In addition to being an annus horribilis for much of the country and planet, 2016 was unequivocally the worst mental-health year of my life. I won’t bore you with a play-by-play, but suffice it to say I was in a private hell stretching from early February to September, when I was prescribed a new medication. Throughout my life, I’ve lived with what I believe is a combination of bipolar II disorder and ADD (one can rarely be sure about such diagnoses), and for whatever reason, it decided that this spring and summer would be a good time to punch me in the brain with depression until I was dizzy and near-suicidal. Each night, in an effort to talk myself through the darkness, I’d scrawl out diary entries before retreating into sleep. If you were to read through them — which, please, don’t — you would see one phrase repeated almost daily, my singular mantra of flickering hope:

Endure, Master Wayne.

Those are words spoken by Alfred Pennyworth, as played by Michael Caine in 2008’s The Dark Knight. They come in a pivotal scene wherein he offers advice to his ward Bruce Wayne, the obsessive and perpetually miserable man behind Batman’s mask. It seems to Bruce that, due to seemingly impossible threats from the Joker, he has no choice but to give up. Knowing that feeling all too well, I’d whisper the phrase to myself during solitary moments, using Caine’s indelible Cockney drawl — en-JOO-ah, Mah-stah Way-een — like a prayer. In those instances, I was turning to the lessons of the Batman myth, simplistic though they may seem, to keep me on the right side of the binary between perseverance and self-harm. This was not a new strategy. For as long as I’ve consumed superhero fiction, Batman has been a sort of therapist for me.

It wasn’t until this year, however, that I became comfortable with that fact and realized why the character works so well as a coping mechanism. The trigger for my insight was the release of a comic book that, as this year closes, still echoes in my mind: Paul Dini and Eduardo Risso’s remarkable graphic memoir Dark Night: A True Batman Story, published in June by the DC Comics imprint Vertigo. Dini, the book’s author, was one of the lead writers on that beloved Batman chronicle of the early 1990s, TV’s Batman: The Animated Series. The show was my first exposure to the character, who stirred something primal in me, something I couldn’t put into words, and Dini’s episodes were among my favorites: “Heart of Ice,” “Joker’s Favor,” “Almost Got ‘Im” — they’re all canonical for geeks of my generation.

What we didn’t know was that Dini fell into an emotional nadir in the show’s early days. As we see in the memoir — passionately and often terrifyingly illustrated by Risso — Dini had struggled with emotional issues since he was a child, and they intensified in his early 30s. He was living alone and largely isolating himself from loved ones, preferring to lose himself in the childish delights of toys and home entertainment. We see him in Dark Night pursue deeply unhealthy romantic entanglements that never lead to real partnership. We watch as he uses the sharp wings of a freshly won Emmy to mutilate his naked torso after being rebuffed by a woman. Most crucially, we witness his wild downward spiral after a brutal mugging, the central incident of the book: Two young men in Los Angeles beat the shit out of him and he, after talking to some unsympathetic cops, just goes home instead of getting to a hospital.

“The pivotal moment in the story, the one when everything changed for me, is right after the attack,” Dini told me earlier this year. “I came home and slammed the door and I’m sitting there and there’s no one there to say, ‘Oh, my God.’ That’s when it really hit me, like, My life is empty.” Subsequently, he slipped into awful depression and alcoholic self-loathing. But what makes Dark Night curious and intriguing, and unexpectedly familiar to me, is how it reinforced that there’s a peculiar concept in the Batman legendarium, one that provides a helpful framework for understanding how to deal with ailments of the mind. It pertains to the book’s non-corporeal supporting cast: Batman and his rogues gallery, with whom Dini would routinely have conversations.

In the book, that process of communing with the Bat-world takes visible form: We see these interactions play out somewhat as they would in any other Batman comic, with the portly and unshaven Dini having chats alongside the characters he loves. “They become very real to me in a way that is hard to describe,” he explained when I spoke to him, clarifying that he doesn’t actually see the likenesses in front of him. “It’s like having a talk with yourself, and you want to put that into a character’s voice.”

