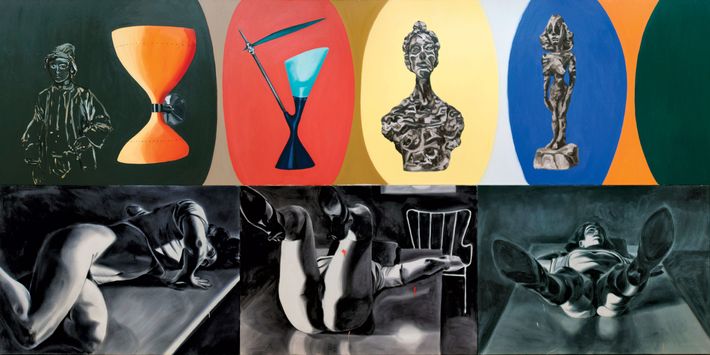

“These are unrehearsed comments,” David Salle warns me, or maybe himself, as we pause in front of one of his paintings, Fooling With Your Hair, from 31 years ago. We’re walking through a show of his early work, along with that of two contemporaries and fellow Hamptonians, Ross Bleckner and Eric Fischl, called “Unfinished Business,” at the Parrish Art Museum in Southampton. Salle is attempting, for my benefit, to push himself into a kind of reverie about his old work, but his cautiousness over the performance keeps getting in the way. (He’s better at ginning up appreciation for Bleckner and Fischl.) Fooling is a high-style Salle collage of seemingly disparate images, including several mid-century-modern lighting fixtures he tells me he copied from a book his friend Philip Johnson had given him and three possibly anesthetized women in positions of ghoulish sexual presentation on what looked to me like coroners’ examination tables. Critics categorized what he did as postmodern, and Salle, who wore his hair in a matador’s ponytail at the time, was a charismatic figure in the art scene, celebrated, and resented.

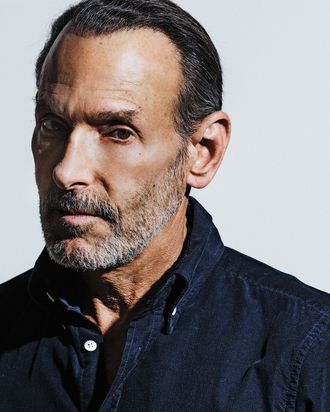

It’s a late-August Thursday — a flawless, getting-your-money’s-worth day in the income-inequality Elysium of the East End —and he’d ferried me to the museum in his purring dark Audi. Salle is trim and tanned and in flip-flops, his shirt carelessly frayed at the collar. He not only does not look his age, which is 63, but he doesn’t quite look of this current age either: There is something of the exiled aristocrat about the artist (Salle is a name his grandfather made up when they emigrated from Russia, but they were Jews, not Romanovs). His paintings have a similar sense of remove.

“Unfinished Business” is an exhibit of work from the ’70s and ’80s, when swagger returned to the city’s art world, after a period of obdurate self-criticism about making money. Salle’s generation, which included Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jeff Koons, and Julian Schnabel (Salle’s famous rival at the time), as well as the virtuoso dealers Mary Boone and Larry Gagosian (Salle has shown with both, though he’s now at Skarstedt), revived an older tradition of artist as, if not entertainer, exactly, then celebrity, man of success. A 1987 profile of Salle in The New York Times Magazine quoted Robert Mapplethorpe on the painter’s Tribeca home: “It looks like the loft of someone who made his money fast.” Fame had come quickly, too, and reputation, though each of those ebbed and flowed with the art world’s fashions and fascinations. But long after Salle was new, his work, with its standoffish sense of wonderment, has given him a very good life.

Despite his warning about the off-the-cuff nature of his remarks, Salle has never been shy about granting interviews. Janet Malcolm, in a 1994 profile in The New Yorker (which has become, in certain circles, nearly as famous as its subject), called him a “kind of interview addict” who “cultivates the public persona, but with the detachment of someone working in someone else’s garden.” And yet he’s hesitant and layered and allergic to sound bites. We are standing in front of Trucks Bring Things, from 1984, its consumerist ardency tarted up with a lit yellow lightbulb. “I can do this for someone else’s work — but what is it that it’s doing? It’s doing something. What is it? It seems so … so what … fill in the blank.” He pauses, assessing. “It holds up.”

Salle told Malcolm that being interviewed was “a lazy person’s form of writing.” But in the decades since, he seems to have put in the work: More important to Salle than the Parrish show is his new book, How to See, a trenchant and light-on-its-feet collection of critical essays and less-targeted musings about art, artists, fame, and, if you read it closely enough, what it’s like to have been David Salle for all these years. (Much of it appeared in Town & Country, where another creature of similar-vintage cultural renown, Jay McInerney, is the wine critic.) His pieces on Jack Goldstein, Mike Kelley, and John Baldessari are particularly well observed. Even his careful takedown of Frank Stella — whom he says ran out of good ideas at some point — is, like the rest of the book, rooted in generosity, or perhaps just good manners. “I don’t take it back. I took such pains to say what a great champion Frank is. And all great champions fall.”

I suggest that maybe Stella was victimized by his long life. Salle agrees. “That is the subtext.” He begins to get philosophical. “Art is long, life is long. And yet there are moments when it burns white-hot and moments when it doesn’t,” he says. “And they might look entirely different in 30 years.”

On our way out of the Parrish, we stop by a gallery filled with the work of Fairfield Porter, who died in 1975 at age 68. Porter was something of an aesthetic traditionalist and not especially well known, but he is a particular inspiration for Salle because of how he wrote about art. “It was a time when the great seductive arguer Clement Greenberg” — the mid-century critic for The Nation and Commentary—“determined the terms of the conversation,” Salle says. And since Salle has been frustrated with how art has been written about for his entire career — and not just because he was often derided by arbiters like Hilton Kramer and Robert Hughes — he took note when he read Porter’s journal (“I realized talking to Clem that my opinions are as good as his,” Salle recites off the top of his head), which liberated him to write criticism.

After the Parrish, we stop at his favorite farm stand, where they know him — in a reminder of how the Hamptons can be like a peculiar small town, he just signs for the organic produce — on the way home to his impeccably renovated old barn. His sleek and friendly five-year-old dog, Dagmar, bounds about. (“I know, I missed you too, hi, hi, I know, I know …”) As he’s making us lunch — locally produced mozzarella and tomatoes, and perfectly crisp bread in a paper sleeve — a big chef’s knife slips from Salle’s hand, nearly impaling his naked foot. He doesn’t really react.

We eat outside, under a loggia overlooking the pool, drinking mineral water. The conversation turns to how one survives as an artist. He went bankrupt early on, but thanks to the support of Johnson’s partner, David Whitney, among others — “You still need someone to go along with the gag” — he set on the journey here. We’re periodically interrupted by planes landing at the East Hampton airport, buzzing like great lawn mowers.

He retrieves his laptop and reads to me, from the memoir he’s working on, a chapter about his friendship with the haughty New Yorker writer George W.S. Trow, who wrote the book Within the Context of No Context. He tells me that one of the advantages of doing something that everyone has an opinion about, whether good or bad, is that he’s met a lot of interesting people — for example, he bought this house from his friend the writer Richard Price. He looks out at the crêpe myrtles in prosperous pink bloom. “I’m older now. When I was young, I would never tell anecdotes,” he says. “I thought they were irrelevant. But it seems like all anyone wants to hear.”

*This article appears in the September 5, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.