Here, eight awards-season hopefuls share their biggest onscreen challenges.

Matthew McConaughey in Gold

The scene: McConaughey plays scrappy mining businessman Kenny Wells, who’s finally struck pay dirt. His company attracts the interest of Wall Street investors who want to buy him out. In this scene, he has to make his choice.

“When the scene begins, it’s obvious that Kenny’s just heard that these Wall Street guys want to buy him out. He looks at the contract: ‘Where’s my name? You want me to be a minority partner?’ So I enter hot. I’m pacing back and forth like a caged lion in that room. The conflict is immediately apparent, and Kenny’s trying to figure out what to do. The way I was looking at it, he’s got the excitement of being offered $300 million, the fact his partner Mike Acosta isn’t there with him, and then this deal that goes against his principles — so he’s on fire.

It’s not a scene I could’ve done 20 times. I would’ve gotten tired. So Kenny’s thinking about all that, and when he’s pacing, I came up with that line where he bends over and says, ‘Are you gonna fuck me in the ass?’ I took it from a story I’d heard about the producer Dino De Laurentiis. I don’t know if it’s true, but I’d heard he had the rights to Silence of the Lambs and he went to a studio for a meeting and they said, ‘We really love these books, and we want to option them, and here’s our offer.’ And Dino just listened nicely and looked at the offer, stood up, dropped his pants, and said what I improvised in that moment. That was Kenny’s way of telling these silky Wall Street guys who’ve had their names on things that he wasn’t letting them take his name off his company. He was keeping a legacy alive.

We didn’t really plan that scene out or have a bunch of rehearsals. We did it once, and it worked, but then Corey Stoll, who plays one of the Wall Street guys, had an idea for the pacing of it. In the second take, I think it was, Corey pours me a drink — a very smart thing to do. So he’s holding this drink out, and it’s like, Don’t eat the apple, Kenny! Don’t do it! The audience isn’t sure which way Kenny is going to go. Is he going to take the money or stay pure? And I’m thinking, Should I slap this drink out of his hand? It creates such a wonderful interruption in this scene that’s supposed to be wild. Then instead of slapping the drink away, Kenny takes it and gulps it down — not because he’s betraying himself but because he’s gearing up for what he’s about to do. That’s when Kenny tells Corey’s character — he looks him in the eye and basically says, ‘I’ll kill you before I sell that company, my father’s hands built that company,’ and he walks out. When Kenny says, ‘My day! My day!’ as he’s leaving, that’s something I threw in, too. The whole scene is really well written, the dynamic is clear, the conflict is clear, and the choice is clear, and it shows you Kenny’s almost-childlike purity. He’s different than anybody else I’ve ever played.”

Janelle Monáe in Hidden Figures

The scene: Hidden Figures is the story of three groundbreaking black women who worked as NASA engineers in the 1960s. In this scene, Monáe’s character, Mary Jackson, has to petition a reluctant judge to allow her to take the advanced classes she needs at an all-white school.

“Actually, I had to audition with this scene. This was the scene that the director wanted me to have nailed. He wanted me to come in already prepared. When I read that script, all I kept thinking was, This is a dream role. Mary Jackson wanted justice for herself and her peers. I had a personal responsibility to her, to honor her, so I took it very seriously. I was thinking about all the women like my grandmother and all the women who opened up doors for me, especially during that era. I was thinking of them and how I had to be very smart and very particular about my language. Because Janelle Monáe during that time probably would have worded things differently. We have freedom of speech now, but back then those ladies didn’t. Their sisters and brothers were being lynched because of the way they looked at white people, the way they talked to white people. So I had to be very strategic about how I was playing Mary. It was really a tightrope in that courtroom. But she prevailed in the end.

