In addition to being one of the English-speaking world’s most acclaimed cartoonists, a sought-after illustrator for everything from the Criterion Collection to McSweeney’s and the creator of some of The New Yorker’s most-beloved covers, Adrian Tomine is also an inspiration to angst-ridden teenage scribblers everywhere. The Sacramento-born artist began his career in the early 1990s by crafting terse comics vignettes, photocopying them, and stapling them into a series he called Optic Nerve. Nearly 25 years later, his style has calmed and smoothed, but he still writes and draws work with an arrestingly personal energy.

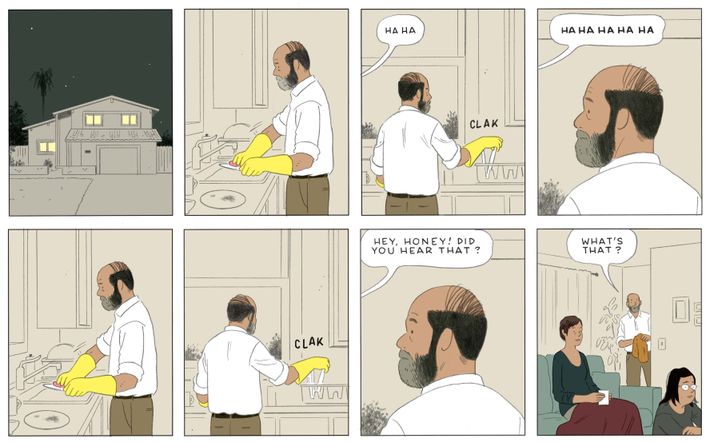

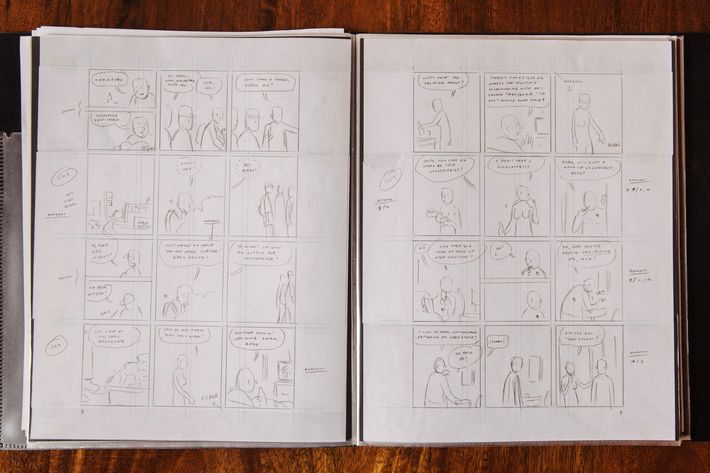

Tomine has a new collection of comics stories out today, entitled Killing and Dying. The pieces of short fiction vary wildly, from a tale about a woman who discovers she looks uncomfortably like a famous porn star (“Amber Sweet”) to an unsettling yarn about benign home invasion (“Intruders”) and the titular “Killing and Dying,” which follows a teenager’s rocky attempt at becoming a stand-up comedian. It will be Tomine’s ninth publication, and his first book of narrative fiction since his 2007 hit Shortcomings. Tomine invited us into his Brooklyn home studio, where he’d set up an exceedingly well-organized array of material that went into the new book: everything from his first sketches for its stories through to final drafts of individual panels. We talked to him about the indie-cartooning world’s changing relationship with superhero comics, the most visually striking Denny’s restaurant in Pasadena, and his attempts to stay emotionally hard-core after becoming a parent.

How often do you reread your earliest work?

Never. I don’t pick up my work at all. If it’s something that’s still in progress and I have the chance to make some edits on the material or think about the order, little things like that, I’ll keep those stories at hand and go through them. But once it exists as the book, it’s locked away in a vault, and I kind of put it behind me.

Do you at least remember and think about your work after it’s published?

