David Hockney’s compound, steep in the Hollywood Hills, is anonymous from the street, but once you’ve been invited through the gray gate, everything is painted in festive and surreal Hockney colors — blue and red and pink. Inside, I find Hockney slumped, asleep, in a comfy chair in the middle of his cheery skylit studio, wheezing peaceably. It’s just after noon, but Hockney is almost 79 and not, or so it seems today anyway, a particularly young 79. His work is some of the most recognizable and beloved in the world, whimsical and serious at once. It’s so familiar that it’s difficult to not think of what, for example, Los Angeles would look like uncontaminated by the way he painted it. Isn’t his L.A. the one you fantasize about living in even if you actually live there? And it’s hard to imagine the current ecstatic swagger of the L.A. art scene existing in quite the way it does without Hockney’s mythic blessing.

The next couple of years will bring about a kind of celebration and codification of Hockney’s legacy — a definitive traveling retrospective, a vivid documentary directed by Randall Wright, an impractically large Taschen monograph of his work. All this looking back must be exhausting for a man who always tried to capture how we see a moment — be it a splash of pool water or, more recently, the morning light through his window, drawn with his thumb on a program on his iPad.

Newspapers and art books are stacked around Hockney, ashes and cigarette butts at his snoozing feet. His handsome studio manager is at work on a laptop, and from somewhere, I hear the distinctive tone of a certain gay hookup app, announcing a message, and then again. Nearby, a short-sleeved curator from the Tate Britain hovers over a maquette of his museum’s temporary exhibition spaces, holding a tiny, recognizably Hockney painting — I glimpse a naked man emerging from a pool, as seen from the rear — between his fingers. This is in preparation for the retrospective, which will open there next February before traveling to the Centre Pompidou and then the Met Breuer.

Hockney, who is wearing a cozy, pilling blue cardigan and a threadbare brown cloth cap over his no-longer-bottle-blond hair, starts awake. He fumbles for a Davidoff from his pants pocket, shifting a bit in his seat, and lights it, drawing himself back into the room with his inhale, looking at me assessingly, since I had not been there when he’d dozed off. An assistant fills him in, and Hockney motions for me to sit on the chair next to his, then asks the assistant to fire up the enormous flat-screen TV along the wall. We begin to watch a video of another of his current looking-back projects, that Taschen volume, which is too large for a coffee table, more the size of a wizard’s book of spells. He still has to sign each of the 10,000 copies before its scheduled fall release.

Onscreen, a disembodied hand turns the pages steadily. Grocers, newsstands, shops. “This is 1953, ’54,” Hockney explains. “I am a student in Bradford,” the art school he went to at 16. “They’ve never been reproduced anywhere before,” he says of his juvenilia. “They all disappeared. One of the staff took them. They were very good things: He said, ‘Oh, I preserved them.’ ” Hockney shakes his head. And then we land on the famous Domestic Scene, Los Angeles 1963, of a man showering while his back is washed by another man. The scene was painted before he had ever been to California — a fantasy of what life could be.