For me, coming from the music side of things, I wanted to come into the music industry and redefine what it meant to be an African-American female recording artist. I wanted to redefine what it meant to be sexy and to not play to any stereotypical gender roles. So I brought that to [this character], because I felt like I had made some of the same choices that she would have made during that era, and I felt like we were absolutely kindred spirits. I just felt the connection to her instantly. I used that as fuel as I was preparing for this role. And because I had to know this scene backwards and frontwards, I was actually the most relaxed shooting this scene. For me, I got the opportunity to really play it, to play around and to allow inspiration and the way somebody may have looked at me to give me another way of saying certain things. I remember doing two takes and [Theodore Melfi, the director] saying, ‘We have the base. We have what we need. Now let’s just play.’ I was like, ‘Really?’ I was so shocked. I was like, ‘Are you serious?’ He was like, ‘Yeah, we have it. That was great. Play it this way now.’

[Frank Hoyt Taylor, who plays the judge] was a sweetheart, but when I met him, he was very much in character. He gave me a lot to work off. I was able to finally be face-to-face with my enemy. But afterward, he shook my hand, and I think we may have even shed a tear together, because that scene was very emotional for everyone. When the camera stopped rolling, everybody was in tears. I remember turning around and all the hair and makeup, the DPs, I remember them coming up to me and saying, ‘We shoot a lot of scenes, but this was special.’ [Frank] was such a sweetheart, and he hugged me and said, ‘Congratulations. You’re going to touch hearts around the world.’ I said, ‘I hope so.’ I really hope that Mary’s spirit lives on and people are inspired by her.”

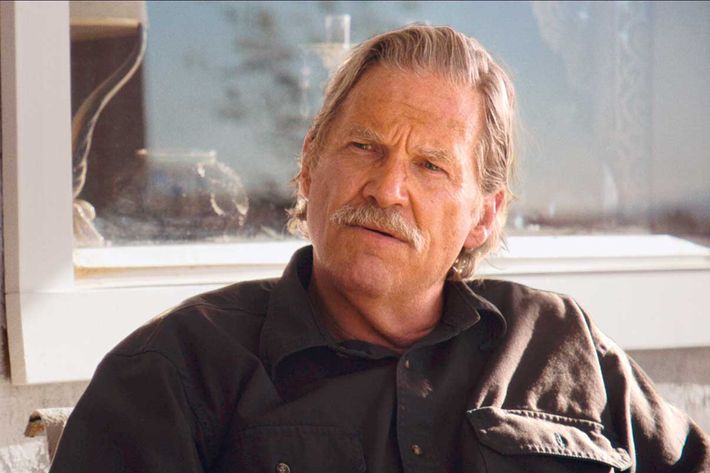

Jeff Bridges in Hell or High Water

The scene: Bridges plays Texas Ranger Marcus Hamilton, who’s been tracking a pair of brothers who’ve pulled off a series of audacious bank robberies. In this scene, he finally confronts his quarry, Toby Howard (Chris Pine).

Warning: Spoilers!

“You know, I have a lot of resistance to talking about this because it’s a bit like a magician giving away how he does a trick. I don’t want people thinking about my approach when they’re watching the movie, but I can say there was a lot to play in that scene. My character’s going through a bunch of different things. He’s having to deal with retirement. Then having had his friend and partner get killed by Toby’s brother. So there’s a lot of anger built up when he decides to go visit Toby. But he’s also got a lot of curiosity about what really happened and why Toby did it all.

When he gets there, he doesn’t want to blow his detective work by getting angry, and since they’ve both got guns, he doesn’t want to be killed himself and he doesn’t want to kill the guy. A lot of what you do in a scene like that, which has so much tension built into it, is just rest on the writing. There’s a lot of tension in it already. Thinking about it too much or trying to do too much can fuck up the whole thing. You just have to play the fucking scene, you know? Just be there as the character at that moment.

We were very fortunate to have a famous Texas Ranger, Joaquin Jackson, on set that day. I took a lot from him. When I sit down on a chair on the porch and take off my hat and hang it on my boot, that was something Joaquin did. His presence soaked into me. You think such a badass would be tough, but he had a real sweetness and gentlemanliness to him. You see that a bit when Toby’s family shows up in this scene and Marcus is so polite. That’s also when he says the line ‘The things you do for your kids, huh?,’ which is a key to the whole thing.