Let’s put it this way: I’ve definitely met people who have a better memory of it than me. Every once in a while someone will ask me to draw a specific character, and they’ll refer to that character by name, and I’ll just think they’re referring to a friend or something. “Can you draw Alice?” And I’m like, uh, “Where is she?” I have to be reminded. It helps if they present the page to me. “This character, oh yes! I remember that now!”

I was rereading 32 Stories, the compilation of your earliest self-published comics, and was struck by something: At the beginning your style is very jagged and explosive, but by the end you seemed to have settled on the clean, rulerlike penciling style you’re known for. When did you figure out that that’s how you wanted to draw?

The big turning point for me when was the discovery of Love and Rockets and Daniel Clowes and Charles Burns. There was a number of these guys who were great cartoonists, and one thing they had in common was that they had a really clean, stylish, appealing visual style to me.

At what moment did you go, Oh wow, my drawings are starting to look like what they look like in my head?

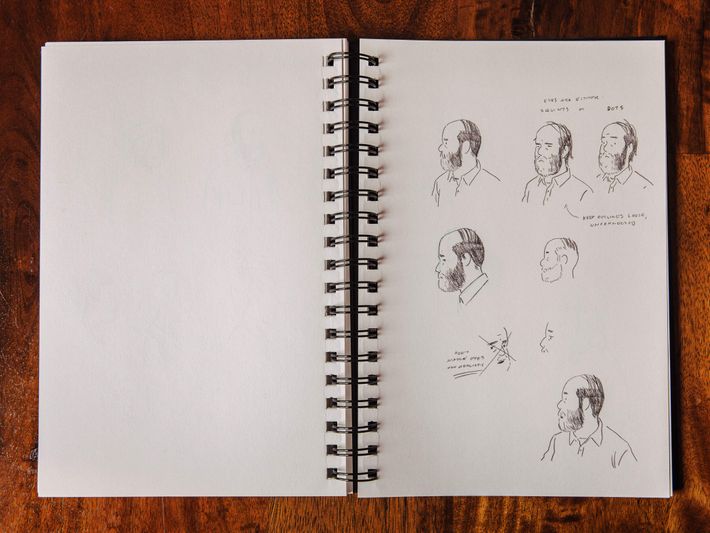

Not within the 32 Stories span. All of the art I’ve made is a struggle and in [retrospect] doesn’t look very good to me. But I would say, honestly, that the current stuff — like, Killing and Dying, to me, the artwork has a little more of an invisible quality. Which, to me, is good. I look through it and I go, Oh yeah, this is this story, or yeah, this is that character. I’m not thinking, Oh, that arm looks really out of proportion to that head, which is how I feel when I looked at the older books.

More so than your past collections, Killing and Dying has a lot of darting back and forth between giving your characters realistic eyeballs and just giving them pupil dots. How do you make the determination about which to go with?

In some cases there’s a system to it. Like, in “Amber Sweet,” it’s like [David Lynch’s] Mulholland Drive in a way: one world of reality and then an imagined world, and the art fits into that. In other cases, it’s more intuitive. Maybe I’ll have the story planned out in advance and I’ll be trying to find an art style that doesn’t look too mawkish or overwrought. So a story like “Killing and Dying,” which is a minefield of subject matter that could be handled in a sentimental or embarrassing way — the caution I took in approaching that extends to the style. Even if I kept the script exactly the same but drew it really realistically, with a lot of shading and detail, I think it would be off-putting. This subject matter is really, really dark, so if I draw everybody with every single detail on their face, it’s going to be way too upsetting. So I pull it back. If the subject matter is particularly dark, maybe a light, cartoon-y style will counterbalance a little bit.

The international cartooning world lost a giant when manga pioneer Yoshihiro Tatsumi died in March. In his last few years, you’d become something of a cultural ambassador for him in the U.S., editing translated versions of his work and doing public events with him, and you dedicated one of the stories in Killing and Dying to him. What from him did you put into that story?

I didn’t sit down and say, “I’m going to do a Tatsumi story,” or something like that. He passed away when I was working on it, so that was on my mind a lot. It wasn’t intentional, but when I finished it, I thought it reminded me of the short Tatsumi stories from the ‘60s that I really liked. That look of a bulky, loner guy moving around a city.

