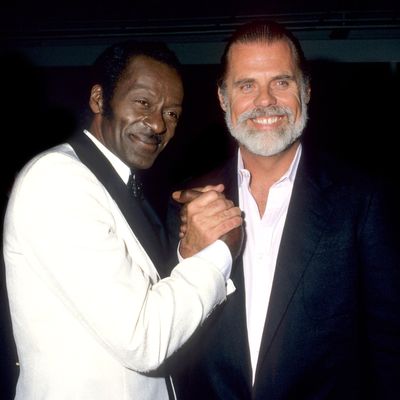

Director Taylor Hackford is a Hollywood fixture, having made his name with a string of first-rate entertainments — Officer and a Gentleman first among them — and then burnishing his reputation with Ray, the Ray Charles biopic, for which he got a Best Director Oscar nomination. Hackford has always been a music guy; one of his first films was The Idolmaker, an engrossing look at the teen-idol days of rock and roll, but most rock fans know him as the man behind Chuck Berry: Hail! Hail! Rock and Roll, a now-legendary documentary on the late pioneer.

As I detailed in my retrospective on Berry’s life, Hail! Hail! was intended to be the simple record of a celebratory 60th-birthday concert for Berry in his hometown of St. Louis. Keith Richards himself organized the event to acknowledge his debt to the guitarist, and Eric Clapton, Robert Cray and Etta James were on hand to help out. But Berry himself turned out to be peevish and cantankerous, and Hail! Hail! in the end became a puzzling portrait of a man with some issues. The film was a PR cataclysm of the first order. Amazingly, the story behind the film is even wilder. In the wake of Berry’s death, Hackford was kind enough to spend some time looking back on the experience. The following is a lightly edited version of our conversation.

Have you ever had a filmmaking experience like that?

No, nothing close. From a strategic point of view, if you’re making a documentary and it’s going to be a kind of celebratory thing where everyone’s saying nice things, that fine, but it’s not going to be very interesting. For me growing up in the ’50s, Chuck Berry scored my life. He was speaking right to American teenagers. He knew how to write songs for us. And so to me, it was an important film. But I also knew that he was going to be a very thorny character, and that makes for an interesting film. I said, chances are he’s not going to be able to hide who he really is, and the camera always finds that out. Little did I know that he was actually trying to recapture — or maybe he started to believe—his “bad boy of rock and roll” ethos. And he put us through it. He put us through it like crazy.

What was the first signal you had that things weren’t right?

It was gradual, because Chuck can be incredibly charming. He invited me to do the film, he was very solicitous and very nice, talked about movies I had made that he’d seen. But after he asked me to do the film, we met in Chicago, and Keith Richards came in — and so it was an opportunity for the musical director, Keith, and myself and Stephanie Bennett, the producer, to spend a little time and to plot out the film with Chuck.

Well, Chuck had this great big motor home, gigantic, and he talked about having driven up to Chicago [from St. Louis, where he’d gotten his start], and he knew Chicago because he recorded at Chess Records and so on. He was performing at the Chicago Blues Festival, and we went to the Blues Festival. Afterward, we’re driving with him in his motor home, and he turns on Michigan Avenue, which is like an eight-lane, one-way street. He’s going the wrong way! And we’re going, “Chuck, Chuck,” and he’s pulling up the street, and he hits his air horn. These cars are coming down the street at him and peeling off! He went for two blocks and then turned off. Now, I was thinking, was that on purpose? Did he make a mistake? He said, “It didn’t used to be one-way, it used to be two-way,” way back when he was there in Chicago.

When we were scouting the Cosmo Club in East St. Louis, he pulled the camper van in and backed up into a woman’s car, a woman from the neighborhood. We were inside, and this woman was sitting outside and going, “Chuck Berry, you come out here right now! You hurt my car!” And Chuck wouldn’t come out. He didn’t want to confront that woman in the street. The associate producer went out and made a deal for her, paid her $30 or something. I thought, well, that was an interesting one. Chuck, as bravura as he is, did not want to go out and confront this neighborhood woman from East St. Louis in the street about bumping into her car.

You actually were on a very tight time schedule making that movie. It has a very expansive feel — did you really make it in a week?

