The theater is dying. The theater is dead. Oh, look, it’s reviving; no, it’s dead again. It’s always been that way — yet suddenly, now it isn’t. For the first time since losing its connection to pop culture on one hand and the intellectual traditions of the stage on the other, New York theater seems to be entering a Golden Age — or let’s call it a Second Mini Sorta Golden Age With Caveats. Yes, most commercial shows lose money, schlock and watery revivals wait around every corner, and tickets cost too much. And yet, and yet: Theater is a force in New York as it was not even just a few years ago. Leave aside the fact that Broadway alone took in $1.4 billion last season and is more financially stable than it has been for decades. It’s the experience of theatergoing that has changed most dramatically. We are no longer surprised to encounter an ambitious new play, richly imagined and gorgeously executed, on Broadway, or a dozen just-as-good new ones Off Broadway, or, Off–Off, a ton of promise, possibly underfed and a little undisciplined but offering riveting new ideas about how we live. Even musicals, those lumbering dinosaurs, are once again glowing with purpose. The actors you see here have more than a little to do with it, every one delivering a performance of power and complexity this season; below, you’ll find 28 more reasons to declare this age, at the very least, Mini Sorta Golden.

Many trends in the culture had to coalesce to make this happen. To name a familiar one, Glee snuck musical theater back into youth culture, disguised as a tortured-teen soap. But the two most important changes are about the demographics of artists and the taste of audiences. Just as the Jewish play did in the 1940s, and the gay play in the ’80s, stories about race especially — and also gender, class, and other knotty subjects — are emerging as an important engine of even commercial theater. Still, no matter how good, those plays wouldn’t have any effect if audiences resisted their subject matter. Instead, miraculously, they’re embracing it.

1. Hamilton.

As George Washington sings, “The elephant is in the room,” so let’s get this out of the way: Lin-Manuel Miranda’s rainbow history lesson is the only real-world megahit that has felt like genuine theatrical art since A Chorus Line and, before that, the last golden age. Partly, that’s owed to the music, which bridges Broadway tradition and hip-hop; the cast album outsold most pop this year. Its defiantly unorthodox casting also makes it politically potent, creating a new generation of theater fans (many of whom could never have been dragged to a Broadway show before) and the stars to go with them. Has it remade the musical? It didn’t have to. It merely — merely! — exploited the full power that was already built in.

2. And Fun Home.

Miranda is hardly the only one creating theater that you’d never expect to see in a Broadway house. Jeanine Tesori and Lisa Kron’s lesbian coming-of-age musical, set partly in a funeral parlor and based on Alison Bechdel’s graphic-novel-style memoir, continues to fill nearly all its 740 seats more than a year into its run. Ten years ago, it probably would have been considered unproducible outside a 99-seat black box in Northampton.

3. But this is not just about musicals.

Stephen Karam’s The Humansmight have been an easy yes in London. But an American play that depends so much on genre mash-up and parallel storytelling and fractured conversation? It’s as unlikely to be on Broadway as — well, as Fun Home is. Yet it made the transfer last month, not because it has big stars (it doesn’t — just local greats like Reed Birney and Jayne Houdyshell) but because it was too good not to.

4. More American plays!

Really, this is an unusual moment when younger playwrights offering good (and challenging) work are getting big-time productions. Lisa D’Amour, Danai Gurira, Will Eno, and Ayad Akhtar, all of whom might have had DOWNTOWN EMINENCE stamped permanently on their foreheads not long ago, saw their plays Airline Highway, Eclipsed, The Realistic Joneses, and Disgraced make splashes (if not profits) on Broadway.

5. Especially The Flick.

Annie Baker’s Pulitzer winner found commercial success Off Broadway (when was the last time that happened?) despite a three-hour running time, pauses as long as some people’s naps, and a script whose only action sequence involves cleaning spilled soda off the floor.

6. Diverse younger playwrights.

Whatever their own backgrounds, members of the rising junior class of theater writers are more comfortable addressing race, gender, religion, and the universal problems of poor old humanity (like poverty and old age) than ever before. Consider just a few: Taylor Mac (Hir), Branden Jacobs-Jenkins (An Octoroon), Lucas Hnath (The Christians), Robert O’Hara (Bootycandy), Amy Herzog (4000 Miles), Young Jean Lee (Straight White Men), David Adjmi (Stunning), Tarell Alvin McCraney (The Brother/Sister Plays), Jordan Harrison (Marjorie Prime), and Anne Washburn (10 Out of 12).

