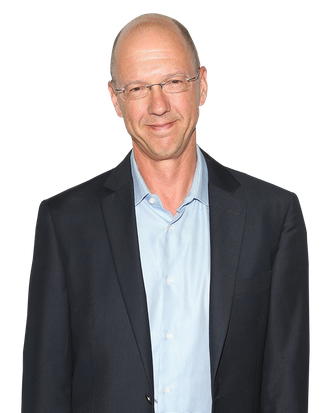

Since its January debut, Netflix’s One Day at a Time has generated critical acclaim as one of the rare TV remakes to match — and in some ways improve on — the promise of the original series. The fact that original producer Norman Lear was intimately involved in the process surely helped, as did the fact that the co-showrunners of the new version, Gloria Calderon Kellett and Mike Royce, both leaned heavily on their own personal life stories to imbue their creation with a sense of authenticity. One Day also succeeds by effortlessly bridging the TV generation gap: It’s an old-school sitcom that would feel very much at home on a broadcast network as well as a six-hour binge that isn’t at all out of place on a streaming service. To learn how it lives in both TV universes, Vulture rang up Royce — a former Everybody Loves Raymond executive producer — for an extended conversation about comedy in the digital era, the advantages of working outside of the broadcast ecosystem, and the surprising way in which Netflix executives acted just like their network peers when it came to a key decision.

You’re a veteran of the broadcast sitcom, as well as someone who’s worked in cable. Did you see a Netflix show as a chance to redefine the multi-camera comedy for the streaming era?

You know, the platform itself was attractive because of all the freedom it gives you, combined with the fact that Netflix is just less intrusive. As far as the format goes, it reminded a little bit of when Ray [Romano] and I were writing Men of a Certain Age. We didn’t stop to define it, you know, and say, “Well, this has gotta be a drama or this has gotta be a comedy or it has gotta be this or it’s gotta be that.” We just kind of felt our way. With this, obviously, it started as a multi-camera sitcom, in the Norman Lear tradition. So we didn’t reinvent anything — it’s just [Netflix] gave us the freedom to think about what the story required in this format.

How did being on Netflix change things?

I would say a couple of things. First of all, 13 episodes where you know they’re gonna air in order — because they’re not airing, they’re streaming — is a much easier thing to wrap your arms around. You know it’s not gonna be monkeyed with in terms of episode order. You’re just never going to get that on a broadcast network because of business reasons. You’re never going to get 13 episodes [airing] in a row. And if it’s a hit, you’re going to have 22, 24 — which is, you know, a great problem to have, but I can’t imagine serializing that many episodes, year after year. From a format standpoint, it’s more controllable.

Did having so much time to put the show together let you also play with how you wrote the first season?

We still broke the stories very old school. I think there’s a world in which you could rely on serialization taking over and substituting for good storytelling, you know? Where you’re just bleeding all the episodes into each other, and it allows you to never really resolve certain [plot] things. I think there’s a way in which it can be a crutch, and we wanted to make sure that if you just throw an episode up by itself, and not know anything about what happened before or after, that you’d still enjoy it.

How did the extra-long lead time help?

We got pretty ahead, but the second-to-last [episode] was really hard, where the husband comes back. That went through a lot of iterations, so we ended up breaking and re-breaking that one a lot of times. We had a target for the husband to return in a very surprising way around episode six or seven. And it was a perfect plan. Like, dramatically, we were going to get Penelope out of his orbit, basically get her on her way toward being her own single person and conquering certain single-mom obstacles. Then, we’d have him show up and suddenly it’s a “Just when you think I’m out, he pulls me back in” kind of a thing. The problem was, we realized he sucked all the oxygen out of her story. Suddenly, it was all about him. We had seven more episodes to go, and we didn’t want to make the show “will they or won’t they,” or whatever bullshit thing we would have had to do with him. We couldn’t think of a good way to get him in and out. So we realized it was better at the end.

It seems you could’ve made things even easier by writing all the episodes in advance, and then shooting them.

