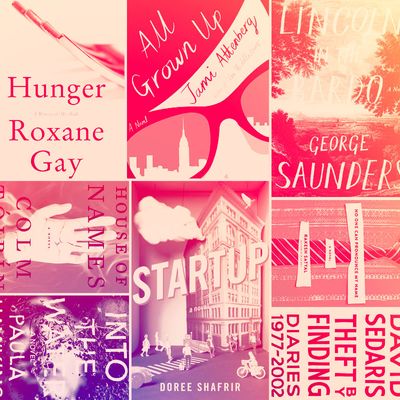

This week we’re looking to the year ahead by tracking down the most anticipated pieces of pop culture in 2017. Below, 25 books we can’t wait to get our hands on.

4 3 2 1, by Paul Auster (Henry Holt, January 31)

Compared to Auster at his most twistingly metafictional, his first novel in seven years is deceptively simple. Archibald Isaac Ferguson is born in 1947 (exactly a month after Auster), whereupon he splits into four different people with wildly divergent futures — though all court the same woman, and all are locked in the prison of one man’s DNA. —Boris Kachka

A Separation, by Katie Kitamura (Riverhead, February 7)

When her soon-to-be-ex-husband goes missing from a Greek island resort, his estranged wife must go search for him. What follows in Katie Kitamura’s third novel is more an existential mystery than an actual one, although the sheer deftness of her storytelling is nothing less than thrilling. —Maris Kreizman

The Age of Anger: A History of the Present, by Pankaj Mishra (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, February 7)

The Indian essayist’s ambitious world history of anti-progress backlash would have been almost as urgent if Hillary Clinton were president-elect, but the victory of an idiot demagogue surfing a wave of isolationist rage strengthens Mishra’s far-flung connections: ISIS and Brexit, Putin and Trump, and dozens of smaller shocks of self-destructive paranoia against a system that’s achieved so much, but never its promise of saving us from ourselves. —BK

Lincoln in the Bardo, by George Saunders (Random House, February 14)

The first novel by a master of short-story dystopias takes us not to some bizarre absurdist future, as in the linked stories of his Pastoralia, but to a quasi-Buddhist, tragicomic limbo in which souls are stranded and warped by their unfulfilled lives. Among those is the 10-year-old son of President Abraham Lincoln, who visits the boy’s entombed body during the bloodiest fighting of the Civil War. —BK

All Grown Up, by Jami Attenberg (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, March 7)

It’s 2017 and as a society we’re only just beginning to understand that not every love story needs to end with a wedding. Jami Attenberg’s latest novel is as funny, sexy, cynical, and yet hopeful as its heroine: a single woman approaching her 40th birthday whose journey will be relatable for anyone whose idea of happily ever after breaks the traditional mold. —MK

Ill Will, by Dan Chaon (Ballantine, March 7)

Dan Chaon was already a master of the short story well before he wrote his tense and delightfully twisted thriller, Await Your Reply. Ill Will finds Chaon back in thriller territory, with an even more propulsive narrative. It’s one of those books that looks big and heavy, but with pacing so tight it will likely only take a couple of days to read. —MK

Exit West, by Mohsin Hamid (Riverhead, March 7)

The author of The Reluctant Fundamentalist re-enters the global zeitgeist, using his own native Lahore, Pakistan, as the basis for an unnamed country whose descent into internecine violence sets off a couple’s refugee flight. The twist, which raises the stakes of an otherwise realistic story, is that the door to a safer country is a literal portal, a kind of wormhole into an uncertain future. —BK

The Idiot, by Elif Batuman (Penguin Press, March 14)

Intellectually rigorous yet always funny and inviting, Elif Batuman’s writing tends to hit home whether it’s in The New Yorker, n+1, or on Twitter. Her latest novel is set at Harvard in the mid-1990s but has the tenor of an old Russian epic, but one with abundant humor and a seemingly clueless freshman who has a lot to learn about the ways of the world. —MK

Sorry to Disrupt the Peace, by Patty Yumi Cottrell (McSweeney’s, March 14)

An unconventional detective story told from the point of view of one of the year’s most manically unreliable narrators, Patty Yumi Cottrell’s debut is an unnerving character study of a woman who lacks both common sense and self-awareness in equal measure. When she gets word that her adopted brother has killed himself, she returns to her less than idyllic childhood home to figure out why, and it’s hard not to root for her as she searches for clues and interviews witnesses, even if the investigation feels fruitless. —MK

Marlena, by Julie Buntin (Henry Holt and Co., April 4)

A novel that’s as invigorating and devastating as an intense teenage crush, Marlena is about the people we encounter in life — no matter how briefly — who leave a permanent mark. Julie Buntin’s stellar debut has the emotional sophistication of only the very best coming-of-age novels, so it’s no wonder it comes with a glowing blurb from Who Will Run the Frog Hospital author Lorrie Moore. —MK

Too Much and Not in the Mood, by Durga Chew-Bose (FSG Originals, April 11)

If you admire Maggie Nelson’s ability to combine the personal and the academic into a thrilling new art form, Durga Chew-Bose will be your next favorite writer. Her remarkable debut essay collection touches on art and literature and pop culture, but also feels intensely intimate, filled with stunning insights both large in scale, and small. —MK

Killers of the Flower Moon, by David Grann (Doubleday, April 18)