7. Our mid-career masters lie in wait to surprise us.

Suzan-Lori Parks, Richard Nelson (whose Apple Family series is an underacknowledged classic), Paula Vogel, Tony Kushner (simply being Tony Kushner every couple of years), Lynn Nottage, and Kenneth Lonergan (mysteriously silent, but returning this month!) all remain in their collective prime.

8. And the most important musical-theater creator alive is hard at work.

At 85, Stephen Sondheim says he has at least one more show in him — a collaboration with David Ives based on two Buñuel films — and the Public says it’ll produce it whenever they’re done. Likewise, the 88-year-old John Kander, rematched (after the death of his longtime co-writer Fred Ebb) with 37-year-old Greg Pierce, just keeps going. Their Kid Victory opens this fall.

9. The artistic offspring of those masters have not been idle.

Over the past decade or so, Adam Guettel and Scott Frankel and Michael Korie and Jason Robert Brown and Michael John LaChiusa have been reimagining what a musical can be. Not always successfully, but no matter; they’re stretching the medium. Expect new work in the next year or so from all of them.

10. We have never seen people move in so many ways onstage.

The age of the Jerome Robbins–like star choreographer has ended; instead, theatrical dance has widened its scope, putting all sorts of other movement worlds in play. Just a few who have been on the boards lately: Christopher Wheeldon (An American in Paris) from ballet; Bill T. Jones (Fela!), Annie-B Parsons (Here Lies Love), and Hofesh Shechter (Fiddler on the Roof) from modern dance; Savion Glover (Shuffle Along) from tap; Sergio Trujillo (On Your Feet!) from Latin dance; and Sonya Tayeh (The Wild Party) from TV and movies.

11. Stagecraft.

The level of design we see and hear is so high it almost seems to justify the cost of putting it there.

12. Our best classic musicals keep returning in fresher ways than ever.

Broadway revivals used to be hackwork; few top directors wanted to stage them. That’s all changed. Bartlett Sher continues to find new meaning in seemingly overmined warhorses like The King and I, bringing out emotional depths many of us forgot lay within, and John Doyle puts more recent works like The Color Purple on fabulous slimming diets.

13. And our non-best classic musicals get important airings, too.

Largely unconstrained by a commercial imperative, those intrepid archive-diggers at City Center’s Encores! (and the summer Encores! Off-Center series) bring half-lost (and sometimes half-crazy) musicals back into the light, finally solving the problem of what to do with the infinite trunk of old Broadway material that’s not great but contains greatness.

14. Our divas do more.

Musicals have always had their fabulous female stars — the Ethel Mermans and Mary Martins — but were there ever so many who were as versatile as today’s? Kelli O’Hara’s clear white soprano swings from sunny delicacy to inner toughness as the role demands; Audra McDonald belts or operatizes or channels Billie Holiday; Idina Menzel regularly damages the roof of whatever theater she’s in, if not her vocal cords; and Patti LuPone can flirt or terrify at will, sometimes within the same few words.

15. The new golden age of TV is subsidizing the new golden age of theater.

Multiplatform carpetbaggers like Kristin Chenoweth, Sutton Foster, Bernadette Peters, and Laura Benanti, and Michael Cerveris, Matthew Morrison, and Jonathan Groff, sing their hearts and guts out onstage, go make a bunch of money doing something on NBC or Amazon or Netflix, then come back and perform for New Yorkers again.

16. Old ladies!

Lois Smith, who has been acting on Broadway since 1952, and most recently showed up sublimely in John and Marjorie Prime, is having a golden age of her own at 85, and she’s not the only one. Women on television may die out like dinosaurs after 40, but we’ve got Phylicia Rashad, Linda Lavin, Judith Light, and even Cicely Tyson showing up year in, year out.

17. The Producers.

Not the musical, which was fun enough but belonged to a more moribund time, but actual creative producers. In ten years at the Public, Oskar Eustis has brought an unlikely level of stellar achievement to its perpetual chaos, and also agreed to put on some weird little rap show about a former secretary of the Treasury. On the commercial side, Scott Rudin has a shockingly high batting average when it comes to finding properties at the sweet spot between highbrow brains and broad accessibility, casting them ingeniously, and then selling them so well that they almost always make money.