We could possibly do that next season, if we get that — which I hope we do. It’s more possible then than the first [season].

Why is that?

It’s a very odd and different work process than network TV. You don’t shoot the pilot, then have a bunch of months to rethink, maybe recast, blah blah blah. You shoot the “pilot” as basically episode one of a whole season. For a multi-cam, especially, that’s a really weird thing. We were in the room breaking stories for two months before we even shot the pilot. Rita Moreno was, of course, offered the part without auditioning. Not that we doubted her, but the first time we saw her read a line was at the table read for the first episode. By then, we’ve got nine or ten stories, and seven or eight scripts all dependent on certain things working. If for some reason we had blown a tire, in terms of cast or anything else, it would’ve really disrupted what we had planned. Casting is the most important thing anyway, but [with Netflix] you have this extra pressure of, “Oh my God, what if we screwed up somehow, and we have to rethink all these stories we already broke?”

You mentioned that Netflix executives didn’t micromanage you like a broadcast network might have. It sounds like that was the best feature of working in streaming.

It’s a sitcom that could be on a broadcast network, and in many ways the work process was very similar to what you do on a broadcast network. The difference — a big difference — was that, yes, the note-taking process was not egregiously heavy-handed. And all credit to Sony and Netflix for taking a light touch. So that [freed] up an enormous amount of time. We didn’t have to get bogged down in, “Oh my God, we’re turning this whole ship around for reasons that we don’t agree with.”

Let’s talk about the direction of the show. Pam Fryman (How I Met Your Mother) did the pilot and several other episodes. How did you work with her to blend the look of Norman Lear sitcom with a Netflix series?

It’s all coming from Norman. We wanted to use the tools of his era — or whatever you want to call it, the tools of his trade — to tell a good story. So long scenes, not exclusively, but as a stylistic thing. Close-ups, where possible, although in the HD era, close-ups are a different thing now. Sometimes it can get distracting to be that close on someone’s face the way Norman used to be in the ‘70s. He’d be, like, right in their face. [And] taking the time to let everything play out, to not have things cut off at the knees. The broadcast structure now almost demands that you cut away at the most interesting part. What’s the hook, you know? What’s going to bring people back from commercial? We didn’t have to do that. For example, when Rita gets up and says in Spanish, “You don’t raise your voice to your mother,” and they’re about to get in a fight about going to church, we don’t cut away, like, “Oh my God, what’s about to happen?!” and then come back. We play out the fight. We have these two amazing actresses slugging it out. That’s where Norman’s shows lived, and that’s where we wanted to be.

Another obvious [Lear technique] is to really go for the emotion. That’s the thing that we stress about the most: Did we earn this speech? Did we earn these tears? That’s pretty much where we start the storytelling. It’s almost always something emotional and dramatic that we’re trying to get to, and then the funny part always comes. To me, that’s the real art form that Norman perfected, mixing those two things. You have the treacle-cutter so you don’t get too full of yourselves, and at the same you can really get to a moment. There’s just something about the multi-cam when you get to that emotional moment — it’s a real person on stage, there’s people watching it, it’s very live. It’s very palpable and amazing. If you’re doing it right, you feel like you’re with the crowd that’s sitting in that audience. It’s very easy to not do right, and I’ve had plenty of opportunities to do that [laughs]. But boy, I just love it so much when you really get to something powerful that you’ve earned.

The first season really is like 13 one-act plays.

To me, a multi-cam sitcom is like a musical — it’s a style you have to buy into. Even the acting, it’s the hardest kind of acting. You can’t be naturalistic, you know? But you have to be somewhat naturalistic. You have to be a little bigger than life, but not in a cartoony way. It’s very easy to go way over the top, and it’s also very easy to try and do some movie acting, and that doesn’t work either. So you have to be this somehow relatable, believable person, who’s also bigger than life and has a personality that’s really attractive. You’re also talking in jokes. That’s not what a normal person does. It’s a style. It’s all execution. Everything is a tiny little sliver that can make it not good.

There’s no music between the scenes as a transition, which is a fundamental thing in most sitcoms. How did that happen?

