“The 70s, and the scene around the Comedy Story and the The Laugh Factory, was really the birthplace of modern comedy.” That’s Showtime chief David Nevins, telling Vulture why the network decided to pick-up Jim Carrey’s series about the 1970s L.A. comedy scene, I’m Dying Up Here. Though based on William Knoedelseder’s non-fiction book of the same name, the show—which does not yet have a release date—will be fictional, following a variety of up-and-comers, some of who will explode into stardom and some of who will, well, not. Though you might see period pieces about various music scenes (i.e. Vinyl), this is a first for comedy. As a part of our week looking into NY and LA comedy, Vulture spoke with the show’s creator/executive producer Dave Flebotte about what makes that time period and location so enticing as a subject.

Can you tell me a little bit about the genesis of the project?

My agent brought me a book called I’m Dying Up Here that Jim Carrey and Michael Aguilar had optioned. I loved that scene. I dabbled in stand-up in the ‘90s and I’ve always been in love with comedy. I thought it could really be a cool period piece. You see those times with music but you don’t see it in the comedy world.

You’ve written for both comedies and dramas. What’s your goal is in terms of tone with I’m Dying Up Here?

It’s a drama. It’s a drama infused with dark comedy rather than a comedy infused with drama. Still, we wanna be funny, and we’re having fun. It was a sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll era. We lean into that and we lean into what was fun about it, but also what was the psychology that drove them to success.

Why do you think this is a good time to do this show?

No one’s really done it yet. In the past I found that if you wanted to pitch a period piece, forget it. People are scared they’re gonna cost a lot of money to dress up like that time. Now, especially with cable, they’re very open to time periods. And no one’s captured this time. I don’t want to knock the movie Punchline, but it didn’t offer an accurate depiction of what that world was like. It wasn’t how I remembered the clubs being. So, this was another way of exploring that time period in America, especially because comedy was coming up so strong. In the ‘60s we had Richard Pryor and George Carlin and this transformation that was taking place. From that, standing on the shoulders of those guys, comedy really became more personal and more interesting because it wasn’t just set up/punchline. I wanted to get in there first.

The source book is nonfiction, but the show is not about David Letterman and Jay Leno and the real people in the scene. Are key figures going to be passing through?

It’s a hybrid. The characters are a composite of different comics that I like. Of course, I’m veering way from that as I’m writing, and then when you cast the actors you veer away from your original concept even more. Then they’re just individuals that are funny.

A lot of the people we cast are stand-ups, so they already have a voice and we tailored the characters to that. I don’t want it to be so insular that it seems like the LA comedy scene was seven comics. We want it to feel fluid, people coming in and out, and we wanna have the Lettermans and the Lenos and the Pryors. You want them in that world. You want them to be essential. Maybe they’re just coming out on stage and having a little exchange. It doesn’t have to be the focus of anything. They may be tools to inspire or facilitate story, but I don’t think we have the legal right to do anything more than that.

Are you writing acts for these fictional comedians?

I did in the pilot, and that changed more than anything. When you have actors like Andrew Santino and Erik Griffin and Al Madrigal, these are established stand-ups. They do this for a living, so they elevate everything. Like with Al, it was all his. His character’s act was very specific to being Mexican-American. I can do a serviceable job, but then they bring their own inflection and their own take on it. “How about I say this after?”

When it comes to the dialogue, I can be a little bit precious, but when it comes to the stand-up, they have all the leeway in the world because they’re the pros. For me, it’s more about honing point of view and working within that point of view and that time period. Because a lot of times what happens is, we go like, Oh, that’s really funny, but in 1973, that wasn’t a phrase. Or, You wouldn’t do that to get on Carson in 1973.

So, it will go through these filters and hopefully be funny, because there’s nothing worse than watching stand-up that doesn’t sound like stand-up, just bad writing. I talked to Tom Dreesen, who was big in the ‘70s and creative consultant on the show. He helped me with the specifics of that time period. He was on Carson like sixty-something times. There was a lot of stuff like, Yeah, we wouldn’t do that, That was probably much later, and You’d never get on Carson with that material. It was all fine-tuned.

Are you setting it in a specific year?

1973. I don’t know what time of year. I know I’m writing something right now that’s specific to the fall.

It’s LA. You don’t have to worry about what time of year it is.

It’s just sunny.

Why ‘73 and not, say, ‘75 or ‘76, or even ‘81?

