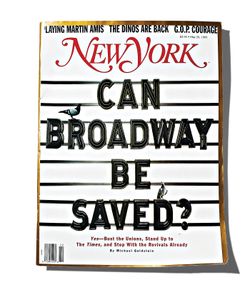

When New York took a long look at Broadway back in 1995, there was no talk of a golden age. Instead, the question on the table was ÔÇ£Can Broadway Be Saved?,ÔÇØ and you could be forgiven for thinking that the answer was no. The business was looking particularly frail, after a decade of nearly flat box-office take. Artistically, the dominant form in that decade had been the blowsy, razzle-dazzle British-import musical: Cats, The Phantom of the Opera, Les Mis├®rables, even (God help us) Starlight Express. Various factors (union featherbedding, steep rents) had driven up ticket prices, making a theater visit an occasional treat instead of a regular event.

Meanwhile, the product was pretty thin. In the 1994ÔÇô95 season, exactly two new musicals opened, one of which (Smokey JoeÔÇÖs Cafe) was really a staged revue. The theater community was demoralized, too, not least ┬¡because you could barely go a day without seeing a young male actor or costumer or set designer in the TimesÔÇÖ obituary pages, the cause of death elided with a proximate euphemism like ÔÇ£pneumococcal pneumonia.ÔÇØ

Michael Goldstein, who wrote the feature for New York, laid out a 12-step plan, suggesting (in step one) that Broadways overlords first had to acknowledge their problems. The remaining 11 points included a few ideas that, admittedly, were never going to pan out: Opening the Tony awards to Off Broadway. (It would clobber a small show to send freebies to 800 voters, a letter writer noted the following week.) Broadway needs a czar. (Who?) Serving up McTheater  that is, licensing halls across the country to produce plays on the cheap, creating competition for upper-middlebrow moviegoers. (The quality control )

But other ideas he set forth were not only workable but necessary. Absurd union work rules for stagehands and musicians were crying out to be renegotiated. Ticket sales had to be modernized ÔÇö ÔÇ£the virtual box officeÔÇØ is the phrase here, describing an order-by-phone arrangement like the 777-FILM movie-ticket system. Notably, Goldstein wrote, ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs also time for the half-price TKTS booth to hop on the info superhighway.ÔÇØ Nobody was there yet. Ticketmaster made its first online sale the next year.

He further recommended that producers one-up the scalpers by selling premium seating, as The Producers eventually did and most shows now do. The diagnosis ended with a plea for composers to embrace newer music. ÔÇ£Musical theater today is everywhere but Broadway,ÔÇØ he wrote, citing the storytelling ability of the man then known as Snoop Doggy Dogg. ÔÇ£At last,ÔÇØ Goldstein concludes, ÔÇ£Broadway could join the ÔÇÖ90s. Or at least the ÔÇÖ60s.ÔÇØ

The Aftermath

Broadway has indeed come back, and is livelier and more exciting than it has been in generations, but it did so via a route somewhat different from the one we laid out. The unions certainly werenÔÇÖt busted, but some of their most expensive work rules have been renegotiated. (A show at the Majestic Theatre, for example, was required to hire 26 musicians in the pit; now the minimum is 18.) Load-in requirements ÔÇö which had meant that getting a showÔÇÖs set and props into the theater could cost nearly $1 million ÔÇö have been tamed slightly. And, Goldstein says today, ÔÇ£One thing that I got wrong ÔÇö I said something about profit sharing, and to my knowledge thatÔÇÖs never happened. But a buddy of mine pointed out to me that theyÔÇÖve got 12 ┬¡producersÔÇÖ names above the title on some shows. ItÔÇÖs definitely not profit sharing, but almost loss sharing. You just have to get a lot of people to sign up who might not mind sharing in a $15 million bath.ÔÇØ

Most of all, though, two things happened: Tourism ÔÇö stoked by governmental action ÔÇö poured money into Times Square and its environs, and the subsequent growth of the audience widened the realm of possibilities. Amid semi-permanent fixtures like Chicago and Jersey Boys, unorthodox shows like Fun Home and The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time have run in the black. Ten new musicals were staged in the 2014ÔÇô15 season, and although the year had its share of clunkers, three of the ten were critical and commercial successes. Even movie adaptations like Bring It On: The Musical and Kinky Boots are a lot better than they need to be.

Snoop Dogg never got a Broadway revue, but Tupac Shakur did (albeit unsuccessfully) ÔÇö and, of course, hip-hopÔÇÖs vigor finally arrived in the form of Lin-Manuel Miranda, with In the Heights and Hamilton. Twenty years on, Broadway did finally find the 1990s, and has a clue about moving beyond them. Even if Cats is due back this fall.

*This article appears in the March 7, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.