This week, IDW Publishing and DC Entertainment teamed up to put out a compilation of short comics entitled Love Is Love, a fundraising effort created in response to June’s mass shooting at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub. (All proceeds from its sale will go to survivors and the families of victims.) It’s comprised of a motley assemblage of pieces — some fictional, some autobiographical, some simply consisting of one image — about LGBTQ life and the struggle to find meaning in the wake of one of America’s worst hate crimes.

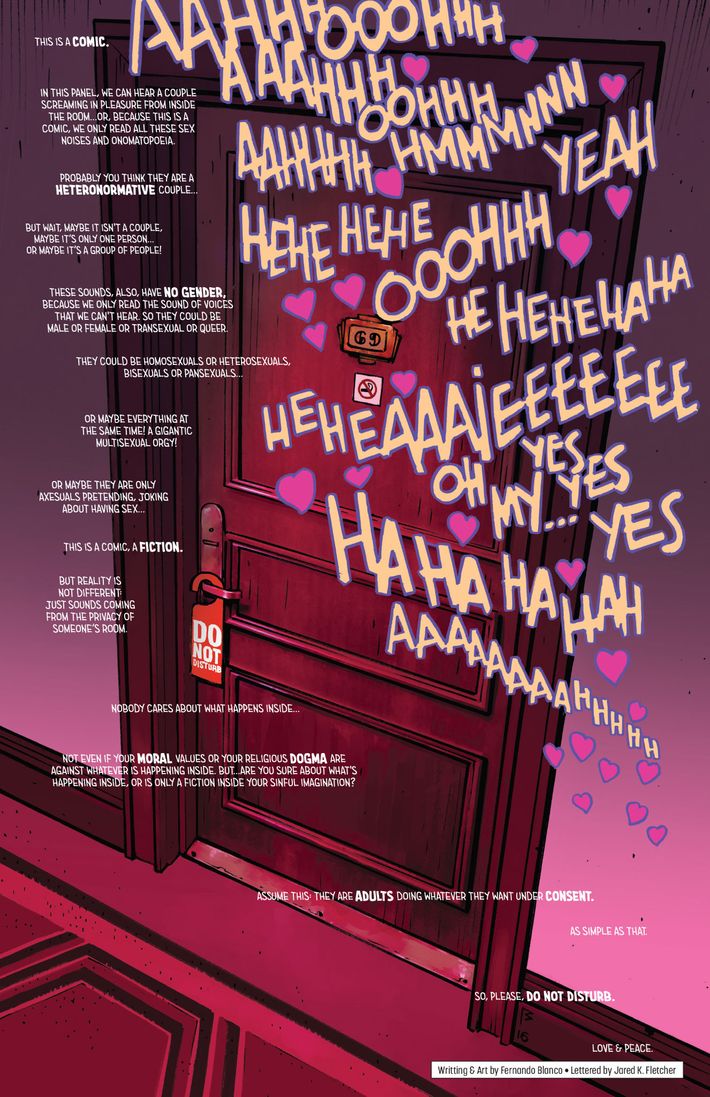

Looking through the book, I was particularly struck by page 70, which offers something unusual: a combo lesson about tolerance and formal composition. It’s written and drawn by Fernando Blanco, someone who isn’t a bold-faced name in the comics industry, but whose inventiveness here merits attention. There’s only one image: a door, seen from a slightly cockeyed angle at an elevated vantage point. It’s wooden and contains a no-smoking sign, as well as a do-not-disturb sign hanging from its handle, immediately conveying through visuals alone that we’re looking at the exterior of a hotel room (to be more specific, it’s room No. 69, which is nice). Another immediate message comes through the shading palette, which hops across the pink-to-violet range of the color wheel, thus subliminally forcing the us to think we’re going to talk about love or lust. But the representative images merely set the stage for the real action, which lies in the words.

The way text is used here is wonderfully unique. First, you have two completely different visual methods of conveying the alphabet, both crafted masterfully by letterer Jared K. Fletcher: On the page’s left side, the letters are linearly arranged and consistently sized; on the right, they shift in size and shape as they zig and zag across space. Those right-side words, mostly onomatopoeias, are interspersed with pink hearts — a kind of hieroglyphic representation of emotion within conventional text that comics incorporated decades before the advent of emoji. Without even thinking about it, a reader knows that they’re looking at a rational left-brain discussion and a visceral right-brain cri de coeur in the same visual plane.

What’s more, the discussion is about the cri de coeur. Blanco is teaching us about two things in just a handful of paragraphs: that we should be careful about the unconscious assumptions we make about “normal” modes of sexual affection, and that we should be just as cautious in the assumptions we make about any page of sequential art. “This is a comic,” the first line on the left declares right off the bat, ringing the school bell for our miniature master class.

“[B]ecause this is a comic, we only read all these sex noises and onomatopoeia,” we are told. Immediately, Blanco is identifying one of the magical aspects of comics, which is how they force the reader to fill in the blanks of representation. He’s making us realize that he’s already tricked us before we even started actively reading his argument — didn’t you already figure out that sex was happening behind that door, even though none of the right-side text says, “Oh, wow, this is great sex we’re having”? He then challenges us to ask about another assumption the reader was making before consciously thinking about it: “Probably you think they are a heteronormative couple,” Blanco says, just before he starts playing mind games.

Most of the ensuing text is about all the things that could be happening behind that door. “But wait, maybe it isn’t a couple. Maybe it’s only one person … or maybe it’s a group of people!” he says. It’s an exploration of the way we interact with text, but Blanco effortlessly blends it into a lesson on unconscious sexual politics. Just as we don’t know how many people are behind this wooden portal, we don’t know if they’re “male or female or transexual or queer,” nor do we know if they’re “homosexuals or heterosexuals, bisexuals or pansexuals,” “a gigantic multisexual orgy,” or — and this is the most fascinating proposal of all, about a sexual identity that gets far too little representation in fiction — “only asexuals pretending, joking about having sex.” Blanco and Fletcher have presented a thought experiment in superposition, wherein all sexualities and genders and groupings exist at the same time until we pick one.

Those paragraphs are, in their small way, stunning. With an economy and directness of words that the medium necessitates, Blanco stabs his way into our brains and makes us reassess everything about the page within the page itself. Magritte, that great inadvertent godfather of comics, would be proud. As if that weren’t enough, he goes on to remind us that, in a way, what we’re doing is insane, because “This is a comic, a fiction.” The door is just pencils and inks, and we don’t even have a visual representation of a room — just the idea and assumption of one. And just as it’s nuts to think we know what happens in an imaginary room, it’s a shame that we think we know what happens in any sexual situation that we haven’t directly experienced: “Are you sure about what’s happening inside, or is [it] only a fiction inside your sinful imagination?”

But rather than merely leave us dangling in our shame at the internalization of biased social norms, Blanco offers us a vision of how to move forward in our cognitive reasoning. “Assume this,” he says. “They are adults doing whatever they want under consent. As simple as that.” It is indeed simple, and yet, it’s something we have to actively teach ourselves to do. It’s appropriate that he lands on the social lesson, since that’s the primary goal of the entire book, but he’s also taught us something else: Always question your assumptions, about a comic panel or otherwise.