18. Directors who really direct.

The great new plays we’re seeing don’t always read that way on the page; they have to be brought to life with immense care and imagination. Most of the best big-ticket dramatic works are put in the hands of either Joe Mantello, a master stager of complicated and/or hyperintense drama like The Humans and Blackbird, or Sam Gold, the not-so-secret weapon who keeps Annie Baker’s shattered dialogue moving. Ivo van Hove strips down Arthur Miller, Ingmar Bergman, and David Bowie to their essentials. On the musical side, Casey Nicholaw (Aladdin, Something Rotten!) keeps delivering ebullient hits, and Thomas Kail, whose Hamilton staging manically avoids Masterpiece Theatre territory, can probably pick any project he wants for the next ten years. It’s nice that the ones who get all the work happen to be so good.

19. And women directors have cracked the glass proscenium.

Directing has been mostly a boys club for so long that we are only now beginning to see a whole generation of women getting their hands on the best material. Not yet the beneficiaries of equal opportunity, they are establishing themselves on an equal artistic footing with their male counterparts; the rest should follow. We’re talking about women like Rachel Chavkin, Anne Kauffman, Leigh Silverman, Lear deBessonet, Liesl Tommy, Rebecca Taichman.

20. Movie stars are getting more ambitious.

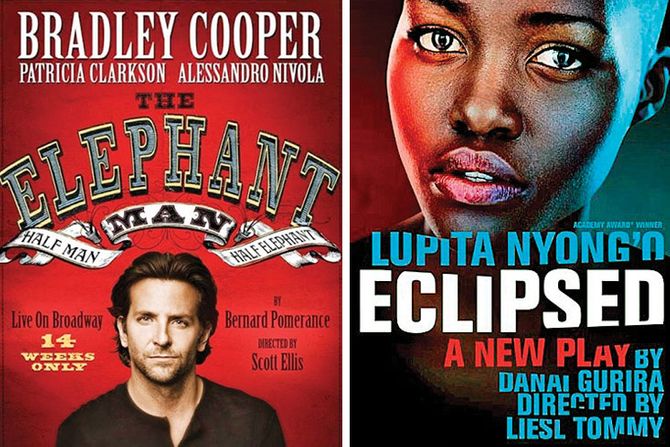

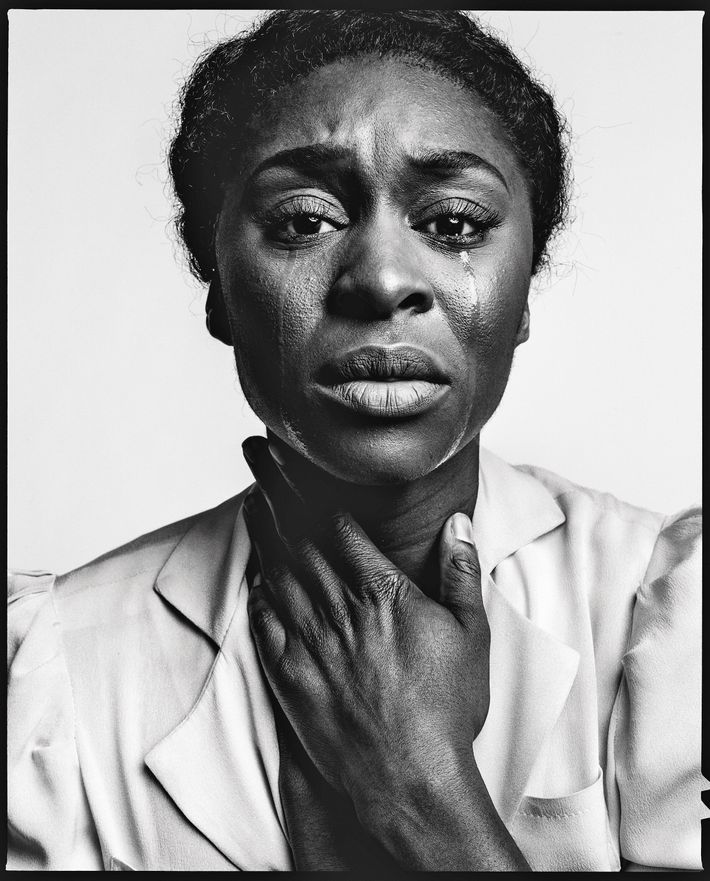

It’s no surprise that Oscar-bait actors from Saoirse Ronan to Carey Mulligan to Jeff Daniels to Bradley Cooper make regular stops on New York stages, seeking fresh challenges. The pleasant discovery is that quite a few are more than capable of holding a stage (Scarlett Johansson in Arthur Miller!) and, in many cases, choose “difficult” material that probably makes their agents flinch at the loss of income. How else to explain the excellent outings of Jake Gyllenhaal in Constellations, Keira Knightley in Thérèse Raquin, and Lupita Nyong’o in Eclipsed?