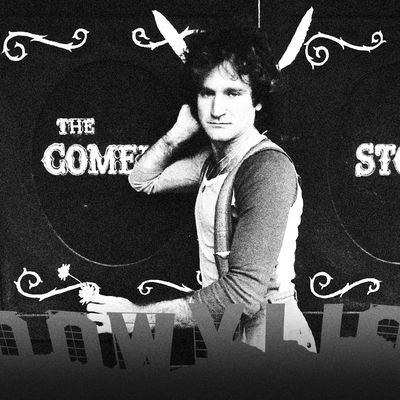

I wanted it to be like it was picking up steam. I didn’t want to be at the very beginning. But it is right when Carson mentioned The Comedy Store on his show. That is what started this flocking to Mecca, where Mitzi [Shore, the club’s owner] became the gatekeeper to Carson, which became the lottery ticket to a sitcom, a movie, any kind of success, Vegas, albums, whatever. ‘78 is when it really peaks, but it also starts to fall apart a little bit. When comics started to get successful – you have your Robin Williamses that went from zero to millions of dollars. You had drugs, like pot. Pot was very communal. Then when money came in, cocaine came in. Then it became cliques – those that were invited in and those that weren’t. Pot didn’t galvanize them in any way, as it was something that was shared. Cocaine did the opposite, as it was given judiciously to those that were in a higher circle. It started to push that family aspect apart a little bit.

Also, in ‘73 you had the beginning of Roe v. Wade, you had the end of the Vietnam War, you had Watergate. Not that we’re going to delve into all those period things, but everything was happening.

What was it about LA in the ‘70s, especially in contrast to New York?

It was Hollywood. It had that draw that New York doesn’t have – nowhere else has. This is the dream factory. This is where people come to make things happen in their careers. No one was born and raised here, so everybody’s coming for some gig, whether it’s acting, directing, writing, stand-up comedy, music. It’s a little bit of everything. I do think that at that time period, the Sunset Strip was having a moment. It was a riot house, it was rock-and-roll, it was drugs. It was much more crime-ridden than it is now, and grittier.

It’s interesting to write a world that has this juxtaposition in it – the possibility of becoming a millionaire overnight or guy with the barrel fire on Sunset Boulevard. Sunset Strip in the ‘70s has been described as everything from nirvana to pure evil. It’s a lot to play with as a writer. Carson and The Comedy Store and Rainbow [Bar and Grill] and the Whiskey [A Go Go]. You had this rock-and-roll / comedy fusion. And they did interlope. It feels really vibrant, alive, and dangerous.

There were people who came up in the ‘60s that performed in LA. at this time. How much interaction were they having with the young guys? Did Richard Pryor hang out with a struggling Jay Leno?

I know from Jim Carrey that Richard Pryor sat and talked to Jim one night for a long time. There was a respect. When Richard Pryor showed up, everybody showed up. Also, Rodney Dangerfield was very helpful to people. There was a lot of fraternization. This is where people that didn’t fit in many other places fit in. There were probably rivalries and all that stuff, but even Letterman and Leno were good friends. They used to critique each other’s acts and give notes on jokes. That exists to this day. Probably about eight months ago, we went to The Comedy Store with Jim. He hadn’t been back there in ten years. He held court outside; the comics idolized him. He was in his element.

Beyond the time period, what is it about the life of a comedian that interests you?

I’m always interested in characters. With comedians, it’s not just being funny, but what’s underneath. Comedy is literally therapy. It’s stuff that you wouldn’t tell your best friend that for some reason you’ll tell a packed house. I like that aspect of it. There’s something about the vulnerability of it, the bravery of it. That appeals to me. It all comes from places with some sort of damage. It’s interesting how they heal themselves. 15 minutes on stage is what gets them to the next 15 minutes, to the next day.

With stand-ups in the cast, have you gotten a sense about how things are similar or different nowadays?

The experience now is different but there’s a similarity underneath it all – the de facto family, the camaraderie. There was such proliferation of comics in the ‘80s. Bowling alleys were doing stand-up night. You would go and pay top dollar and it was all these crummy comics because there were just too many. After the boom ended, it distilled down to really good comics.

Now, it’s a little bit back like in the ‘70s, with some really intelligent comedians who are really funny. The Tonight Show doesn’t even do stand-up anymore, but comedians have so many more outlets for their creativity that they’re not beholden to this one ideal. They’re playing to much larger audiences, however, and that’s the difference. It’s not that they don’t have great respect for the Richard Pryors and the Carlins, but it doesn’t sound like they really relate to the generation as much as look back on it and think it was interesting.

Additional reporting by Josef Adalian.