Well, my time in St. Louis was literally five days, that was my schedule. I was interested in going to the first prison that Chuck was in. [Berry spent three years in prison for what was basically armed carjacking.] He went from his 18th birthday to his 21st birthday in the Missouri State Penitentiary. Chuck had a relationship with them, and he would go up there and visit, and sometimes he would do concerts there. There was a kind of very nice, cordial relation between Chuck as an alumni of the prison. We pulled up to the gate, and had four women with us and about four or five guys in two different cars. Chuck was in his Cadillac and we were in a van behind him. He said, “It’s Chuck Berry,” and the guy says, “Hey Chuck,” and opens the gate. So we drive up, and we pull into this kind of field, this exercise yard in front of the prison. And a guard comes out, and she kind of seems confused, saying, “Did you have an appointment here?” He says, “No, I wanted to come up and show the people the thing.” All of a sudden, the bell rings and people are coming out on the yard. This guard is getting a little nervous.

I have Chuck’s video camera. He said, “Why don’t you shoot some stuff?” So I’m shooting as these guys pour onto the field. And his girlfriend and his daughter are wearing short skirts. The guys come out on the field and the guys say, “Hey Chuck, want to come back and see the cellblock?” He said, “Sure.” He leaves us. Now, we’re sitting there with this rather small security guard and a whole bunch of guys, maybe 300, that are now on the yard, and they’re seeing women — women in short skirts and high heels.

The women started getting very panicked, and the guard said, “Now, nobody show any panic, just start walking toward that building over there, the administration building.” And meanwhile I’m filming, and all these guys start surrounding the women. We get about a hundred feet from the thing, and the women go down — they fall down. I don’t know if they were tripped or whatever. And there’s probably about 300 hands that reach in, grabbing them, feeling them up. They were pretty shaken.

We got inside, and then the warden says, “What the hell are you doing here?” And Chuck says, “Well, I came by.” He said, “Well, you’re supposed to call and let me know this.” The place is getting pretty wild. The only way they’re going to get us out now is if Chuck gets with the prison band that he played with and do a concert. So he gets up onstage, and they’ve got all of us up on the stage behind him, and then they open the door, and we escaped.

In any event, Chuck asks for the tape back, I give him his camera, and I say, “God, this is great stuff. I want to use it in the film.” Meanwhile, the warden was pissed at him. He said, “If you ever come here again, you better let me know,” and then Chuck got angry at him. I’d gotten permission to shoot with my cameras, and they withdrew that. And I said, “Well, Chuck, give me the footage.” He said, “No.” I never got the tape back.

You’re captive of Chuck Berry in his world, and he could pull the plug at any moment. So the same thing with [my interview with Themetta, Berry’s wife]. He said, “That’s it. It’s over, shut it off.” You see that Chuck was controlling everything, and he’d only let a certain amount of things show. I wanted people to know that I was aware. I mean, the concert was an excuse — it was a wonderful excuse to be able to see the man, see him in his situation, see Berry Park, which was obviously a complete fiasco. In a way, it was like Citizen Kane living in Xanadu. One of my favorite shots of the film is the very end, where you see the guitar-shaped pool with stagnant water in it; and we walk around, and you find him alone in his old studio playing the steel guitar, right? It’s very much a statement about the man; he’s alone; he’s dark; he’s brooding, and at the same time brilliant.

Is it really true that on the first day of filming he just didn’t show up?

He was being paid $500,000 for his life and music rights. The first day of the shoot, I’m going over to East St. Louis to the Cosmo Club, and I say, “I want to start early, Chuck, because I’ve only got five days to shoot this, and I want to get everything.” He said, “Fine, fine.” I said, “Well, I’ll send a car for you,” and he said, “Nobody drives Chuck Berry but Chuck Berry. I’m driving myself.”

At seven o’clock, no Chuck Berry, 7:15, 7:30, and I’m getting worried. I call and talk to his assistant. She says, “Chuck left at 5:30.” And I’m thinking, maybe he got in an accident, maybe there’s a problem. Eight o’clock comes, 8:30 comes. Quarter of nine, a pay phone rings on the corner in East St. Louis, and let me tell you, East St. Louis was one of the tougher towns. They didn’t have a police force. The National Guard patrols the streets. It rings, and rings, and rings. Nobody answers it, because they thought it didn’t mean anything. Finally, somebody in the crew picks it up, turns to me and says, “It’s for you. It’s Chuck.” I said, “Chuck, where are you? Is everything okay? Where are you?” He said just these words: “Taylor, I just want you to know, everything’s cool between you and me.” And I go, “That’s fine, Chuck. What does that mean?” And then he says, “Let me talk to the producer.” Stephanie proceeds to have this huge fight with him on the phone. It’s a Saturday, the banks aren’t open, and he will not come to the set unless he has $2,500 in cash in a brown paper bag. And it took her until three. He didn’t show up until three. I started filming at three, after being there at 6 a.m. I don’t know whether he was playing with us, or whether he was genuinely neurotic about having the cash.

