Country music has a long and complicated history with rock. It certainly didn’t start with Steven Tyler’s flirtation with twang this year, or with Big Machine Records (the house that Taylor Swift built) rounding up over a dozen country acts to record a tribute to Mötley Crüe in 2014. It was there long before the duo Florida Georgia Line teamed up with Nickelback’s producer, and country singer Brantley Gilbert added a metal guitarist and a mohawk-sporting drummer to his lineup. Nor did it have its genesis with Dann Huff, who’s steered albums by Keith Urban and a slew of other country hitmakers and was, years before that, a member of the hair-metal outfit Giant. Or with Garth Brooks, who modeled his high-flying concert tours on the dynamism and bombast of arena rock. There’s no end to the list of other country singers, songwriters, players, producers, and stylists who’ve borrowed from various strains of rock — Southern rock, heartland rock, classic rock, modern rock, nu-metal, it goes on — to say nothing of the way that the ‘70s outlaw-country movement, with its defiant posturing, signaled to rock critics a kinship with the counterculture. For the most part, though, rock’s influence on country has been external and aesthetic in nature, a way of achieving a bigger, badder sound, or a tougher, more telegenic look.

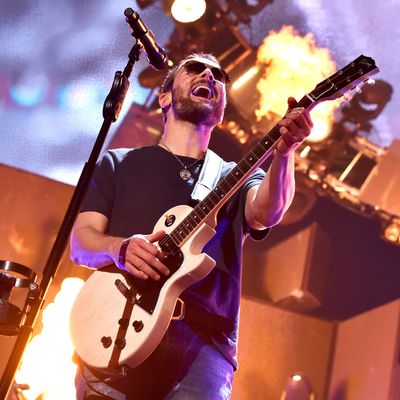

Eric Church has made these image-enhancers work for him; he’s the country star most likely to hide his eyes behind aviator shades at a televised awards gala. But he’s also taken it a lot further than that, actually embracing some of rock’s conventions, concerns, and attitudes from his position at contemporary country’s vanguard. He’s forged an identity out of fusing core values of both genres as thoroughly as just about any artist of any generation to date.

The second-biggest story in country two weeks ago — taking a backseat only to Chris Stapleton’s seemingly out-of-nowhere triple-category sweep and show-stealing Justin Timberlake duet on the CMA Awards — was that Church dropped a surprise album, Mr. Misunderstood. He even gave away tens of thousands copies — and not through the aggravating U2 method of making music magically appear in everybody’s iTunes libraries. Without warning, premium members of Church’s fan club, the Church Choir, had vinyl LPs (with CDs enclosed) shipped right to their doors. It was a huge undertaking on the part of Church’s team, partly because they had to disguise the albums, even from some retailers, as multi-artist Christmas compilations. But the real feat was that they got all that vinyl pressed in only a month, an impossibly short amount of time considering that the handful of pressing plants operating in the U.S. perpetually have many months’ worth of orders in the queue. You’d have to really, really, really want to have your ten new songs out on vinyl to go to the lengths that Church did.

Church isn’t doing interviews to promote Mr. Misunderstood (how defiant), but his longtime manager, John Peets, reports that they had to procure their own record press overseas. “We did this thing in 30 days because we had control of the press,” he tells Vulture. “We pressed in Germany, shipped to America, and direct-mailed it right over from the plant. We hid it in a distribution house. It was messy. … That’s the kind of thing you have to do.”

This vinyl obsession carries over to the songs themselves. In the second verse of the (Wilco-referencing) lead single “Mr. Misunderstood,” Church invokes record-collecting as a symbol of connoisseurship, painting a romantic picture of the way that developing one’s youthful musical taste can confer identity and individuality. This idea is one that accompanied the cultural ascendancy of the Serious Rock Album in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and lives on today in things like Record Store Day, the annual fetishization around limited-edition vinyl. “All your buddies get their rocks off on Top 40 radio / But you love your daddy’s vinyl, old time rock ‘n’ roll,” Church drawls with cool, been-there authority.

Late in the album, the subject of vinyl resurfaces as part of the cleverly deployed central conceit of “Record Year.” “Slowly plannin’ my survival / In a three-foot stack of vinyl,” Church sings, his delivery supple and subdued. “Since you had to walk outta here / I’ve been havin’ a record year.” Leaning on music to get over being left by your lover is a cherished country theme (see: Alan Jackson’s “Don’t Rock the Jukebox,” Vern Gosdin’s “Set ‘Em Up Joe”). It’s worth noting, though, that many of Church’s contemporaries probably would’ve sung about turning on the radio, not the turntable, at a time like that. (Or at any time, really, since country radio is one format that still plays the powerful role of gathering and galvanizing its audience; Brad Paisley, Thomas Rhett, and Chris Young are three among many acts who’ve worked odes to radio into their songs of late.)

