In at least every extra-literary way, Garth Risk Hallberg’s highly anticipated City on Fire arrives unmistakably marked as the season’s extreme weather event. A $2 million book contract; film rights sold on the spot; 911 pages with deluxe fictional facsimiles of a DIY zine, handwritten letters, and faux-whiskey-stained typewritten manuscripts; advance author profiles in Vogue, this magazine, and who knows where else — whatever the book tells us about itself or the state of the American novel, it says a lot about what sort of story New York publishers and Hollywood think they can sell. The selling points would seem to be these: a panoramic social novel that’s also historical, and therefore not under the burden of showing us the way we live now but instead delivering a nostalgic view of the way we may like to believe we lived then; a soft focus on both the perennially fascinating ultrarich as well as two bygone bohemias (punk rock and the downtown art scene); a dizzying, schizophrenic approach to point of view, with the narrative shifting among dozens of characters, some of them very minor, every few pages; a thrillerish structure pitting sad heroes against sadistic villains; and a recurring retreat at crucial moments from realism to Disneyland logic, right down to the wicked stepmother. And then there are Hallberg’s unmistakable literary ambitions: to write an epic on the scale of Don DeLillo’s Underworld, as drenched in pop culture as Jonathan Lethem’s Fortress of Solitude, and as soaked in downtown cool as Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers.

As you can possibly tell, I’m not sold on City on Fire, but I’m curious to see if the reading public proves the enthusiasts right in their bet that this is the big novel — in its overflowing nostalgia, period-piece fetishization, and sheer physical bulk — everyone wants to read right now. As a book editor who read City on Fire on submission told me, “Christian, most people are more sentimental than you.”

For a novel so long, the plot is pretty simple, if also a bit flimsy. City on Fire is overstuffed with characters, and the lines of action uniting them fray to the point of breaking. There is a girl in a coma, Samantha, shot in Central Park on New Year’s Eve as 1976 turned to 1977. She’s an NYU freshman enmeshed with a group of punks who live in a squat on East Third Street and call themselves the Post-Humanists. Their leader is Nicky Chaos, who has usurped the remains of a punk band, Ex Post Facto, from its former front man, Billy Three-Sticks, who has retreated from music into painting and a heroin habit. Billy is actually William Hamilton-Sweeney, scion of a family that’s also been the object of a hostile takeover at the hands of his wicked stepmother, Felicia Gould, and her “demon brother,” Amory. In addition to framing William’s father for insider trading, Amory is working in league with Nicky, who is having William followed by punk spies. Nicky is also at work on a project of his own, building a bomb with explosives stolen from Samantha’s father, a fireworks maestro. A few questions mount: Will Samantha survive her coma? Who shot her? Why is the novel set in 1977? What do the tribulations of the hypercapitalist Hamilton-Sweeneys have to do with punk music? And why on earth is the novel so long?

The answer to the last question, I think, is that Hallberg has erected a few hundred pages’ worth of a historical thriller in the interest of propping up reams and reams of backstories for characters major and minor. There is at first an appealing uptown-downtown, bridge-and-tunnel (and ferry) diversity to the cast, but it yields to a pervasive melancholy. Most of the backward-looking exposition homes in on the sources of their sadness, and in the case of the major characters, these take the form of a lost parent. William Hamilton-Sweeney and his sister, Regan, lost their mother to a car accident in the early 1950s. Samantha’s mother left her and her father to run off with her yoga instructor. Samantha’s best friend, Charlie, an adopted Long Island teenager, lost his father to a heart attack, lending the family home a “forcefield of sadness.” City on Fire is billed as a 1970s punk fantasia, but the vibe of the novel is less punk than emo.