Chris and I rehearsed that scene a bunch. I like to rehearse in costume and get off the script as soon as I can so I can really get into the character. And David Mackenzie is the kind of director that doesn’t tell you too much, so you just kind of put all your ingredients in a stew and see how it comes out. This is kind of a funny thing, but you can figure it all out ahead of time, how you’re gonna do it, but once you’re there on set, you just let go and ask the spirit, the great entity, ‘Do with me what you want me to do.’ So in some takes of this scene it’d be, ‘Maybe put your weight on your other arm on the chair.’ Or ‘Notice the coldness of the beer in your hand.’ Just little things like that could get me further into Marcus at this moment in the movie.

One of the things that’s so intriguing about this scene is the ambiguity — about right and wrong and who is going to do what to who. There’s the line where Toby is telling Marcus, as he’s walking away from the porch, that they could talk sometime and he says, ‘Maybe I’ll give you some peace,’ and Marcus says, ‘Maybe I’ll give it to you.’ I do a little wave with my finger in the air there, and that’s also something I picked up from Joaquin. But this question at the end of the movie about giving each other peace — us human beings, we seek and long for peace, but we’re such a violent species. How do you reconcile that? You just stumble forward, looking for an answer.”

Michelle Williams in Manchester by the Sea

The scene: Williams plays the ex-wife of Lee (Casey Affleck), and in a wrenching confrontation, she tries to reach out to her damaged ex-husband, who won’t — or can’t — accept her olive branch.

“That scene felt sort of like an execution day: It was coming up and it was going to be shot and there was nothing you could do about it. We did happen to get a couple of pardons, because we were supposed to shoot that scene two, maybe three times before we actually shot it. A combination of production difficulties led to me showing up in Boston and being told, ‘We’re not going to do that today. You can go home.’ Each time, I would have a combination of deep release and, Well, what am I going to do with all of this? Because I’d been very carefully preparing myself emotionally and psychologically for a week leading up to it.

Finally the day came. It’s almost the last day of shooting — it literally could not have been pushed off anymore. You know those times in your life when you realize that this is the first time that you’re going to do something or the last time you’re going to do something, and everything around it becomes very vibrant? That’s what that whole day felt like. I remember getting dressed. I remember waiting in my honey wagon, which is a kind of jail cell that they hold you in on independent movies. I remember doing my makeup. I remember the songs that I was listening to. I remember the walk up to the steps. There’s a lot to get technically right, and there’s a lot to get emotionally right.

I think that both my character Randi and I imagined that scene a thousand times before it actually happened. It’s a very technical scene to learn because of the overlapping dialogue. One of [director and writer Kenneth Lonergan’s] many geniuses is that he writes in a way that seems like how people talk. And it has the feeling of being incredibly natural, but in fact everything is placed, and those overlaps are really crucial and they’re very hard to get if you can’t run the scene with somebody to learn the rhythm of it. But we didn’t rehearse it. I don’t think any of us wanted to. I would sort of say, ‘Hey, we should really run that scene, because, you know, it’s real complicated.’ But I think we had the same feelings the characters themselves would have had about that — we sort of want to do this, but most of me really doesn’t. It wasn’t something that [Casey] and I really worked on together at all. We worked on it separately and then we met in the ring.

Afterward, in a strange way, I felt relieved that it was over. And I knew that, inside of the scene itself, I felt a certain kind of flexibility that I hadn’t experienced before on film. So that was exciting. But I certainly didn’t leave the set thinking, I did a great job, and that’s going to be a great scene. When you do a play, you can tell when you’re winning or when you’re losing, when the audience is with you or not with you. But on a film set, you go home a little bit confused. Like, What was that? I hope it was okay. But I don’t know.”

Jovan Adepo in Fences

The scene: Adepo plays Cory, the son of former baseball player Troy (Denzel Washington, who also directed this film adaptation of the iconic August Wilson play). In this scene, long-simmering tensions between the two men boil over into a physical standoff.