The old, rockist take on popular radio listening, so expertly deconstructed by Eric Weisbard’s Top 40 Democracy, is that it’s nothing more than passive consumption of pandering playlists, especially by women. While country radio can’t afford to ignore Church’s releases these days (it was a different matter when he was building his following in the ‘00s), he counts on his fans’ whetting their appetites with singles, but also prizing his entire artistically cohesive albums. A quick scroll through comments on his Facebook page suggests he’s not wrong; lots of people, many of them possessing two X chromosomes, testify to having listened to Mr. Misunderstood three, four, six times in a row as soon as they got their hands on it, formulating and discussing their responses to the new music a mere 24 hours after its release.

Here’s a more conclusive indication that Church is right about his audience: Catch him live, and you’ll find an arena crowd just as eager to hear the deep cuts as the hits. Peets points out that “These Boots,” from Church’s 2006 debut Sinners Like Me, is the song that tends to get the biggest reaction at concerts; though never released as a single, it’s become the moment in the show when thousands of people take off one shoe, preferably a boot, and hoist it above their heads in solidarity. Besides that, Peets says that Church’s media exposure leads, at an especially high rate, to people buying entire albums rather than “cherry-picking songs.”

Over the last decade, Church has done a delicate dance with the country-music industry, participating in the system by dueting with fellow superstars— including Urban, with whom he snagged a CMA trophy the night of Stapleton’s triumph, and stadium-fillers Luke Bryan and Jason Aldean — and co-writing with Music Row pros, even as he makes a show of his independence. Church got high-concept with his previous record, The Outsiders, even veering down prog-y corridors, but this time he flaunted his freedom in the creative process, getting rolling only when inspiration struck, writing 18 songs in 20 days and recording them in marathon sessions with his producer Jay Joyce and his band. They loosened the tautness of the muscular, brooding sound he and Joyce had perfected over the course of Church’s first four albums to make room for a shaggier, mellower ebb and flow, and a bit of classic-rock noodling here and there. You could look at it as Church having a big, muse-chasing moment, à la Bruce Springsteen or Neil Young. (After all, one of the big numbers in Church’s catalogue is the nostalgic ballad “Springsteen,” and he opened the CMAs with a cover of Young’s “Are You Ready for the Country,” alongside Hank Williams Jr.). A handwritten note that Church circulated with Mr. Misunderstood drove home the spontaneity of the project, pinning its origins on a guitar that his young son dubbed “Butter Bean.” It’s clear Church is an artist who grasps the power of narrative.

He’s done his share of mythologizing, too, fleshing out a persona that’s tugged on by the theoretically opposing forces of rebellion and sentimentality, corrupting ambition and authentic passion. He’s hardly the only country performer playing out fantasies of heroism and villainy; Stapleton, the Zac Brown Band, even Carrie Underwood do it in their own ways. But Church is by far the most committed to the role. A suite of songs on his previous album — “That’s Damn Rock & Roll,” “Dark Side,” and “Devil, Devil (Prelude: Princess of Darkness)” — made countrified heavy-metal theater of it all, further amplified during his shows by a gigantic red devil rising up from the arena floor. The new album offers a fresh angle on the legend in “Mistress Named Music”; this time, Church sounds rueful and reflective, his masterful phrasing lagging wearily behind the beat, his protagonist at the mercy of an impulse that won’t let him be. That song has its counterpart in the choogling, mostly acoustic number “Holdin’ My Own,” the confession of a road dog who’s finally surrendering to the realization that his heart is at home with his wife and kids: “If the world comes knockin’ / Wonderin’ where I’ve gone / Tell ‘em I’m holdin’ my own.”

Contradictions in Church’s persona are part of what makes his music so riveting. After playing up his lone-wolf image over the years through first-person lyrics that blend autobiography, posturing, and imagination, he spins the mirror around with the song “Mr. Misunderstood.” He’s cast a misfit kid — played on the album cover and in the music video by a teenage roots-rocker sporting horn-rimmed glasses and high-top Chuck Taylors, the embodiment of the rock-geek archetype — as a sort of stand-in for listeners’ conceptions of themselves as against-the-grain outsiders. During a vamp late in the song, Church repeatedly reassures, “I understand,” sounding at that moment much more like a uniter than a divider.

For all the restlessness Church has depicted over the years with his deft lyric-writing and needling vocal attack, he’s often turned his attention to the outlier types who chose to stick around in the small towns and suburbs of their raising — the symbolic and spiritual settings of so many country songs — and depicted their struggles to live meaningful, fulfilled, rooted lives right where they are. “Give Me Back My Hometown” nailed that quandary last year, and “Round Here Buzz” is its companion piece on the new album. It’s those sorts of sympathetic gestures that have marked Church as a committed country songwriter, even as his emphasis on the album as an Art Experience have made him a country star after a rock critic’s own heart. It could be that he’s helped break down a few more of the distinctions between broad and critical taste; certainly, he’s made it feel like it means something to be an Eric Church fan.

Additional reporting by Lauretta Charlton.