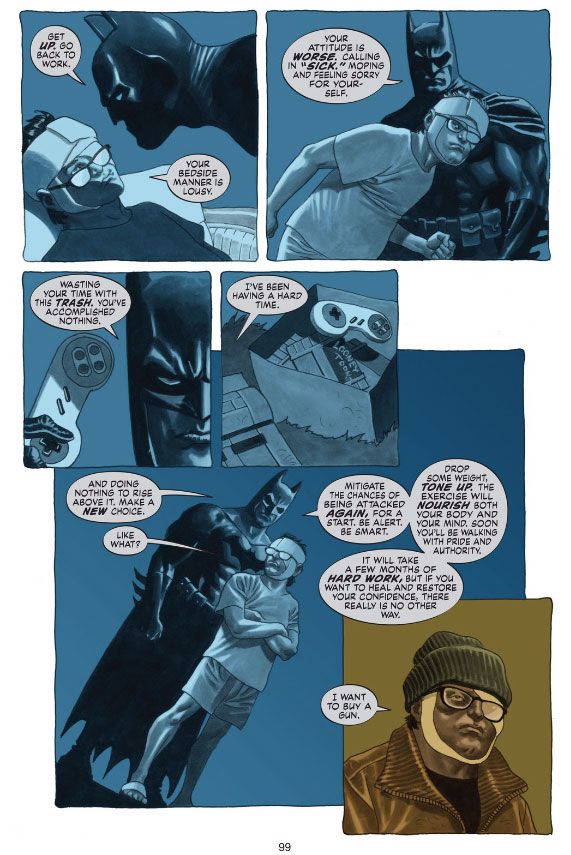

For example, at one point in the book a self-pitying Dini tells the Dark Knight, “I’ve been having a hard time.” “And doing nothing to rise above it,” Batman responds, looming a few feet taller than the bandaged protagonist. “It will take a few months of hard work, but if you want to heal and restore your confidence, there really is no other way.” Dini disregards this tough love at the time, and yet, by the end of the story, he learns that Batsy is the “voice that tells us when we get beaten down, we can accept being a victim or choose to be the hero of our own stories. And we make that choice by standing up.”

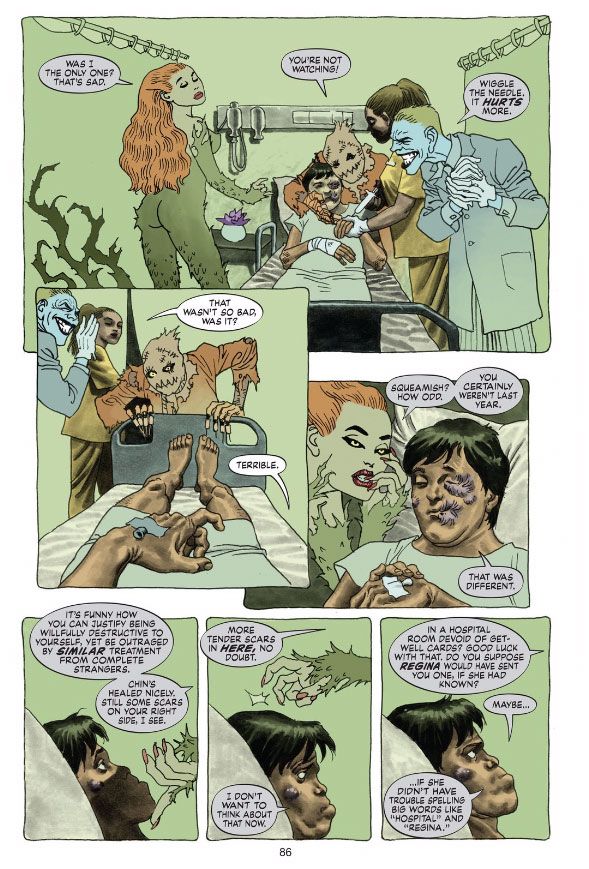

But it wasn’t Dini’s portrayal of Batman that moved me. It was his depiction of the bad guys. If Batman serves to offer tough-love advice for recovery, the bad guys are there to undermine those efforts with whispered notions of self-hatred that, though awful, are always more seductive when you’re in the hole. The Joker naturally advocates hedonism in the face of adversity. “Surrender to a wonderland of indulgences!” he cries while leaping around an underwear-clad Dini. “Nice big TV, stacks of movies, comics, and video games … all the toys you crave! And why not? You deserve them! Looky here! The phone numbers of every local restaurant that delivers!” The Scarecrow reminds Dini of his neurotic phobias. Poison Ivy tells him he’s shitty at romance. Mr. Freeze tells him to give up on human interaction. The Penguin urges him to drink. While Dini contemplates his pain, the Riddler riddles him this: “Who cares?”