The true-crime genre takes a special touch to bring humanity to monstrous doings. The Last City of Z author and New Yorker staff writer David Grann has already written a thoroughly researched, spectacularly plotted narrative nonfiction tale that reads like a novel. So his latest effort, Killers of the Flower Moon, a book about a string of horrific murders of Osage Indians that took place in the 1920s, promises to follow in a masterfully similar vein. —MK

Startup, by Doree Shafrir (Little, Brown and Company, April 25)

BuzzFeed writer Doree Shafrir has covered culture incisively for a variety of internet media companies, so who better to write a biting satire of life in the New York City–based tech world? Part of the joy of reading Startup is deciphering which parts are based in fact and which are fiction, but even if you don’t care about guessing who’s who you’ll find the read a charming one. —MK

Borne: A Novel, by Jeff VanderMeer (MCD, April 25)

The author of the best-selling Southern Reach Trilogy returns to wow us with a sci-fi stand-alone: Borne takes place in a near-future dystopia where scavengers comb the streets of a seemingly abandoned city, where love and distrust and other things can grow and evolve at alarming rates. —MK

Into the Water, by Paula Hawkins (Riverhead, May 2)

Can Hawkins replicate the power — and success — of her breakthrough mystery, Girl on the Train? Many thousands will be eager to find out. As in her last novel, the big reveal will hinge on the ad hoc connections forged by tragedy, or in this case two tragedies: the discovery of the bodies of two different women, a teenager and a single mother, in the same river during the same summer. —BK

Priestdaddy, by Patricia Lockwood (Riverhead, May 2)

Twitter’s most famous poet (and one of our best IRL) finally puts to paper the story of what shaped “Rape Joke” and other memoiristic poems — a childhood as the daughter of a hippie Catholic priest. Setting this story in motion is a family crisis that leads Lockwood and her husband to move back in with Lockwood’s parents — older but no less eccentric — for eight revelatory months. —BK

And We’re Off, by Dana Schwartz (Razorbill, May 2)

A joyous contemporary YA novel by journalist and Guy in Your MFA Twitter mastermind Dana Schwartz, And We’re Off is a tale of travel, romance, and plenty of mother-daughter banter. That this will be the first book in a long line of delightful literature from wunderkind Schwartz seems inevitable and lovely. —MK

Woman No. 17, by Edan Lepucki (Hogarth, May 9)

The fearless author of best-selling dystopian novel California is back with a new must-read set in the same state, yet in a whole different world. Woman No. 17 is set in the lush Hollywood Hills (as so many great noir stories are), but at its center it does what Lepucki does best — explore the motivations and intricacies of complicated women. —MK

House of Names, by Colm Tóibín (Scribner, May 17)

Tóibín’s reputation for exquisite writing is long established, but it only went mainstream with the adaptation of Brooklyn, one of his finest historical novels. Anyone who read his novella The Testament of Mary knows he’s just as good at distant history as more familiar costume drama. This time his quarry is ancient myth, and the Greek theatrical cycle of death and vengeance that culminated in the crimes of Clytemnestra. —BK

We Are Never Meeting in Real Life, by Samantha Irby (Vintage, May 30)

Meaty (Curbside Splendor, 2015) author and Bitches Gotta Eat blogger Samantha Irby has been making her fans cry with laughter (and occasional sadness) for years. Now, FX is optioning her debut essay collection for a 30-minute sitcom, and her major publisher debut appears in May. Get ready for Samantha Irby to become a household name, and your life being better for it. —MK

Theft by Finding: Diaries (1977–2002), by David Sedaris (Little, Brown and Company, May 30)

The thrill of Sedaris’s nonfiction lies in the absurd details of his memories, burnished with enough polish and comic timing to wonder how true they are (after you’ve stopped laughing). Now we’ll finally have access to the raw material — fragments of the writer’s personal diaries that you might recognize from the banter in his prolific and hilarious live readings. —BK

Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body, by Roxane Gay (Harper, June 12)

The novelist and essayist on race, feminism, and Sweet Valley High is at her creative peak, a solid perch from which to contemplate her own life. Hunger focuses on her size — the way it shapes her world and the way the world has shaped her. Gay was open about her struggles to finish the book, leading to a year-long delay that only stoked her fans’ appetites and likely deepened the material, too. —BK

Blind Spot, by Teju Cole (Random House, June 27)

Cole’s Open City, a New York novel of walks and ideas, did to the classic flâneur narrative what Gay did for the essay — broadened the notion of what subjects and people count. His column “On Photography” in the Times magazine showcased his obsession with photography, and his second novel included a few of his own pictures. Pairing his own photos with impressionistic mega-captions, Blind Spot turns his photo obsession into a book-length photo essay. —BK

Sour Heart, by Jenny Zhang (Lenny, August 1)

The first book on the list from Lena Dunham and Jenni Konner’s Lenny imprint, Sour Heart is a story collection that delves into a world not captured in Dunahm’s TV series Girls — the immigrant experience of living in New York City. As Lenny’s first book author, Jenny Zhang is a coup — her wonderful essays and poetry have made her one of the most exciting young writers around even without the Lenny buzz. —MK

Sing, Unburied, Sing, by Jesmyn Ward (Scribner, September 5)

National Book Award–winning novelist Jesmyn Ward edited a beautiful essay collection about race in 2016 called The Fire This Time more than half a century after James Baldwin’s groundbreaking book, but it’s not until the latter half of 2017 that we get to read her next novel. Set once again in the rural South that she knows and conveys so intimately, Sing, Unburied, Sing promises to delight and astound. —MK