Then there’s the book’s take on punk itself. For Samantha and Charlie, sneaking into the city from Long Island to see shows on the Bowery, the music is a liberating force. There are many reverent mentions of Patti Smith, Television, the Ramones, Richard Hell and the Voidoids, the Sex Pistols, and the Clash. But Hallberg’s original contribution is the story of Ex Post Facto. We’re told the band was started as a lark by William and his friends the transvestite keyboardist Venus de Nylon, the bassist Nastanovich (if this isn’t a reference to real-life Pavement member Bob Nastanovich, the coincidence is a bit glaring), and drummer Big Mike. For them, punk is a way to pass the time between more serious artistic pursuits (in William’s case, his painting) and developing heroin habits. The band is taken over and its spirit betrayed by Nicky Chaos, a fan who offers them a practice space and turns out to be a cokehead careerist and a criminal specializing in arson, later emerging as something of a cult leader, with Samantha and Charlie joining his quasi-revolutionary cell, which lands Samantha in her coma and makes Charlie an accomplice to serial acts of arson — a far cry from the life he’d envisioned a few months earlier as a Bowie-listening high-school student resigned to someday becoming “an accountant or a podiatrist.” Charlie eventually breaks with Nicky after they set fire to a building inside which a dog is trapped. For the teenage runaway, killing an innocent animal is a step too far.

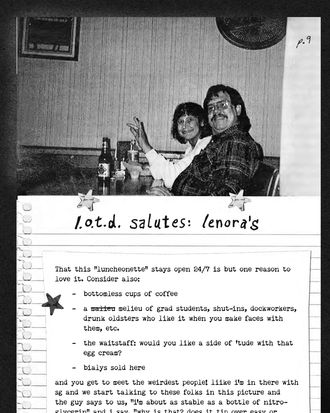

The novel’s configuration of punk as a rich kid’s hobby betrayed by violent thugs is a curious choice and less than convincing, both because it cuts against the varied class origins of actual punks (Patti Smith is the daughter of a waitress and a factory worker; Sid Vicious, a working-class high-school dropout; Richard Hell and Tom Verlaine middle-class, etc.) and because it undermines the romantic vision of punk Hallberg works to establish at the start. The rest of Hallberg’s efforts to establish a period 1970s atmosphere are even more pained. It’s hard to say that anything’s exactly anachronistic, but many of the period details ostentatiously mentioned have the effect of weakening the book’s claim to authenticity because they feel so generic and therefore secondhand. Back then, pedestrian traffic signals featured the words WALK and DON’T WALK; there were hookers on the street; it was a relatively new thing to have a color television, and there were commercials for popular processed foods like Velveeta cheese; quaaludes were available; buildings in Hell’s Kitchen looked like they’d been hit by bombs and were occupied by Hells Angels; muggings were a regular hazard. References to iconic works of the time — Taxi Driver, The French Connection, John le Carré’s novels — only serve to remind us that we’re not really there.

Centered as it is on a wealthy family’s Central Park penthouse, on the one hand, and a dingy downtown squat on the other, Hallberg’s vision of 1977 Manhattan is a ramshackle pastiche — part potboiler, part soap opera, and, in largest part, a close study of a handful of characters (not to mention an array of stock characters: an alcoholic journalist, a plucky gallery assistant, a crippled Polish cop just a few weeks from retirement who stays on the job to crack one last case), an exercise in the novel as group-therapy session. Strangely, for a story told from so many points of view, the narrative voice is uniform throughout, jaunty and knowing, peppered with $5 words and rhetorical questions, but it’s never very funny and never comes very close to the consciousness of whatever character it’s inhabiting at any given time. What the characters have in common is a pervasive ennui. Containing these people inside a thriller requires many violations of logic and resorts to cliché. Ultimately, Hallberg is trying to have it too many ways. There’s a strong tradition of social novels of New York City — from William Dean Howells’s A Hazard of New Fortunes and the novels of Edith Wharton to DeLillo and Lethem — built on near overdoses of naturalistic detail. Hallberg has tried to yoke the genre to what one character calls a “fairy tale,” but one of the virtues of fairy tales is that they’re usually only a few pages long.

*This article appears in the October 5, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.