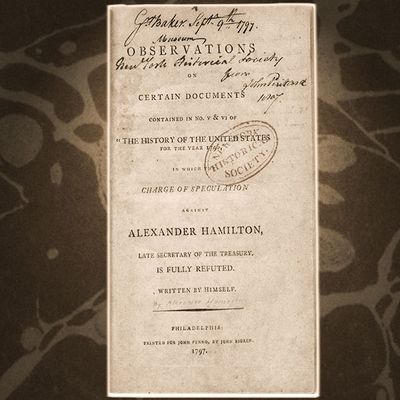

As Eliza Schuyler Hamilton begins to emerge into her own in the second act of Hamilton (the filmed version of which is now streaming on Disney+), she’s dealt a huge blow. Alexander Hamilton’s affair with Maria Reynolds, and his subsequent hush-hush payoffs to Maria’s husband James, have backfired, and rumors are beginning to circulate that Hamilton has been not only cheating on his wife but also illegally speculating with federal funds. In 1797, he took to the press himself, publishing an outraged 98 pages under the title Observations on Certain Documents Contained in No. V & VI of “The History of the United States for the Year 1796,” In Which the Charge of Speculation Against Alexander Hamilton, Late Secretary of the Treasury, is Fully Refuted. Or, as it’s commonly known, the Reynolds Pamphlet.

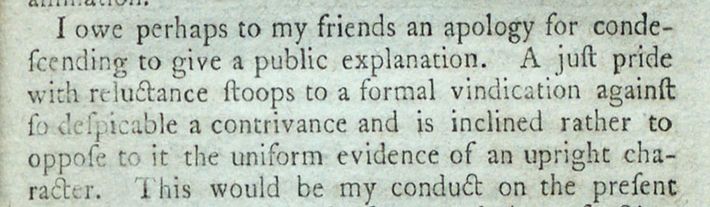

It was printed in Philadelphia, and in the window below, you can read it page by page, courtesy of the New-York Historical Society. (The Society’s putting the Pamphlet on exhibit, too, from January 15 through 29.) It’s not the easiest for modern eyes to read, not so much because of Hamilton’s writing (which is, relatively speaking, pretty brisk) but because the “long s” — that is, the typographical style of substituting a lowercase f for a lowercase s in the majority of places — is distracting. (If you find it too eye-fatiguing, there’s a modernized transcription at the National Archives site.) If you can make your way through the “extenfive and complicated mifchiefs,” what reveals itself is an extremely vigorous defense. Hamilton, as we know from Hamilton, begins by saying:

I owe perhaps to my friends an apology for condescending to give a public explanation. A just pride with reluctance stoops to a formal vindication against so despicable a contrivance and is inclined rather to oppose to it the uniform evidence of an upright character.

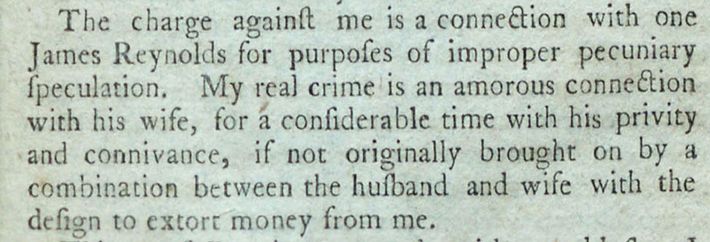

And then hangs out his dirty laundry as openly as possible.

The charge against me is a connection with one James Reynolds for purposes of improper pecuniary speculation. My real crime is an amorous connection with his wife, for a considerable time with his privity and connivance, if not originally brought on by a combination between the husband and wife with the design to extort money from me.

