Prolificity: A short series on the methods, meaning and occasional madness of the creatively super-productive.

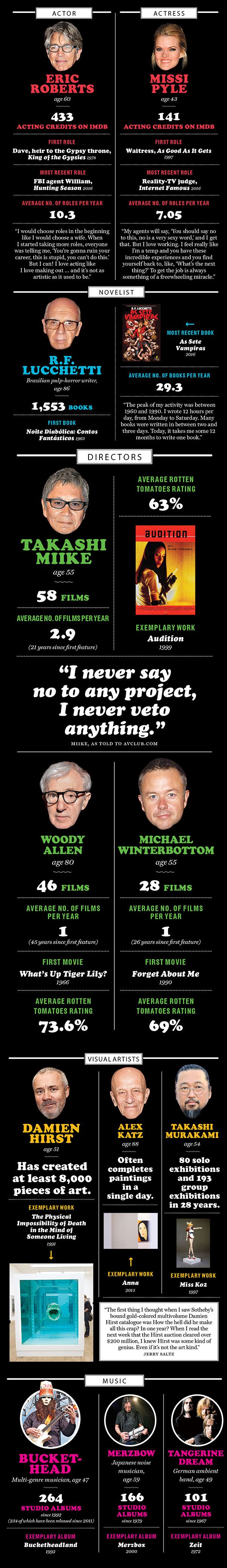

Workaholics: The Most Prolific Living Artists in Various Fields

By Jordan Larson

Our Critics Pick Their Favorite Works by Artists Who Make a Lot of Work

Art: Jasper Johns, Untitled, 2011

Jasper Johns will take a single shape, image, or motif through thousands of permutations in diverse mediums, materials, colors, and scales. Just last month, I saw this little untitled monotype at Matthew Marks Gallery. It is the only time Johns has ever allowed us to glean in the facial profile that makes up the silhouette of the central chalice the configuration of a young woman on one side and the exact same shape on the other as an old woman. For Johns, being prolific means plumbing depths. —Jerry Saltz

Movies: Michael Winterbottom, The Trip and The Trip to Italy, 2010, 2014

Just two of his 29 films, they’re not by any stretch masterpieces, but taking two gifted improvisers (Steve Coogan, Rob Brydon) of unalike temperaments on the road and letting them react to real places and people while exploring big themes is a design for staying engaged — and vital. —David Edelstein

Theater: Theresa Rebeck, The Scene, 2006

Some 20 of Theresa Rebeck’s plays have received major stagings since 1990. The one I like the most is The Scene, which starts out as social comedy but organically grows into a dark morality tale when a ditzy new girl in town turns into a homewrecker. Rebeck twists your laughs into uh-ohs. —Jesse Green

Pop: Guided by Voices, Alien Lanes, 1995

Inside his flagship band, Guided by Voices, and out, singer-guitarist Robert Pollard has released an album (or two) pretty much every year for the past 25. Alien Lanes is a great point of entry: Pollard blows through 28 tracks in just over 40 minutes, with brilliant song fragments spilling like water from a faucet. —Craig Jenkins

Books: Lydia Millet, George Bush, Dark Prince of Love: A Presidential Romance, 2000

Lydia Millet’s second novel — she’s written 14 books in the past 20 years — is narrated by an ex-convict (homicide: crystal meth, car wreck) nursing a metastasizing obsession with the 41st president. It’s one of those rare novels in which every line is funny, all the way from maximum-security women’s prison to the White House. —Christian Lorentzen

Does Writing Too Much Make You a Hack?

What we judge when we consider brilliance versus output.

By Christian Lorentzen

Talent, inspiration, hard work — some combination of these elements yields literature. Work is the simple one — anybody, we think, can work hard, can develop a work ethic. But we also believe writing shouldn’t be so easy. This is a recent disposition, dating from about the time of modernism — it’s not like anyone faults Daniel Defoe for his 500 published works, but we do instinctively do that for Isaac Asimov, who managed a similar tally. That’s because we’ve become suspicious of writers not when they work too much, but when they produce too much work. There’s a word for it: hackery. We think of hacks as turning out slick prose bereft of inspiration. As somebody once asked about John Updike, “Has the son of a bitch ever had one unpublished thought?” (The person who raised the question had recently published a thousand-page novel with a couple hundred pages of endnotes.) Hacks write so much that we stop reading them. In a culture still enamored of the romantic idea of writerly inspiration, hacks are only too sane, with their formulaic helpings of the familiar. Funny that just a few degrees further on the spectrum of the prolific are graphomaniacs, who are literally insane.

But there’s a class of prolific writers who are neither nuts nor mercenaries (as all hacks are). They are the ones apt to say things like “I’m not even faintly myself when I’m not writing,” as Saul Bellow confided in a letter to Stanley Elkin. Writers who follow their own star may be guilty of many sins and imperfections related to overproduction, but ultimately that output is a sign of health. “Sloth in writers is always a symptom of an acute inner conflict,” Cyril Connolly wrote, “especially that laziness which renders them incapable of doing the thing which they are most looking forward to.” I’d swap “often” in for “always.” We don’t live in a world where you have to choose between Updike (nearly 30 novels, some great, some not) and Renata Adler (two perfect ones), but if we did I would prefer Adler’s. Then again, Updike is a sign that inner conflict itself isn’t required for refinement: He claimed to be a one-draft writer who simply abandoned projects if he didn’t think they were working. Ultimately, the question “How much?” yields to the question “How good?” We worry about whether writers are too prolific only because numbers are easier to talk about than words and what they mean.

