene of after-hours dance parties, and massive EDM festivals like Mysteryland and Electric Zoo. (The common narrative that New York’s dance-music scene peaked somewhere between the disco and hip-hop eras no longer holds true.)

But EDM’s sense of being part of something bigger — of its relatability — depends on how you define the word us. The mainstream variant of the music obscures the history from which it springs — you can’t have Disclosure without the black and Latino queer underground that birthed house music. Today’s blockbuster EDM festivals are not only overwhelmingly white but often downright hostile to female fans (2013’s Electric Zoo was marred by a 16-year-old girl’s report of a sexual assault). On the surface, there is something new-model about the way producers like Zedd and Guetta work mostly with female vocalists, but the lack of famous female EDM DJs reinforces that tired stereotype of “female singer, male technical mastermind pulling the strings.” Even when women do rise to prominence in the dance-music world, they’re still subject to double standards about their technical prowess. “I’m tired of men who aren’t professional or even accomplished musicians continually offering to ‘help me out,’ ” underground EDM hero Grimes wrote in a widely circulated Tumblr post. “As if the fact that I’m a woman makes me incapable of using technology.”

So in 2015, the Platonic EDM star is a strange breed: part folk hero, part bottle-service big spender. This is a world, after all, in which deadmau5 — despite his aw-shucks demeanor — can command as much as $300,000 for a set in a megaclub. A 2013 New Yorker story about Las Vegas’s EDM scene featured the DJ Afrojack turning down a gargantuan contract from one nightclub in favor of a slightly less gargantuan contract at the club where he already spins. In a moment of candor, he says, “I have no idea what I’m supposed to do with all this money.” Techie, superfluously rich white dudes confused about how to spend their cash? Maybe the modern EDM hero truly is a creature of our time, a hybrid of pop stardom and Silicon Valley — someone who, like us, understands the appeal of a little hedonism. ■

One morning in May, a 67-year-old corporate executive stalked the floor of his sleek Union Square offices. He was wearing all black, including what I first thought were a pair of fingerless gloves. (They were in fact wrist braces.) “Fuck you!” he said to more than one employee lovingly, his voice a hoarse rasp owing to a bout of tongue cancer more than a decade ago. At one point, he picked up a Nerf gun, aimed it at a less-than-amused worker sitting at a desk, and pulled the trigger, sighing audibly when it turned out the gun had exhausted its barrel of foam darts.

This man, Robert Sillerman, is America’s king of electronic dance music, a title that seems both inevitable and unlikely. The producer and promoter of many of EDM’s biggest events is a lover of classic rock, a fixture in the Hamptons, a guy who just celebrated his 41st anniversary with his wife and who, when I spoke to him, had never been to an EDM show. He’s also a canny businessman and former billionaire who has capitalized on and perpetuated any number of trends in the music business over the past 40 years.

Right now, the music-business money is in EDM. In a battered industry, live events are a bright spot, with North American ticket sales at an all-time high of $6.2 billion. And EDM is perhaps the brightest one in the live-event category, with scores of new clubs, raves, and festivals coming online. Many of the biggest of them are Sillerman productions, including New York’s Electric Zoo, held on Governors Island, and Mysteryland, held on the hallowed grounds of the original Woodstock festival.

“The kids want what they want,” he told me, raising his braced hands in a “hallelujah” motion. In just three years, Sillerman has built an empire devoted to those kids, buying up promoters and events and technical talent and bundling them into a conglomerate called SFX. There are his global festivals and events and his Miami dance clubs. There’s also the celebrity-gossip site Wetpaint; Viggle, a marketing and viewer-engagement platform; and the online music store Beatport, where DJs can buy canned untz-untz-untz tracks.

But Sillerman’s ventures outside music have not quite paid off in the same way. In the mid-aughts, he put into motion expensive plans to build a huge convention center at Graceland, an Anguilla resort, and a casino on the Las Vegas Strip. Just as he was getting going, the bottom fell out of the real-estate and lending markets. Sillerman never broke ground on two of the three projects. He’s circumspect about those prior failures, calling his real-estate ventures acts of hubris.

It’s all gotten very big, very fast. There are now 700 employees answering to him, helping to put on 1,100 events this year. But this is not the first big-money synergistic jumble that Sillerman has assembled. Starting in the 1970s, he bought up radio stations and ultimately packaged them into a company called SFX (he really likes the name). That sold for $2.1 billion in 1998. Then he hoovered up local music venues, promoters, and talent agencies into a conglomerate also called SFX. He sold that company to Clear Channel for $4.4 billion in 2000. The hits kept coming. In 2006, Sillerman bought control of the Pop Idol brand for $120 million. That gave him the rights to American Idol and its numerous international spinoffs and, in conjunction with myriad other music deals, helped to make him a billionaire.