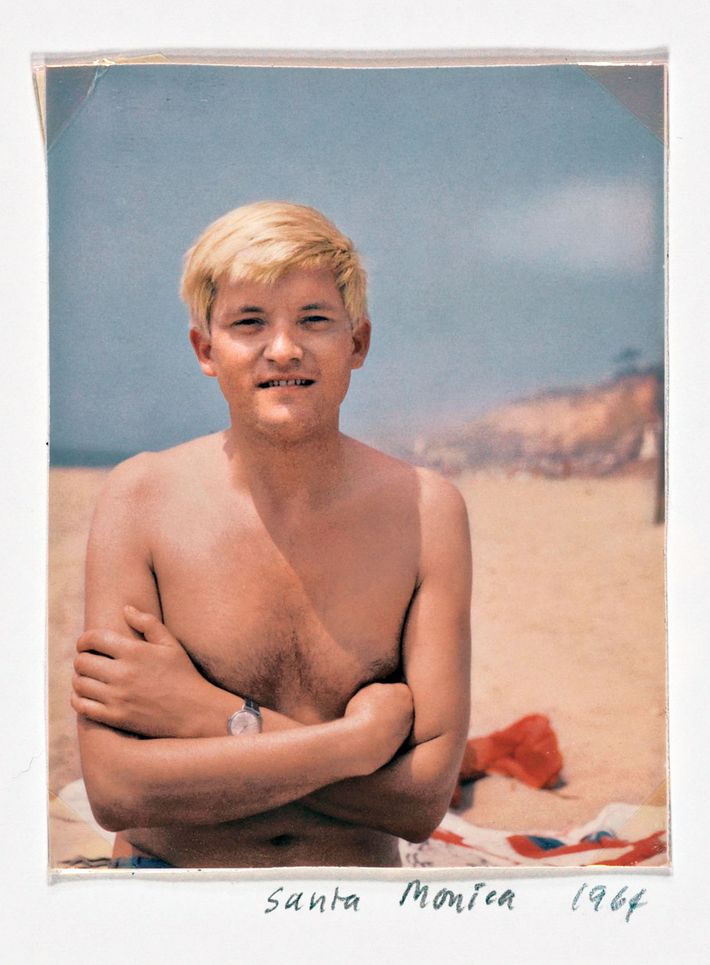

Hockney finally found his way to L.A. in 1964 with the money he made selling his take on William Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress, updated for the modern age. What he remembers most, he says, from when he first flew in was looking down from the sky at all the pools. On the ground, he found what he was looking for.

The house we’re in was built originally in the 1950s; Hockney bought it in 1981. “This was a very dark house, the ceilings were very low,” he says. “The first thing I did was put in skylights; California is about light.” The view faces toward the Valley — when he had the vegetation cut back once, you could see down to Universal Studios, but now that it’s grown in, it feels a bit like a tropical island. Down below, I glimpse the pool, quiet and private.

This is where Hockney passes almost all of his time lately. In 2005, he left L.A., then spent nearly a decade working in Yorkshire close to where he grew up, creating enormous, implausibly ravishing paintings of the local countryside, and lavish photographic experiments involving multiple cameras on a kind of rig, providing multiple perspectives at once. But he had a stroke in 2012 and found himself temporarily unable to complete a sentence (and, as he complained to the Guardian more recently, unable to get a good erection thereafter). The next year, one of his young assistants died horrifically, drinking drain cleaner after a cocaine-and-ecstasy bender. Around that time, Hockney decided it was best to come back to L.A. and sunshine.