“Denzel is definitely one of my heroes. In the first month we were working, I had a really hard time taking that element out of my work. Every time he would walk in, I would give myself five or ten minutes to be like, Oh my God, it’s Denzel. Then I’d have to suspend that. The big fight toward the end of the film was probably the most challenging to me for sure — the one that got physical. In terms of Denzel’s direction, it was a combination of things. Early on in the rehearsal process, Denzel would make reference to the fact that the scenes toward the end of the film have a lot of moving parts — but that the biggest thing to remember was this was the culmination of conflict between father and son. So during rehearsals, he’d emphasize the significance of space; when I say that, I mean the play in the theater versus on film. When you’re performing scenes of conflict onstage, you’re able to play toward the audience and kind of escape the conflict between you and your scene partner. Whereas in film, there is no place for you to go. It’s going to be constant eye contact. There are times where you might see me take a step toward him at a point of the argument. And then if he says something to me and I feel threatened, I might take a step back and he takes a step forward. It’s almost like a dance — like the choreography of a boxing match. We were able to do that because August Wilson’s words are already very poetic. You can almost snap your fingers to them. And that was something that we were very mindful of throughout the scene.

Denzel also had to keep reminding me to slow my speech down. When I get really excited — when Jovan gets really excited — I tend to speak fast. My brain is thinking too quickly. So he’d be like, ‘Slow down, slow down, slow down!’ The words that August Wilson was writing in the story are just as significant as the tone in which they’re spoken. So I think that’s why Denzel would remind me, ‘I know Cory is angry here, I know that you’re passionate and this is an important scene. But make sure you’re taking your time. And make sure you’re getting Cory’s point across, because if you are too caught up in the moment and you’re just blurting stuff, you can miss dramatic beats that are important to the scene. If you’re busy talking and running your mouth, you might skip right over it.’

Denzel wanted us to feel the tension between Troy and Cory. The standoff between them was inevitable: that point in every young boy’s life where he must become a man.”

Felicity Jones in A Monster Calls

The scene: Jones plays a single mother with both terminal cancer and a young son who’s struggling to comprehend it. In this scene, Jones’s character, Lizzie, must help her son face the truth, even as she realizes she must face it as well.

“The hardest scene was one toward the end of the film. My character has to really confront the fact that she’s going to die, and it’s been something she’s been avoiding. She doesn’t want to admit it. She’s trying to stay as strong as possible, and she doesn’t want her son to have to confront this. You know, their relationship’s very special. She’s a single parent. She had Conor when she was really young. So she’s pretty much been a teenager herself, she still has a rebellious spirit, a rebellious quality, and they’ve grown up much more as friends than with a strict parental dynamic between them.

So when the moment arrives, she finally has to trust everything that she’s given him and trust that he’s gonna be okay on his own. And it’s very hard for her to let go. On set, that was a very, very difficult scene. In some ways, it’s so much easier to play someone who’s fighting against something. But in this moment, the penny drops. She has to be very straightforward with her son, which is in some ways the most difficult thing to do.”

Jessica Chastain in Miss Sloane

The scene: Chastain plays cutthroat lobbyist Elizabeth Sloane, who’s trying to push through a gun-control bill. In this climactic scene, she’s hauled before a congressional committee to explain herself — and she gets to spring one final trap.

“It was after a very tough week. I think the week before we did this scene, we shot 24 pages, which I’ve never done on a movie before. We were shooting very quickly and trying to shoot a lot of pages, and I remember I said, ‘You guys, I feel like I’m going to have a breakdown.’ And I think this scene came after that.

And I have never been in a situation where I’ve had to prep so much. The terminology needs to be so specific and quick. That was something [director John Madden] kept talking about, about how rapid her pace needs to be. From the beginning of the movie, we’re always seeing Elizabeth on the go. She’s moving forward. If she were an animal, she’d be one that was in the water — she’s always pushing forward in this very fluid way, but very fast. Then in this scene, I remember John kept trying to slow me down. He said, ‘Just sit there.’ When we finished, he’s like, ‘Okay, I’m good,’ and I was like, ‘Uh, can I do it one more time, and can I do it really fast?’ And he let me do it, but he didn’t use that take. He was interested in her just really being present there, and I’m glad. You know, I saw the movie for the first time two days ago in its finished state, and I can really feel how she’s depleted at the end. I can see that, and I think he gave me really good direction for that scene.