“My luck has truly been as a sociologist, doing cohort-group analysis,” he said. What Sillerman saw was music — EDM — that companies were afraid of and underinvested in because it didn’t come in a standard baker’s dozen of three-minute tracks.

That’s part of the reason that EDM took off Stateside only in the past decade or so, Sillerman said. It was social and digital media — file sharing, tweeting, Instagram, Napster, all of it — that the genre needed in order to crash the mainstream. But there are signs that EDM is finally experiencing some growing pains. There are worries that the capacity of festivals has outpaced the fan base. “The global festival market is approaching saturation as everyone fights to book the same limited pool of artists over an expanding array of events,” said a Pollstar industry report.

A potential market correction can be seen in SFX’s stock. Sillerman took the company public in October 2013. Since then, its share value has plummeted from $11.90 to around $4 over concerns that SFX is spending too much and generating too little cash. The share price got cheap enough that Sillerman has signed an agreement to buy up all the outstanding stock and take the company private at a cost of around $774 million.

Unlike those public shareholders, Sillerman is bullish about his and EDM’s future. “Eighty-three percent of our audience are millennials,” he said. “Right now, 50 percent of the world population is under 25.” He pointed out that the Netherlands, a country with one-19th the population of the United States, has as many festivals as we do. And now the leathery executive has decided to finally try out his own product. Sillerman lamented missing out on Woodstock in 1969. “I was on my way and didn’t make it!” he told me. But this year, he decided to go to Mysteryland, where he probably had a good time — not least because 75,000 EDM fans snapped up tickets. ■

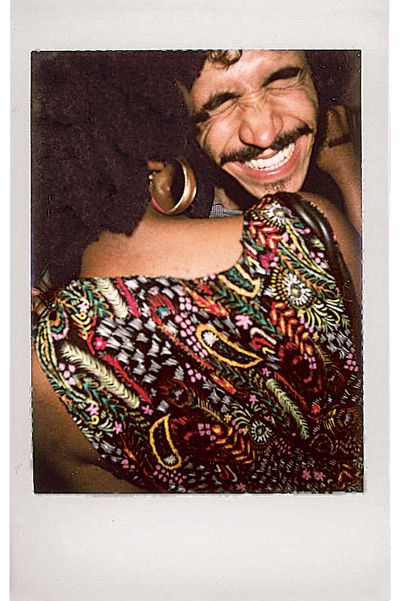

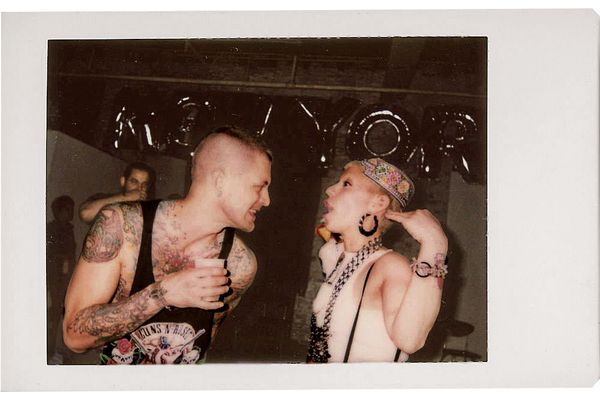

A pale morning sunlight washed over Bushwick, but it was still dark behind the doors of a dingy social club at an after-hours party in early May, where 50 or so dancers were keeping Saturday night alive. As the DJ played a throbbing record called “Ass Hypnotized,” women in tube tops and men in Mishka jerseys sucked down cigarettes and vodka while bopping to the beat. The guests shook beneath a spinning colored light and above the scuzzy floorboards, sagging under the strain of partying. It was just past 6 a.m.

As the party eventually dwindled, its organizer, Lou Gallucci, emerged from a curtained area and surveyed the scene. He’d probably wind up about $1,000 in the red for the event, owing to rival after-hours events siphoning off revelers — an increasing problem — as well as the fact that he’d shelled out for two European vinyl-only DJs and the cost of using the space. “It’s never this dead,” he said, betraying perhaps unreasonable expectations for what a party still going on a Sunday morning should look like. No matter, though. For an underground promoter in a borough with a thriving late-night dance scene, there’s always next weekend, and more late nights.