Writing is work, but so is reading. I’m a completist, and with most writers you can read the work of several decades in a month or two. Yet reading all of some writers would take a lifetime in itself. “We may as well get this one over with first: You’re frequently charged with producing too much.” That’s the opening question of the 1978 Paris Review interview with Joyce Carol Oates. “I really don’t know what to say,” Oates replied. “I note and can to some extent sympathize with the objurgatory tone of certain critics, who feel that I write too much because, quite wrongly, they believe they ought to have read most of my books before attempting to criticize a recently published one.”

She’s right! Though I’ve read many of Oates’s stories and essays in magazines (and once joined a pub-quiz team called Joyce Carol Overdrive), I’ve never read one of her books. Would they suck me into an Oatesian vortex from which I would only emerge decades later? I doubt it, but something of the kind happens to readers of Georges Simenon, who wrote nearly 200 novels, legendarily at a clip of 60 to 80 pages a day. Like Oates, who as an undergraduate at Syracuse was said to finish one piece of fiction and immediately start another on the next page, Simenon wrote both literary novels and genre books; more than 550 million copies of his books saw print, making him a millionaire many times over. Stephen King, many of whose 54 novels are much fatter than anything Simenon wrote, has an estimated net worth of $400 million.

If writing made everyone who could do it rich, would all writers write as many books as they could? Perhaps. The rumor has long dogged Charles Dickens that his novels were so long because he was paid by the word, but in fact his contracts were tied to sales. And anyway, there are other incentives: competition with friends, enemies, heroes, and your own past achievements; the race against death and the urge to erect monuments to yourself for posterity. On the other hand, neither money nor fame nor the prospect of posthumous glory has kept great writers from going silent. Rimbaud gave up poetry at 20 and became a gunrunner. How J. D. Salinger spent his last five decades is still the subject of rumor. The last of Fran Lebowitz’s four books appeared in 1994, but she has persisted by talking. She doesn’t have to write for the city to love her. And of course the best way to hide from the world the fact that you aren’t a genius is never to write a damn thing.

Who Cares If Woody Allen Never Leaves His Comfort Zone?

He writes and directs a new film every year.

By David Edelstein

Woody Allen has made an astounding number of movies, nearly 50 over 50 years. Few of them can be called “throwaways” — though there’s no evidence that any of them have sheared off pieces of his soul in the throes of creation, either. Although he often speaks about his general state of misery (it’s a shtick at this point), he has succeeded as few artists have in creating a comfort zone in which to work and live.

This was not a casual process. Despite being a public figure — the epicenter of Manhattan cool in the ’70s and ’80s — he labored to build a near-impregnable fortress of privacy, pierced only once. But if a notorious scandal in the early ’90s did incalculable damage to his reputation, it didn’t change his way of working or result in public hand-wringing. A poster boy for neurotic Jews, he seems anything but neurotic. Allen jumps from film to film with no apparent breaks for introspection. He is undoubtedly phobic, but if you have enough money and a system in place, phobias like his can screen out distractions and make for an even higher level of functioning. (I can’t comment on the scandal — or the repeated public challenges of his estranged son, Ronan Farrow, to brand Allen as a child molester — because I do not know the truth and neither do you.)

Can a comfort zone be dangerous for an artist? Sure. Allen’s films suffer from his life in a hermetically sealed bubble. The man who gave us the Orgasmatron in Sleeper and a boisterous battalion of sperm in Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex speaks of today’s raunchy comedies with prudish indifference: He won’t deign even to watch them. Nor has he plunged inward in the manner of Woody 2.0, Charlie Kaufman. He primarily creates trim parables that dramatize the fundamental injustice of the universe, writing and shooting them quickly, one a year.

The latest films — Magic in the Moonlight, Blue Jasmine, and Irrational Man — are heavy-handed in announcing their themes but made with a rare fluency. He makes remarkably smooth stilted movies. He prefers simple setups and long takes to anything that requires montage. He gives us a rare chance to see A-list actors plain, unmediated by agents and image brokers. We can object to some of those works — I thought Blue Jasmine played like A Streetcar Named Desire if Tennessee Williams had loathed instead of loved Blanche DuBois — but by the time we’ve hashed out our feelings, Woody Allen has made another film. He will likely die in a director’s chair and for that tenacity deserves a measure of respect.

The Prolific Brain

Why do some artists produce so much?

By Drake Baer

Some people make an insane amount of stuff. The most prolific painter of all time is Pablo Picasso, who created more than 13,000 paintings and drawings, plus thousands upon thousands of prints, sculptures, engravings, and book illustrations. Isaac Asimov authored and edited some 500 books in his lifetime. Frank Zappa churned out more than 60 albums. Yet science is only starting to understand what makes the hyperprolific different from the merely productive.

It may be that the megaproductive exhibit what psychologist John Gartner calls a hypomanic temperament, which means they are low on regulation and high on drive. “Because their minds are working so quickly, they have a lot of ideas,” says Gartner, author of The Hypomanic Edge: The Link Between (a Little) Craziness and (a Lot of) Success in America. He also notes that hypomaniacs are “charismatic at a distance, but wear on people.” They also need just four to six hours of sleep at night.

Scott Barry Kaufman, scientific director of the Imagination Institute at the University of Pennsylvania, says that the most sustainably creative people are able to flexibly engage and disengage the brain’s “executive control” and “default mode” networks. “People who keep trying to accomplish things without it coming from a deep place from within tend to be effective but not necessarily creative,” Kaufman explains of the former mode. “And people withdrawn in their default-mode network daydream all day, but they don’t put things in action.” Wildly creative people don’t get stuck in either mode. They’re passionate and they produce — over and over.

*A version of this article appears in the June 27, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.