Did I read somewhere he tried to make the argument that he had agreed to appear only for 90 minutes of filming? And that you guys were saying, “No, it’s a 90-minute movie”?

Yes. He did everything possible to extort. It was probably the greatest nightmare of any filmmaking experience I’ve ever had. I look back on it and I’m laughing, but you have to understand, we were being sabotaged at every step. And every day, you didn’t know whether you were going to shoot the next day. The first concert [at the St. Louis Fox] was supposed to start at 8:30, and the second concert was going to start at 11:00. The first concert started at 11:30, and the second concert started after 2 a.m. Didn’t finish till 4:30 a.m.

He’s such an enigma. You’d think that someone as canny and money-conscious as him would say, “I got Eric Clapton here, I got Keith Richards, let’s make me look as good as possible,” but it seemed like he sabotaged himself.

He was trying every step of the way. I had five days. Then he says to me, “On Wednesday, I can’t shoot.” I said, “What? I only have five days.” He said, “I got a gig at the Ohio State Fair.” I said, “You got a gig? How could you have a gig? You’re the executive producer of this whole film. You knew we were going to be here.” He said, “I’m getting paid 25 Gs, that’s the way it is.” I said, “You’re getting paid $500,000 for this movie!” The rug is getting pulled out from under me, right before the film starts. I said, “Fuck it, I’m going.” So I go back to say to him — I say, “Chuck, I’m going to go. If you’re going to the Ohio State Fair, I’m going.” He says, “That’s fine with me, but I ain’t paying.” Classic Chuck Berry.

But you know what? That sequence turned out to be one of the more interesting sequences in the film. It defines what Chuck Berry did for 35 years. He went out every weekend; he played a gig; he didn’t take a band. He got a pickup band. Every rock-and-roll band should know Chuck Berry songs. He collected his money in cash. He flew in; he did his concert; people went nuts. He got back in his rental car, went back to the plane, and flew back. I had him getting into his car in the short-term car park at 12:30 at night. And he made 25 grand.

Unbelievable.

So I shoot that sequence because I just was not about to get blanked. I needed to shoot something that day. It turns out later, when I talk to Bruce Springsteen about being in the film, Springsteen says, “I’ll do it if I can talk about when I and the E Street Band were nobody, and we backed up Chuck Berry.” So Springsteen, giggling the whole time, tells this story about Chuck Berry. And I use his story to narrate that sequence, because nothing had changed in 15 years since Springsteen had done this.

Keith and I realized we had to wing it. We realized that all the planning, everything that you might do, was going to go right out the window, and that it was like riding a Brahma bull. He was going to buck you off sooner or later, but you had to try.

Dick Allen, his booking agent for 40 years, told me the story about the French May Day concert in Paris. He and Jerry Lee Lewis were on the bill. It was the socialist government, that’s their biggest holiday of the year, and they had this huge thing outside of Paris. So Chuck got his normal $75,000 fee, and Jerry Lee did, too. Then they were deciding who was going to go on first. And Chuck never in his entire career cared about going on last. When he was first touring, he liked to go on first — even though he had the most hits — because he could go on, get off, and then kind of scour the crowd for a young piece of jailbait that he could screw before they had to get on the road again. But when Chuck realized there was money involved, he and Jerry Lee had a big fight about who was going to go on last. And Chuck said, “You know, you pay me a little bit more money, and you can let Jerry Lee go on last.” They drive out to this fairground where this is happening; and as they’re driving out, they just see thousands of cars. And they get there, and Chuck realizes that there are 300,000 people there for this May Day thing. He goes, “No fucking way that I’m going onstage unless they pay me triple or quadruple what they said they’d pay me.” And Dick Allen described the French going, “No, Mr. Berry, you do not understand. We are socialists.” And Chuck Berry’s going back, “Fuck socialism, I want my money.”

He wouldn’t go on. Meanwhile, the French fans are getting drunk. It’s in the afternoon; it’s hot; they’re getting drunk; they’re starting to get unruly. They said, “There are no banks open.” Chuck says, “You see all those people out there selling wine and selling food? They got money, they got the cash. You get it from them.” And they went out and they collected, I think, an extra $100,000 for him, and then he finally went on. And, of course, because he had agreed to go on first, Jerry Lee couldn’t go on. He held up the entire French socialist movement. That’s Chuck, he didn’t care.