As long as New York bars and clubs close for the night at 4 a.m., there will be illegal after-hours parties. Dinky bars that shutter the windows, turn up the volume, and keep serving. Airy artist lofts occupied by financiers and models. Fleeting operations in old theaters and synagogues and on rooftops. The rise of Brooklyn’s dance-music scene and the arrival of venues like Output, Verboten, and TBA — not to mention the popularity of dance-simpatico drugs like molly — has helped incubate a cohort of people unwilling to let the party stop, and Lou Gallucci, along with other promoters like the folks behind the Cityfox, Unicorn Meat, Bushwick A/V, Resolute, and Chrome parties, is here to help. “For a couple years, I was the only game in town,” he said a few days before the Bushwick event. “Now there’s more competition. So I try to be a little different.”

Gallucci has yanked the doors off warehouses to throw parties (which he calls “afters”), been banned from Twitter for alleging the sexual predilections of celebrities, and engaged in a public war of words with the Dipset rap crew over a bungled booking. But his parties have been crucibles for New York’s underground dance-music scene, providing venues for artists like Trouble & Bass and Venus X of Ghetto Gothic.

“I know Lou’s parties are going to be grimy and have a sense of the old New York,” said Luca Venezia, who DJs as Curses. “He’s a charismatic dude with great taste. But I wouldn’t invite him to brunch with my parents.”

Seated in the early evening at the Lucky Dog bar in Williamsburg, drinking a PBR and wearing a black hoodie and battered Vans, Gallucci explained his passion for organizing illegal ragers at godforsaken hours. “I love that danger,” he said. “You don’t really know what’s going to happen. It could be the best night or the worst night. That’s what makes it romantic.”

The environments Gallucci creates are not charming. Guests are informed of addresses by mass emails and texts, creep quietly through unmarked doors abutting derelict parking lots, pay $20 cover charges to hulking bouncers who gnaw on Black & Mild cigars, and enter into industrial spaces with neon lighting and pulsing dance music. These parties are dark, smoky, and druggy. There’s always a delicious, underlying tension, a sense of lawlessness, an intuition that something could go very wrong, the knowledge that police could come streaming into the building at any moment (and, every so often, they do).

Most after-hours promoters are not as laissez-faire as Gallucci, and finding venues willing to host after-hours requires digging. “We find a place that’s going under and that has nothing to lose,” he said. For a party on Leonard Street in Tribeca, he paid a janitor for access and to clean up the mess after the guests straggled out. He said a downtown sex club charged $4,000 a night to use the premises and its hidden alley entrance. Smaller establishments might let him keep the cover charge and make money off the bar. “If I don’t go home broke,” he said, “it’s a good day.”

Gallucci, who looks like he’s in his early 30s, was born in Pennsylvania, but beyond that he won’t discuss specifics about his early life. “Keep it mysterious,” he suggested. He does say, though, that at 18, he was convicted of identity theft for forging checks and sent to boot camp as an alternative to the five-year sentence. He also says he was kicked out of the program after several months and served three and a half years in prison. After a spell in Asheville, North Carolina, Gallucci relocated to Atlanta in 1999, living in a chaotic party pad with Cole Alexander and Jared Swilley of the garage-rock band the Black Lips. “He was brilliant in a way of breaking rules,” said Alexander, “but in productive ways.” He told me, for example, that Gallucci climbed a pole to rig free internet and cable for the household.

Gallucci came to New York in 2003 to work for a small record label. Shortly after, he threw his first after-hours party, a Bushwick-rooftop shebang that featured fashion muse Alix Brown DJ-ing. The cultural shift toward dance parties — and the wider awareness of Brooklyn’s surplus of raw, event-ready spaces — was happening in earnest just as Gallucci opened the Shank, a warehouse on Bayard Street in Williamsburg, in January 2009. It became a beacon for early-morning debauchery that drew hundreds of young-and-skinnies who wanted to dance. “I thought it was crazy to do something illegal in such a big space,” said Jonathan Toubin, who used to play northern-soul 45s over the tinny sound system. “The quality of people for after-hours was insane. It wasn’t dirtballs. It was the art and music scene — it was an anomaly.”

It also couldn’t last. The building that used to house the Shank is now a CrossFit gym, but Gallucci remains undaunted. There was the warehouse that he rented under the pretense of holding a photo shoot. There were the parties in a since-closed gay theater and a space with a “men’s room” that drained onto the sidewalk. Not long ago, I went to a party of his in the basement of a Middle Eastern restaurant in the East Village. A DJ played uptempo Michael Jackson records as the cigarettes glowed. “Late-night people come and go,” said Gallucci. “They’re nine-to-fivers now.” But he’s still here, waiting for the after-party to get wild. ■

This article has been updated to show that TBA has re-opened.

*This article appears in the June 1, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.

By piotr orlov

By piotr orlov