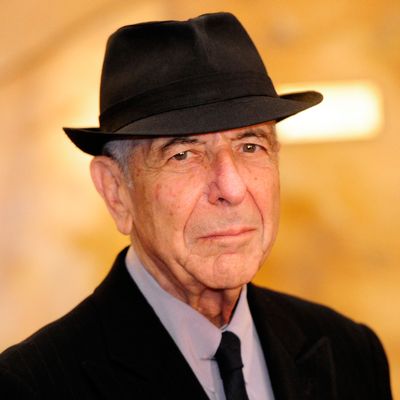

If you adored Leonard Cohen and you were honest, you could admit that you loved him because he was different — different from you, and different from the world at large. He wasn’t American, and his un-American nature was more than a mere matter of citizenship. Culturally and temperamentally, he lacked the insecurity that, more often than not for the worse, defines Americans and the world they have made. He was Canadian-born, but he wasn’t Canadian either. There was too much grandeur about him to place him anywhere provincial.

Perhaps the best way of phrasing it is to begin from his Jewish heritage and expand from there. Leonard Cohen was a diaspora unto himself, and distinctions between different sectors of the globe faded in the radiance of his character, or seemed to. He had been a writer long before he devoted himself to a career in music, and his best recordings tremble with the intensity of an authority that exceeds their melodies and rhythms. The character of most musicians is nothing more or less than the sum of their songs, but Cohen’s personality preceded his songs and stood independent of them. Music was a vessel temporarily containing his essence; it was not the essence itself. Cohen approached music as the Jewish people once approached reality. He was an experienced wanderer with a book — many books, really — to his name.

All the same, it’s clear that music was the field of culture best suited to expressing his spirit. His book and soul were full of chants and spells, not laws and doctrines. The legendary aspect of his poems and novels was housed more comfortably in music, with its boundless capacity for mythmaking. He was a substantial figure whose music had the power to give bodies to others, and not just bodies: They took on a flavor and a scent as well. Something in his voice ensures that Suzanne’s tea and oranges are more than thoughts or words. They have an origin and they are charged with redolence and an intention: that intention is loving. Like the gurus he consulted and the rabbis he descended from, Leonard Cohen cut a figure of embodied knowledge. Where others flickered, he shone; where others guessed, he knew, and knew precisely in the Biblical sense — carnally and eternally alike.

Sex and forever were the twin poles of the planet that his music called into being. They were united in a hidden core by cruelty, but this cruelty was free of all personal malice. His music was cruel as only time could be — in the eyes of God which see past time, lovers were always coming together, and always coming apart. This vision, which comes more naturally to women than to men, set Cohen apart from the cohort of iconic male singer-songwriters with which he was commonly grouped, and it endeared him to women and to women listeners in a way that Dylan or Paul Simon, more tightly bound to ego or transaction, never hoped to match. To love forever is a lie. Yet with a certain phrasing and from a certain angle it could, at the same time, be true, and Cohen had those words, and that angle. He offered the prospect of a life where love was mutually gratifying, as bracing as tea and as nourishing as oranges, and if life isn’t, and can’t be, sweet in such a way, it also can’t be lived without the illusion that it could be.

The reason Cohen is grouped with the people he’s grouped with is because they all emerged as popular artists in the same tumultuous ‘60s, and were eagerly listened to by the same mass audience: the (then) young, white, college-educated American class generally referred to as boomers. All differences in generation, tone, and integrity aside, Cohen’s Romantic music and message could nonetheless serve the same function of cultural and sexual emancipation that Dylan’s or Simon’s music did for this audience, and their gratitude to him was as limitless as it was sincere, and short-sighted. Cohen was of the Old World, and they were of the New; his sensibility was religious, and theirs was secular. The boomer revolution, inspired by television, necessarily contained within it elements of fraud, but Cohen, for all his looks, was fundamentally alien to television and its deceits. Born in the ‘30s, he belonged to the final generation for whom printed words took precedence over broadcast images, and he was taken up by the classier boomers as an emblem of the literacy and cultivation to which they gestured. He took being taken up as he customarily took everything: in stride. Love is hard to refuse, and when Cohen, late in life, was scammed out of millions by his accountant, that love restored him to financial, though not physical, health.

Leonard Cohen died on the eve on an election whose outcome spelled the end of everything he personally represented — love, faith, vision, serenity — as well as the end of a mode of white liberalism, born in the ‘60s, whose love, lacking conviction, was selfishly hoarded and selfishly spent; whose faith was mercenary and oblivious; whose vision never exceeded its adherents’ navels; whose idea of serenity was complacency caked with condescension. To paraphrase the Good Book, much will be forgiven Leonard Cohen, for he loved and knew much. But it’s hard to imagine that the generation that idolized him most will receive the same treatment.