Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

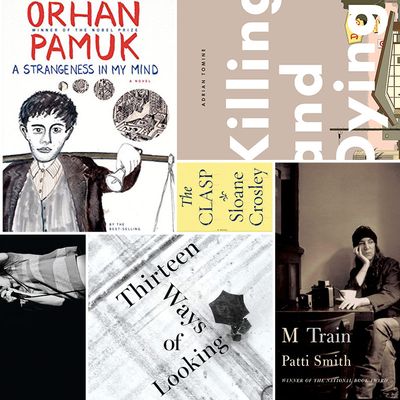

Thirteen Ways of Looking, by Colum McCann (Random House, October 13)

The author of Let the Great World Spin has spent so long illuminating history through fiction that readers might miss the real source of his power: not his heightened ventriloquism but his perfection of sentence, idea, and voice. The title novella in this quartet of contemporary stories riffs on Wallace Stevens’s famous blackbirds, the detective genre, and the surveillance state all in the fractured narrative of one heart-torn New Yorker’s dying day. Along with the other pieces, all thematically related to a random assault McCann suffered last year, it displays a rare confluence of skill, style, and moral vision.

M Train, by Patti Smith (Knopf, October 6); Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl: A Memoir, by Carrie Brownstein (Riverhead, October 11)

In bookstores filling up fast with alt-rock memoirs, two new testaments belong on the front table, if not in the pantheon. Smith’s is a sort-of-sequel to Just Kids, a revered classic that focused on her New York coming of age. M Train is gentler and weirder: Wild adventures have given way to the travels of a famous artist to Tokyo, Morocco, French Guiana, and the Reykjavík meeting of an obscure geological society, and the names dropped belong to distant heroes like Rimbaud, Schiller, Kurosawa, and the stars of her binge-watch fave, The Killing. Like Dylan’s Chronicles, it’s an eccentric bildungsroman of taste.

Brownstein’s book is more straight-ahead and DIY, not unlike both her feminist punk (in Sleater-Kinney) and her comedy (in Portlandia). The music dominates her story, especially after Olympia, Washington’s riot grrrl scene rescues her from a family straight out of Fun Home (closeted dad, anorexic mom). The surprisingly earnest account of an artist’s making and constant remaking reflects the movement Brownstein joined, which in her words replaced the elevated sense of mythos of Smith’s punk ‘70s with an aesthetic in which “the mystery was in the plainness, the starkness.”

A Strangeness in My Mind, by Orhan Pamuk, translated by Ekin Oklap (Knopf, October 20)

The Nobel Prize–winning Turkish novelist is both an exquisite formalist and a quasi-democracy’s endangered dissident. In Strangeness, he vivisects Istanbul’s last 50 years — its fascinating byways and customs, but also its corruption and heedless modernization — mostly through the eyes of Mevlut, a haplessly striving, eternally curious food peddler who’s joined a mass migration from the countryside. Forsaking much of his glimmering postmodernism (apart from some interjected narratives from a panoply of players), Pamuk comes up with an urban paean more in the mode of Balzac.

The Clasp, by Sloane Crosley (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, October 6)

The breezy New York essayist with a post-millennial undertow hasn’t radically altered her voice in transit to fiction. That’s good, because Crosley’s skittery wit and polished warmth make her first novel worthy of its meta-fictional basis, “The Necklace,” Guy de Maupassant’s short story about the fraudulence of our fetish for authenticity. Put-upon Victor, klutzy-glamorous Kezia, and endearingly vapid Nathaniel form a fraught troika of old college friends who confront their 30s via one last luminous, ridiculous adventure, a caper in the French countryside that evokes both Amélie and The Pink Panther.

The Witches: Salem, 1692, by Stacy Schiff (Little, Brown, October 27)

Early in her fluid and often (sorry) bewitching account of the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s darkest year, Schiff calls the famous witch-hunting episode “our first true-crime story.” She tells it that way, not with the fuzzy fabrications endemic to the genre but with the gift for narrative synthesis she’s brought to biographies of Cleopatra, Véra Nabokov, and others. Though Schiff doesn’t break much new factual ground, she does complicate a well-trod, often-simplified American parable. And the 2001 pardon of Salem’s last “witch” provides some much-belated closure.

Killing and Dying, by Adrian Tomine (Drawn & Quarterly, October 20)

In a collection of six very different pieces, a prominent boundary-stretcher of the genre formerly known as comics masters the graphic short story. Like their text-only cousins, these stories benefit greatly from compression, tonal variety, and allusion. In “Go Owls,” a recovering addict’s sad past and shaky prospects are legible in one or two extra lines of her face; in “Translated, from the Japanese,” a family’s tentative reunion across continents tells more in what it leaves out (like faces); and in the title story, a mother’s cancer progresses with devastating swiftness without ever being put into words.

The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government, by David Talbot (Harper, October 13)

The Salon founder’s best-known book, Brothers, found no convincing evidence of a Kennedy assassination conspiracy, and neither does this one, even though it centers on the powerful CIA director whom JFK fired and LBJ later appointed to the Warren Commission. But Talbot does find, in Dulles, a Cold War villain of realpolitik whose successes and blunders were unrivaled. As framed by Talbot, Dulles’s extra-legal interventions, coups, slush funds, and ex-Nazi collaborations were as much pro-corporate as anti-Communist, more Cheneyish than Nixonian. In other words, he’d fit right into our globalized, subcontracted, and hypersurveilled era.