Whenever I read any script with the intention of figuring out if it is something I’m going to be a part of, I try to feel the thoughts of the character. I don’t say the lines out loud, but emotionally I follow the story completely. I really put myself in the situation. I’m reading something to see if it’s a character I’m going to allow into my life — if I can understand them, even if they do bad things. If I can find some understanding with the person, even if they’re very different from me. To me, that will say, Okay, I can build on that, and yes, this is a part I can play. If I read something and I go, God, this person behaved so erratically, when there’s no justification even in writing why they’re doing this, then that’s not something I can play. I’m very detail-oriented and specific.

Also, on this movie I was always tired. I mean, I was up in Toronto, and I was by myself, and I didn’t have anyone staying with me. Usually I travel with my family so I never feel like a loner, but for Sloane I didn’t have that. And it wasn’t on purpose. I wasn’t trying to be, like, Method-y. It just happened that way, and I’m really grateful it happened that way. Because I’d finish a day of shooting, and then I’d have to go home, and I’d eat dinner, and then I’d start to memorize my five-page monologue for the next day or whatever I had, which, if you look at the script, you realize it’s a series of monologues just over and over again. And there was something so lonely and depressing about that, but they’re happy accidents. I just got to use that feeling while playing the character.”

Hugh Grant in Florence Foster Jenkins

The scene: In Stephen Frears’s comedy about a singer who can’t really sing (Meryl Streep), Hugh Grant is Jenkins’s boyfriend, St. Clair Bayfield. At the movie’s end, Grant has to convey his deep affection as Streep’s character nears death, and then come emotionally unglued.

“I was reading the script when I first got it and thinking, This is marvelous. I might be able to do this. And then I got to the part where Florence dies and the script says, ‘Bayfield sobs uncontrollably.’ I put a little question mark next to that. Sobbing uncontrollably is a tough thing; I’d never achieved it. After I signed on to the film, I had a year to dread failing to cry in front of Meryl Streep. Then, as chance would have it, the dying-and-crying scene was scheduled for the very last day of filming, so I also had to dread the crying scene throughout the entire shoot. Finally, on the day, I thought, I’m going to be exposed as a lightweight in front of Meryl Streep. So I sat in my little prefab dressing room and did what actors are supposed to do and went into all the saddest places of my life and put headphones on and listened to sad music, a group called the Military Wives Choir, and I’m thinking, I’m not sad enough. Then someone came and said it was time to go to set, and I sat down, and it’s my close-up, and I burst into hysterical tears. I mean, there were tears bursting out of my ears, snot pouring from my nose all over Meryl Streep’s hand. Afterward, I felt so smug — it was the happiest I’d ever felt on a film set, to think, I did it! I cried! Then, in the process of editing, Stephen Frears decided the scene was sadder without tears, because if an actor cries, the audience doesn’t. He was right, but I was devastated. So we reshot it with my just being sad, not crying — also not easy. Meryl was the one who said to me early in the shoot, scaring the living daylights out of me, that it’s the actor’s duty to be emotionally present in every scene: if it’s a sad scene, to be genuinely sad. There’s no one better at that than her, and to make the effort to match that was not something that came naturally. It’s a very American way of film acting, the belief that what the camera loves best is emotion. Meryl was always on about that, that people remember the emotions they’ve seen, not the lines. My acting has been more to do with light comedy, and there is really a technical side to that. There are rhythms and stresses that will make a line funny and rhythms and stresses that won’t. That’s not the case with scenes of heavier emotions. But, look, the Florence Foster Jenkins death scene is about love. Florence and Bayfield loved each other so much despite the odd shape their romance took. And so what got me sobbing was thinking about love. Because I do know love — and God, I sound like an absolute ass of an actor — but unconditional love, especially in the right state of fatigue or stress, can make you blubber. The secret is that I couldn’t have done that scene without having had my children. Particularly since I’ve gotten to middle age, love makes me cry. I’m touched by my love for my children and my children’s love for me. A terrible old softy I’ve become. And that’s what happened in this scene: It’s a death scene, but it’s actually not acted as a sad scene.”

*This article appears in the November 28, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.