When did the incident happen where he brought McDonald’s into the fancy restaurant? Was he being kind of punk rock about it, or was he insecure, or was he clueless?

I think he was being punk rock about it. We went to a nice restaurant, and Chuck brought some McDonald’s in and opened it up, and was eating it right there. Chuck loved food. He took me to some great barbecue joints in St. Louis. I think he really did like to eat like a working-class person. I’m not answering your question, because I don’t really know. I don’t know whether that was a kind of statement — “You people are fancy, and I’m going to show you what I eat” — or he genuinely didn’t want to eat fancy food, and felt more comfortable eating McDonald’s.

Did you get any indication of his sexual issues while you were there?

Well, I mean, he came on to every woman on the film, completely. I mean, he would try. There wasn’t anything horrendous, but he did try to bed every woman that was there, including Stephanie Bennett, the producer. But again, was that a surprise? I don’t think that was a surprise. Everybody knew that Chuck Berry had a real sexual jones. But once they turned him down, then he didn’t push it. But he certainly tried.

Was there a moment when things started to go south between him and the other musicians?

Everybody was thrilled to be there. It never went south with Eric [Clapton]. I mean, he admired Eric. It’s just that with Keith, he had made up his mind that he was going to give Chuck Berry a great band. Keith wanted to rehearse. I don’t think Chuck was prepared. He’d invited us there, but I don’t think he was prepared for the intrusion on his life.

One other thing that I loved that I think is revealing. We were shooting at the concert at the Fox Theater, which is this huge movie palace in St. Louis. Chuck told the story about when he was a little boy: he goes up to the box office; he puts his money up there, and the woman says, “No, take your money, get out of here. Your kind can’t come in here.” Within his lifetime the Fox Theater was segregated, and now he is headlining it, which is a great kind of statement.

But what was most important to me about that whole moment was when I asked him, “What was the movie you wanted to see?” and he said, “A Tale of Two Cities. Charles Dickens and A Tale of Two Cities starring Ronald Colman.” I can’t fucking believe it. Here’s this little kid who doesn’t want to see a gangster movie, or a cowboy movie, or whatever was big in his time; he wants to see a classic literary piece, A Tale of Two Cities. That tells you so much about who Chuck Berry was. Yes, he was an outlaw; yes, he went to jail; yes, he was all those things, but words were important to him, and he was a first-rate rock-and-roll lyricist.

I think people don’t see how different the ’50s were. Think of some God-fearing, nice American man seeing his daughter going to a Bo Diddley show. I can’t imagine what people thought.

In the film, Little Richard is so hilarious. He said, “You imagine, there’s rock and roll, and they got this big, black, greasy guy with all these white girls.” And they said, “No, no, no!” And Chuck and Bo are laughing. It’s the truth. In the ’50s, pop music was Perry Como and Patti Page. And this music came out of nowhere. And the difference was, black people listened to the blues, and they sold blues records, that was it. It was anything but mainstream. Elvis got rock and roll in white teenagers’ bedrooms. But then with Chuck, and Richard, and Bo, teenagers started listening to all this music, and then they wanted to see them live. And then, of course, parents started to say, “Wait a minute, I’m not dropping my daughter off and my son off at places like this!”

Do you have any sense of what the root was of these insecurities, and the peculiar waspishness, and the irregularities? Did you get any sense of where any of that came from?

There was a huge amount of resentment that Chuck felt, as an originator. It’s a normal situation where somebody comes up with the first evocation of an art form, and they’ve done it, and they’re brilliant at it, and then everybody comes on afterward and refines it. The Rolling Stones adapted Chuck Berry, the Beatles adapted Chuck Berry. The Beach Boys copied Chuck Berry. Prince told me that without Chuck Berry, he wouldn’t have been there. I think Chuck understood that. Right in front of his eyes, he had Keith Richards, and everybody was like falling all over themselves — “Oh my God, we’ve got the Rolling Stones here. It’s Keith. Oh, Keith.” Keith was there to celebrate Chuck, but people were screaming for Keith.

He did profit from the British Invasion, but he was also looking at the fact that they had hundreds of millions of dollars, and he just had a few million — and he had created it all. Chuck could play; he could sing; he could do the duck walk. The brilliance dripped off him. He was a star. But he was a black man. Maybe it was having that talent and realizing that if he’d been born white, he could have been one of the biggest, most successful, and richest performers ever.