21. Star economics work.

Let’s face it: Celebrities add excitement and help lift marginal boats. We don’t want them crowding out the native species, but we don’t want them to stop coming, either. Thanks to flexible (i.e., premium) pricing, producers have figured out a formula for making the system work, with 14-to-16-week limited runs that stars can book to fit between film shoots. The star power and brevity keep the house at capacity, press is guaranteed, and the whole thing can almost be counted upon to recoup. Even China Doll.

22. Our non-stars cost a lot less and are brilliant.

New performers are stunningly well trained — sometimes too well, but there are worse problems to have. Whether it’s because college performing-arts programs are more thorough than the apprenticeships that preceded them, or because competition is driving up the talent stakes, auditions these days are full of singers with three-octave ranges who are also loose-limbed dancers and trained pianists and passable Shakespeareans and putative jugglers. Spend five minutes watching any ensemble of a Broadway musical, and you get the sense that half of them could blow away their predecessors from a generation ago.

23. Mark Rylance.

On Broadway or in Brooklyn, he’s here, and great, almost every season.

24. We are not always in deadly earnest.

Now that writers are at last offering serious perspectives on gender, race, and economic status— that’s a good thing! — a healthy bunch of ironists, updaters, condensers, and verbatimists is keeping cheekiness alive with 57 varieties of meta-textuality. Elevator Repair Service reads books aloud (Gatz); Bedlam condenses them (Sense & Sensibility). The Civilians make plays out of real-life transcripts (My Parents’ Divorce). Composer Michael Friedman (Love’s Labour’s Lost) finds quirky ways of setting existing text to music; director Alex Timbers (Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson) turns them into snarky fun.

25. We are cultural locavores.

Fresh material making its way up the culture chain has to come from somewhere. In particular, four Off Broadway (and Off–Off Broadway) institutions are proving to be brilliant incubators of new plays and voices. The Public Theater aside, in the past few years Playwrights Horizons has had an enviable track record of terrific new work (The Christians, Marjorie Prime), as have Soho Rep (An Octoroon, Blasted) and the Roundabout Underground (Bad Jews, Sons of the Prophet). And if the seats aren’t always comfortable, at least the tickets are cheap.

26. And when the tickets cost an arm and a leg, we know how to pay merely an arm.

The business model that’s making Broadway profitable again depends on theatergoers who’ll pay a fortune for premium seating. But there are also myriad ways for the rest of us to get cheap tickets: weekday last-minute rush, deals from “papering” services, discounted tickets at TKTS. We know someone who’s seen Hamilton three times without paying a dime to a broker. It can be done.

27. And sometimes we pay nothing.

You can get a lot of free theater in this city. Last year there was Theater for One, a booth in which one actor performed a top-notch short play for one attendee at a time. There’s Shakespeare in the Park — this summer, it’s The Taming of the Shrew and Troilus and Cressida. And there’s Ham4Ham, the five-minute sidewalk show, unique every time, that precedes Wednesday and Saturday evening performances of Hamilton at the Richard Rodgers. (Temporarily online-only, it’s scheduled to return live this spring.)

28. The internet is a theater all its own.

Ham4Ham became a phenomenon because of Twitter, and this entire Broadway moment owes something to social media. Forums like All That Chat, Twitter feeds like @BroadwayBlack, websites like The Interval, and everyone’s Facebook page are teeming with gossip and analysis. Suddenly, every small-town drama-club geek can connect with every other small-town drama-club geek and dis a star who hasn’t learned his lines or discuss who should revive Hello, Dolly! (it’s Bette Midler) or how amazing the camerawork was in Grease: Live. The New York theater audience, for the first time since the Rodgers and Hammerstein era, reaches to Oklahoma and beyond. And when that audience gets here, they know just what to do.

*This article appears in the March 7, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.