Herein lies the unique conceptual framework that Batman tales offer. Bipolar II–induced depression is chronic. I’ve been ill for as long as I can remember, and probably always will be. I have plenty of good days, when life seems delicious and my tasks seem surmountable, but over and over again, I have the bad days, ones where the voices in my head — my own supervillains — tell me to give in to chaos. There’s the baddie who says I’m insignificant, the one who says I’m unable to love, the one who says I’m lazy, the one who says I’m defined by my failures, the one who says I’ll never be successful, and so on. They’re recurring characters. Sometimes, I’m fighting one; other times, a few of them team up. I push back as much as I can: I go to therapy, I meditate, I medicate. The antagonists go away for a while. But they never permanently disappear.

On a very literal level, Batman has been facing the same fight for the 77 years since his creation. His challenges, too, are chronic: He throws his enemies in Arkham, but they’re never there for long. Wins don’t last. There will always be new stories in which an individual force of evil or a team of villains will concoct a plan to take him down. Other superheroes have their own lineups of baddies, but Batman’s is easily the deepest bench, filled with vivid — and archetypal — characters who come back again and again. What made that scene with Alfred in Dark Knight so compelling was the manifest exhaustion of Bruce Wayne that any Batman reader or viewer always assumed: How can he possibly withstand the demoralizing truth of knowing all of his victories are provisional?

Well, he does it because he knows the world would be worse without him. If he were to give up, any agony he’d felt by having to fight would be dwarfed by the agony of all those who love and count on him after the villains win. That is, I realized, the essence of the Batman stories I think about when I’m depressed.

There’s Batman R.I.P., a story by writer Grant Morrison and penciler Tony Daniel in which our hero goes up against a coalition of villains who succeed in mentally destroying the Caped Crusader by ruining his life in an array of ways, but he gets the better of them with a fascinating tactic: We learn that he had prepared for this eventuality years ago by constructing a “backup personality” — a version of Batman that he could turn into if he was ever driven crazy, one that didn’t operate at full heroic capacity but was just strong and smart enough to take down his foes and allow him time to recover. Who among us with depression can’t relate to that notion of operating at diminished capacity long enough to get to the end of the current wave of awfulness?

Or there’s Batman: The Killing Joke, wherein Batsy refuses to let the Joker convince him that one mentally bad day can ruin a whole life. Or Batman/Planetary: Night on Earth, where he talks about the point of heroism being making sure people feel like they’re protected from those who would convince you the world is beyond repair. Or The Dark Knight Returns, where Batman talks about forcing the world to make sense when agents of chaos tempt you to do otherwise. Any fan who gravitates toward Batman stories in times of mental distress can name their own canon of tales where our hero’s resistance to the forces of darkness parallels their own — and what all those stories boil down to is that three-word Bat-catechism: Endure, Master Wayne.

When I write or say that phrase, I may be using the words of Alfred, but in directing them at myself, I’m imagining myself as a world-weary Batman. In those moments, it’s a reminder that if I give in to the voices, I run the risk of making a decision that would be devastating for those who love and count on me. Like Bruce in that scene, I need to remember that I’m capable of surviving, and that I can’t be deflated by the fact that my enemies will endure as well. Batman doesn’t stop, so we — the people like me and Dini, who rely on him, awkward though that might be to admit — don’t, either. 2016 has reinforced that there will always be new villains, arriving in a variety of forms both public and private, and at times it may seem like we can’t muster the strength necessary for battle. But we have this character to help us see the truth: that though the war against darkness never ends, it will always be worth it to get up, wipe the blood off our chins, put up our dukes, and fight on.