More generally, what have you learned from manga?

Just because of my background, it was a bigger part of my life than an average kid growing up in the West Coast in the ‘70s and ‘80s. I had relatives who would go to Japan and bring back random stuff they bought at the airport or whatever — Ultraman and Speed Racer, stuff like that. But I don’t think there’s ever been any period where I’ve been really well-versed in manga. When I was working on the Tatsumi stuff, maybe I learned a little about it through his peers and the world that he was working in at the time. But it’s hard for me when I meet a Japanese journalist and they’re like, “Who are your favorite Japanese cartoonists?” I’m not good at giving a list of names. I’m doubly limited in some ways: I can’t read Japanese, so I’m limited to what’s translated, but also my taste, in terms of subject matter and style and everything within that realm, is even more limited. That’s what prompted me to do the whole Tatsumi project: knowing there was stuff out there that really did appeal to me but maybe wasn’t being brought over to America.

What was the last movie or TV show you saw that visually inspired you?

The most recent discovery was Michael Haneke. He’s one of these guys who came along and suddenly, he’s up on that shelf for me with Kubrick and Lynch — these guys I think of as artists with a whole career that I appreciate rather than one cool movie. [Haneke’s] The White Ribbon is beautiful. Back to back, I watched three or four of his movies.

Jesus, really? His work is so grim! Doing it all at once would be devastating!

I did it after my first kid was born, and I remember being so determined to not be one of those parents who get so sensitized by becoming a parent that they can’t handle art that’s disturbing. I remember people saying, “I was such a hardass, and then I had my daughter, and then I saw a McDonald’s commercial and started crying,” or something like that. I was like, I’m not going to do that. The first DVD that we watched after we came home from the hospital with our daughter was The White Ribbon.

You’ve said the idea of a “comic book” has been sort of artistically ghettoized in the literary world, whereas the idea of a “graphic novel” is so elevated that it can be creatively stifling. What do you mean by that?

Comic books, the stapled-together magazine format, [are] stuck at comic-book stores or on newsstands. That system dictates how people are making them or producing the art now. If I want to do this interview or make sure my book’s available on Amazon or whatever, I have to put it in a hardcover format or a book format. Readers often bring a different set of criteria to the work based on the format. I’ve read some so-called “graphic novels” that were terrible, and I think, What if this was just a few issues of a comic book? That would be pretty cool. If you’re a cartoonist trying to do autobiographical or realistic comics, even if the subject matter doesn’t merit it, if you want to get it out there, it has to be packaged out like a book, with a blurb on the dust jacket, and sometimes the work suffers for it. Whereas a comic book is a humble, modest format. And it costs less.

What would it take for you to do an autobiographical graphic novel?

Not much. I’d love to do something.

Really? Almost none of your work is autobiographical so far.

I’ve never done it in a serious way. All of the autobiographical stuff has been sitcom-level introspective. That’s an idea that’s been on my list. It would be a challenge, but someone wouldn’t have to twist my arm to do that.

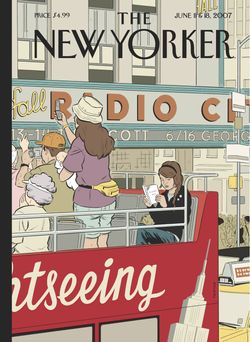

You’ve been making brilliant New Yorker covers for more than a decade. How has the process of working with the editors there changed?

It’s become a more well-oiled machine, because I’m still working basically in collaboration [with] the same two people [as] when I started: Françoise Mouly and David Remnick. After I don’t know how many covers, ten or so, we’re all familiar with each other and we all do our jobs. We’re all busy people, so we’ve gotten to the point where it’s very economical. There aren’t a lot of waves of correspondence, and I love that. The thing I hate most with illustration work is endless revisions of, “Okay, we approved it, but now we don’t like it. Go back and fix it.” There’s been enough time and experience that everybody trusts each other and everyone knows what their role is, and it’s as close to being on a team that I’ve ever felt. Athletes talk about that: They’ll have a great unspoken connection with a teammate where they know, this guy’s going to be at this place when he needs something to happen.