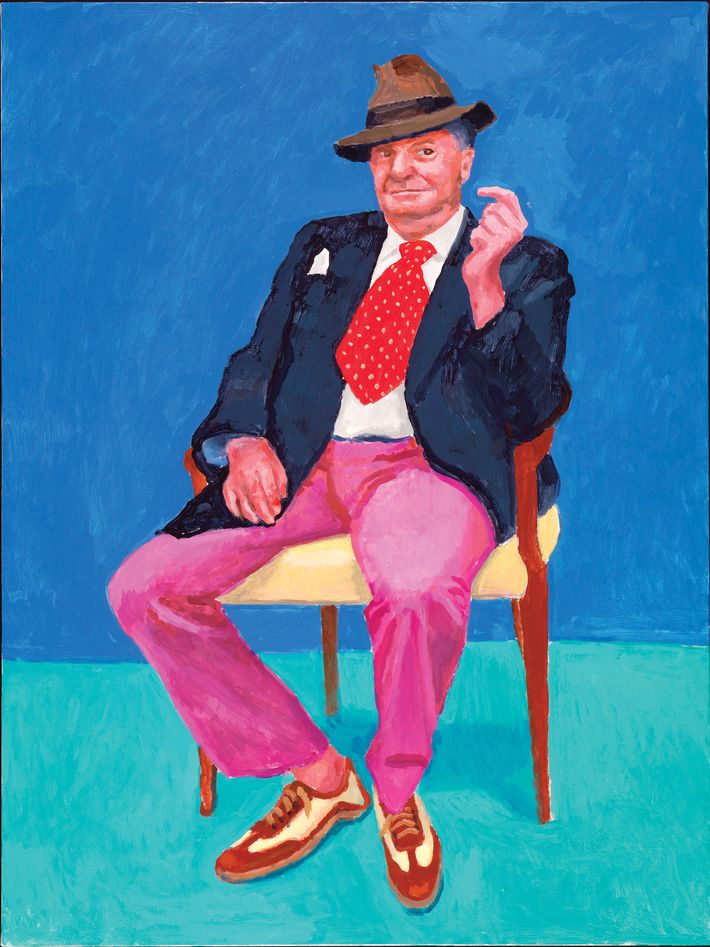

Along the studio’s longest wall are hung seven or eight of the 82 identically sized portraits he has been painting in this very room of people in his life over the past several years, which will be shown at the Royal Academy of Arts this summer. Galleys of the accompanying catalogue are on a music stand in front of him, and he flips through a copy, reading for me through the list of his friends depicted, from artists like John Baldessari to old pals like the fashion designer Celia Birtwell (who is a dotty delight in the Hockney documentary) and Hockney’s brother and sister-in-law. “They took three days each. Some of them took two days — Larry Gagosian gave me two days.” Hockney has known the megadealer since “he had a poster shop in Westwood,” he says, but has never sold with him. “He wants to sell everything,” he explains. “I don’t want to sell everything.”

The Tate curator finishes up and leaves, and we walk outside and down the stairs to the main house, which is a level down from the lush ravine he lives in, for lunch. Several of his assistants sit at a round table, with a lazy Susan stocked with sushi.

Among his concerns these days is which museum gets what paintings when he dies — the Tate and LACMA will both get their share — and in the meantime trying to cajole some of his long-standing collectors to loan works to the retrospective. He mentions to his studio manager that the Tate curator was “having a hard time borrowing paintings, actually.” He replies: “I’m not surprised. It’s for 18 months. London, Paris, New York.”

As Hockney, who stopped drinking years ago to save his pancreas, sips a near beer, we talk about his idea of bohemia, and how it has changed. “I did think I could always find like-minded people. And it was a bohemia. Now there seems to be no bohemia, doesn’t it?” Well, for one thing, gay people don’t feel different anymore, I note; we don’t feel the need for a world apart. “I think I’m different still. I came out when I was, what, 23? I was just a student at the Royal College of Art. And people said, ‘Wasn’t that good of you?’ But I said, ‘I expected to live all my life in bohemia.’ And in bohemia you could be gay. Because it didn’t matter. I didn’t expect it would close down sometime.”

We talk about his other show coming up, in Australia, which will be about technology, mostly, with a focus on the paintings he made on his iPad. Hockney has always been an early adopter: He messed around with making work using fax machines when they were current, and the documentary is full of footage he shot himself, using whatever video technology was available.

One of his assistants mentions that Hockney recently was invited in by a movie studio to try out its virtual-reality headsets, which he was skeptical about. In the video he saw, he explains, “they had a monster come toward me. And I wanted to touch it. But the only reason I wanted to touch it is because I knew it wasn’t real. But I didn’t have any hands. And I didn’t have any feet. You don’t have a body actually. Well, how will that catch on?” He goes on: “The headdresses totally isolate you. Where is shared experience going to come from? We’ve always had shared experiences. The church was a shared experience. In the 20th century, the mass media was a shared experience. Everyone went to the cinema and looked at the newspaper and things. It’s all been atomized. How do you reach the masses now?”

It’s true that Hockney has always played well to the crowd. “I always thought art was for everybody,” he tells me. “It’s like when the concert masters of Europe in the 19th century said classical music is for the educated, it’s not folk music. And Wagner said that’s not understanding the power of music. And I thought, Oh, yes, yes. And the power of cheap music, of course. I think a few people have said that: Never underestimate the power of cheap music.”

His assistants disperse, and we sit and talk over coffee. Other than his marijuana-delivery guy’s coming — Hockney smokes weed most nights, and watches a lot of Netflix — we’re uninterrupted. And as a man who is in the midst of creating an orderly sense of his past, he ends with a lesson:

“I live in the now. There is only now, isn’t there? Life is a killer. And we all get a lifetime.” He waves another Davidoff. “That’s why I smoke.”

Hockney, the documentary, opens April 22.

*This article appears in the April 18, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.