On entering the principal, eponymous set from Room, reconstructed in a mall storefront next to the Landmark Theater in Los Angeles, claustrophobia quickly set in. I’m not someone to whom that feeling comes regularly, but the sensation was unmistakable: the darkness, the containment, the dizzying sense of contraction. This is the power of Lenny Abrahamson’s Room, adapted by Emma Donoghue from her novel of the same name. It wasn’t the space that made me feel claustrophobic. It was the sense memory of what I’d seen happen there.

Room itself is remarkable — and it’s always “Room,” not “the room,” a world unto itself. Abrahamson gave me a tour, explaining as we went how production designer Ethan Tobman brought to life the concept of a woman and her son imprisoned by a neighborhood man. The setup of Room is garish and eclectic, reflecting the combination of cheap materials that a man like Old Nick, their captor, would’ve seized upon to create this sort-of cage: store-brand peanut butter and white bread; cheap, shoddy soundproofing; mismatched bath, sink, and toilet, all of the sort used by people for whom color is the cheapest method of decoration.

Abrahamson and Tobman had Room built out of wooden panels that could be removed in chunks, facilitating the creative act that would be happening within. Although he shot in a variety of different camera styles, including handheld and mounted, Abrahamson and his director of photography, Danny Cohen, established one rule — rather, limitation — for themselves: The lens of the camera had to be inside Room at all times, to better reflect the confining nature of the space. The body of the camera, however, could stick of the structure via those removable panels, thereby allowing the actors some space to work. Abrahamson and Cohen shot their stars, Brie Larson and 8-year-old Jacob Tremblay, from above, below, and all around, using two cameras at all times to ensure they were capturing their child actor’s best moments.

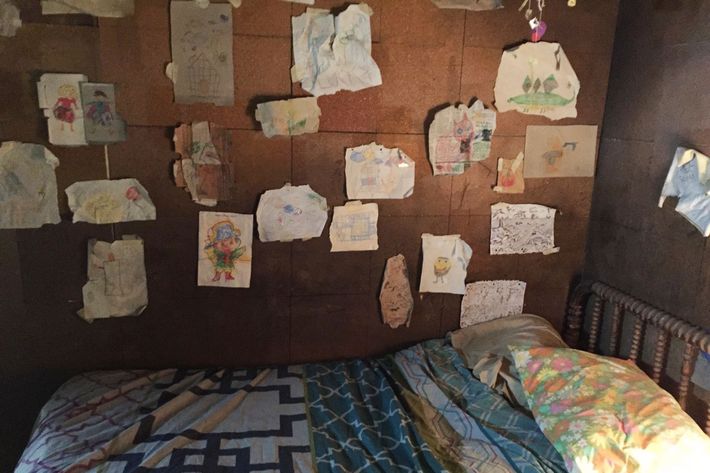

Creating a believable living environment was the other challenge facing Abrahamson, Tobman, and Cohen. Lighting was limited to just natural sources within the room, including a skylight overhead. Tobman was so thorough that he investigated the path the sun would’ve followed through that skylight had it been located in Akron, Ohio, and he faded the walls of Room accordingly. Adorning those walls were drawings and illustrations done by Larson and Tremblay, and they’re arranged to create a narrative of aging, with older drawings progressing toward newer ones. Along the wall near the door, there are marks measuring Jack’s height. Their clothes and other artifacts are strewn around. It feels like a young mother’s kitchen and a little boy’s bedroom and a grimy bathroom and kitchen all collapsed into one.

Room itself is only 150 square feet, and it welcomed 70 different crew members over the course of shooting. But what’s most remarkable about seeing it in person is realizing how effectively it conveys the actual feeling from the film, of a space lived-in and assembled painstakingly over years by a pair of prisoners trying to make a life. Toward the end of my tour, Abrahamson encouraged me to shut myself inside, and when the door closed, I genuinely felt the phenomenon of confinement.

But just a moment in there was enough. I’ve seen the movie.