When we were shooting it, we didn’t know which way it was going to fall. We hired a very good composer who composed some great music. He’s Cuban. We were intent on using it because, I mean, I’ve never done a show where I didn’t want to use music. We put it in a couple episodes, and it felt like it was making it feel sitcom-y. The music was fantastic, but it was just a stylistic thing. It was taking away. We just tried it a couple of times, did not love it, and when we took it away we were like, “That’s the show.”

Netflix obviously has no concerns about the use of profanity or nudity in its shows, even on sitcoms such as F Is for Family or The Ranch. Why’d you opt otherwise?

So that’s a funny story. In the first episode, there’s a line where [Justina Machado] says, “That’s some Jesus crap right there.” But in the [original] script, we wrote it as, “That’s some Jesus shit right there,” and then she turns and immediately apologizes. She turns and says to her son, “I’m sorry I swore,” and then she turns back to Lydia: “I’m sorry I said Jesus,” and she crosses herself. We’re not being edgy or anything like that; it’s a moment all parents have had. So to us it was very relatable. It fucking destroyed at the taping, of course, because they hear the word “shit” suddenly. Great, amazing moment. The crowd’s going crazy. Netflix is all for it. Everybody’s all for it.

But other than that, we didn’t have any plans to put swear words in. This character didn’t feel like she would be someone who swore in front of her kids, or did a lot of swearing in general. So it’s [a few months] later, and Netflix comes to us: “Can you do a clean version of that [Jesus line]?” I said yes, but was really against it, and so was Norman. Gloria was against it, but a little more willing to listen. So we shot it, where she says “Jesus crap,” and then, “I’m sorry I said Jesus so close to the word crap.” Still a good joke, but not nearly the moment that it was in terms of audience reaction. We thought, “We’re never going to use that.” More months go by, we’re editing the pilot. We keep “Jesus shit” in. And again, Netflix is like, “Can you please change that?”

Their reasoning was, it would be different if you had other episodes where there’s swear words. But it’s literally telling the audience something that we’re not going to end up doing; it’s just that one swear word. At first I was like, “No fucking way. That’s a great moment. I don’t want to lose it.” Norman was the same: “Don’t give in.” Gloria was much more reasonable, and saw the forest for the trees. It’s not worth having a moment that doesn’t represent the rest of the show in the pilot. It’s not worth having parents going, “Oh, well, I can’t watch this with my kids because this character is going to swear all the time.” So we sacrificed a great moment for the sake of giving a much better impression of what the series was. If we had gone down some road where this show that had a bunch of swearing in it, that’s different. But it just wasn’t that show. We want families to watch it.

Netflix hasn’t made anything official yet, but assuming a second season, would you want to do more than 13 episodes? And could you have more ready in 2017?

I would not argue with more. Whatever they want to throw at us is great. I think they’ve been pretty accommodating in terms of making the show creatively good. So I don’t think they would do something, even if they gave us more [episodes], that would diminish the quality by pumping out a whole bunch. But it is possible that there could be more episodes in 2017? I do not have any inside info. I think it’s possible, but that’s all I think.

We’re now in the age of President Donald Trump. How might that influence a possible second season?

From our perspective, we have to be relevant, but not necessarily topical. Our lead time for episodes is even longer than the networks. These are shows we shot starting in May. Imagine if we had written a show in May about Trump. You can’t be specifically topical because you don’t know what’s going to happen next. This is not an issue-of-the-week show. And not all of Norman’s shows were that. But this show does have characters who have issues that are important in America right now, issues that are relevant to their lives. And we want to explore those issues as they are relevant to the characters.

Do you think we’ll see the reality of Trump start showing up in a lot of TV shows, as it has already with Black-ish?

Without a doubt, people are talking about it. The world can’t stop talking about this. However you view it, positively or negatively, it’s the most incredible election results in a very long time. And the future is a fucking mystery. So I can’t imagine it’s not going to seep into people’s shows in one form or another. How that happens, I have no idea.

This interview has been edited and condensed.