And is Mouly the one who reaches out to you first?

Yeah, usually. It’s not like she gives me one hard assignment and says, “Just do that.” Sometimes when I’m not in touch with her at all and I have an idea, I’ll send it over to her and she might be able to find a place in the schedule.

So what covers are ideas you’ve pitched, as opposed to ones they’ve pitched?

All of them are ideas generated by me. I mean, they might give me a topic. They’ll send you a calendar and they’ll say they need a cover that has to do with Halloween or an election that’s coming up, and you use that as your starting point, and then you’ll pitch ideas based around those parameters. But there are plenty of weeks in between where they are wide-open as well. You might see a cover that has been created long ago and they’re waiting for a time to publish it, and a lot of things get shifted because of current events.

Are there any writers or artists you admire in the world of Marvel and DC superhero comics?

No, but only because I’m not very aware of the work. There’s been a conscious effort on my part to be less critical and snobbish. Some of it gets eaten out of you [when you’re a parent] because your kid wants to listen to certain music and things like that. I wouldn’t characterize my feelings as being territorial or adversarial. I’m just not that knowledgeable about it. But especially at this time in our culture, even me saying that I’m not really knowledgeable of mainstream comics would be read as a diss. I don’t know that much about Peruvian food, but it doesn’t mean that I hate it, you know?

It’s a strange thing to be a so-called alternative cartoonist, because in the early part of my career, I was really tethered to the superhero world. For many years there weren’t even conventions [for non-superhero comics]. I’d just show up at WonderCon and hope someone takes pity on me. Cartoonists a little older than me were pissed about that, having to be a part of that world. But I’ve noticed that cartoonists younger than me are a lot more open and democratic in their taste because they weren’t forced to be a barnacle on the ship of Marvel or DC. They have their following and their fans, and they’re like, “Hey, also, the new Avengers is pretty cool, too.” The pressure is not so strong on them to be a separate identity.

The cover looks like a semi-suburban strip of stores that could be from anywhere in the U.S. Is it a drawing of a particular spot?

It’s a composite. The strip mall is taken from Oakland, near the place I used to live in Berkeley. The Denny’s is modeled really specifically on the Denny’s in Pasadena. All of the backgrounds of the freeway and all that stuff — in my mind, I was envisioning this part of Emeryville in California. But you couldn’t, like, pick a part on Google Maps that would line up with any of that. This is a California book.

Do you have a notebook next to your bed? Where do you write ideas?

I used to be more obsessive about that. I used to think these ideas were a lot more fleeting. You hear about artists pushing everything off the table to scrawl out their idea for a novel. I guess in recent years I found out I had a better memory than what I gave myself credit for. Especially with having kids, where my work time has become a lot more proscribed, it’s just like, ideas will come to me when I’m out at the playground with them, and I can’t do anything about it. It’s more of a job where I clock in at a certain time and I sit down. At least so far there haven’t been things where I’ve been tearing my hair out, going, I knew I thought of something at the playground!

How do you know when you’re done with work for the day?

Nowadays, it’s when I have to go pick up my kids from school. That’s it. The curtain drops, and that’s it. I might be mid-line and I’ve got to go. I used to accomplish the same amount over a lot more hours because I had no limitations, so I would eat my dinner in front of the TV and then go and work for a little bit, and take a nap and work a little more.

Novelist and essayist Zadie Smith blurbed the book and is in the “Special Thanks” section. Are you guys friends?

No. I’ve actually never met her.

In a CBC interview a few years back, she said she was a fan of yours.

I know, and that’s how she, unfortunately, got backed into the corner of doing a blurb on the book. My publisher heard that interview and said, “Maybe she’ll do it!” I feel bad for her. She was probably sitting somewhere and saying, “Why do I ever say anything nice about people? They just instantly descend upon me like vultures trying to profit from me.”

Why haven’t you joined Twitter?

It seems like a bad place to me.

But you joined Instagram.

I did that as a concession to promoting this book, actually. That’s fine because it doesn’t require any writing.