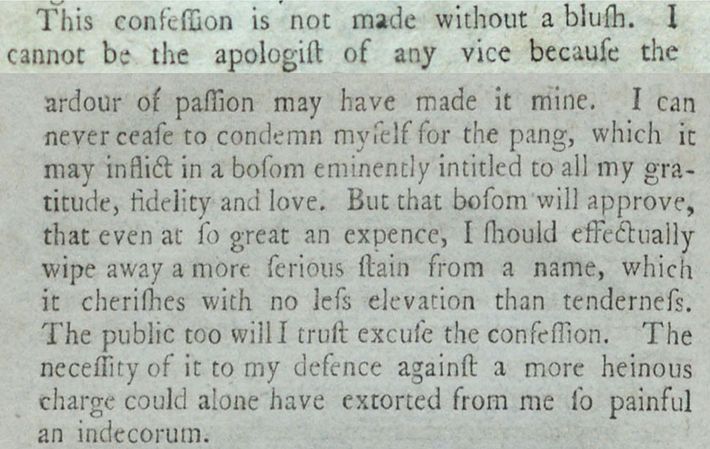

Most strikingly of all, he spends pages and pages defending his fiscal honor, and only briefly acknowledges the pain that his revelation of an affair will cause his wife.

This confession is not made without a blush. I cannot be the apologist of any vice because the ardour of passion may have made it mine. I can never cease to condemn myself for the pang, which it may inflict in a bosom eminently intitled to all my gratitude, fidelity and love. But that bosom will approve, that even at so great an expence, I should effectually wipe away a more serious stain from a name, which it cherishes with no less elevation than tenderness. The public too will I trust excuse the confession. The necessity of it to my defence against a more heinous charge could alone have extorted from me so painful an indecorum.

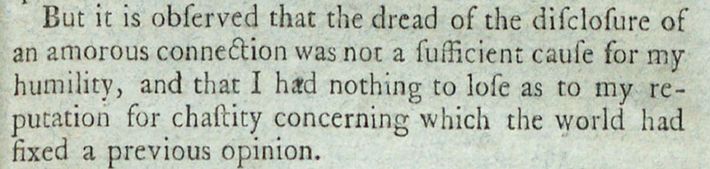

That may be because everyone already thinks he’s a dog:

But it is observed that the dread of the disclosure of an amorous connection was not a sufficient cause for my humility, and that I had nothing to lose as to my reputation for chastity concerning which the world had fixed a previous opinion …

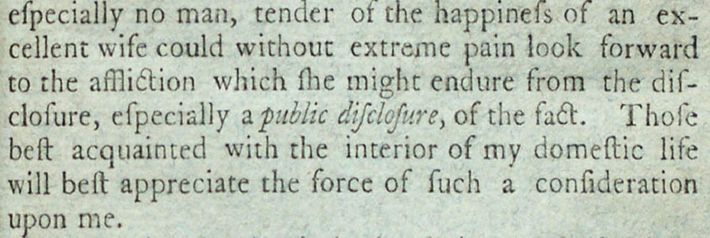

[N]o man, tender of the happiness of an excellent wife could without extreme pain look forward to the affliction which she might endure from the disclosure, especially a public disclosure, of the fact. Those best acquainted with the interior of my domestic life will best appreciate the force of such a consideration upon me.

The copy of the pamphlet we’ve shown here is one of two in the library of the New-York Historical Society, and it’s part of the collection it began assembling very early in its own history. “These are the the kinds of things we were collecting — we have literally millions of documents like this, explains Valerie Paley, the society’s chief historian. “We were founded in 1804, and a lot of the corpus of our early library holdings is from people who breathed the same air as Hamilton and wanted to make sure that early ephemera didn’t go to dust.”

“It was the first political sex scandal, and quite extraordinary that such a thing could happen in the new nation,” explains Paley, when I ask her to put the document in context. “It was as senasational then as it might be now, only we’re a little more jaded today.” Although original copies of the pamphlet are treasured, they are not quite as rare as you might think: The library at Columbia University, Hamilton’s alma mater, also has multiple copies. “It was widely publicized and printed,” she says, “and it did ruin his political career. But he thought he could preserve something of his reputation by exposing everything.”

What happened afterwards? “Ultimately Maria Reynolds filed for divorce,” she says, “and her attorney was Aaron Burr! New York was a small town.” And, as Hamilton (and Ron Chernow’s biography, on which the show is based) reveals, Eliza and Alexander’s marriage did survive. Forgiveness. Can you imagine?