It’s hard to pick which scene in “Old Man Logan” is the wildest. The epic tale was first published by Marvel Comics in the pages of X-Men spinoff series Wolverine at the turn of this decade and is a huge influence on this weekend’s superhero tentpole picture Logan. It remains as shocking today as it was when it came out, a decade ago. The story is built on the premise that the venerable Marvel universe has gone all dystopian and cockeyed, which leads familiar archetypes to be warped to the very edge of recognition. In choosing the most insane moment, you might select the part where the Hulk eats Wolverine, only for the latter to burst out of the former’s stomach. Or the scene where a T. rex possessed by an extraterrestrial symbiote runs after the heroes. Or the incident that powers the whole narrative, in which a hypnotized Wolvie bloodily murders all of his X-Men pals and leaves their stunned corpses in a gruesome pile at the Xavier School for Gifted Youngsters.

In other words, “Old Man Logan” is something of a turducken of terror for the Marvel mythos. At the same time, the story arc — written by Scottish provocateur Mark Millar and penciled by action-scene master Steve McNiven — filled with a remarkable degree of passion and reverence for the company’s eight-decade-old legendarium, providing a vision of Wolverine built on the creators’ admiration for one of their employer’s greatest characters. Thanks to frustrating copyright disputes and the wishes of Logan auteur James Mangold, the filmic offspring of “Old Man Logan” isn’t quite as nutso as the source material, but its influence is raw and apparent to anyone who’s read the story. Without it, Hugh Jackman’s swan song would be very different.

In fact, the Marvel brand, as a whole, would be different without the story. With Logan on the way, it’s time to acknowledge “Old Man Logan” for what it is: the most influential single X-Men story in a generation. There have been other X-tales in that stretch that have introduced famous characters or ideas, but only “Old Man Logan” has given birth to two subsequent comic-book spinoffs, an ongoing reinvention of the character, and its own movie. In a world where the American superhero comic has become one of the most lucrative items in global entertainment, it’s worth picking apart how and why “Old Man Logan” became such a key part in the evil-fighter industry.

Spoilers for “Old Man Logan” — but not Logan — below.

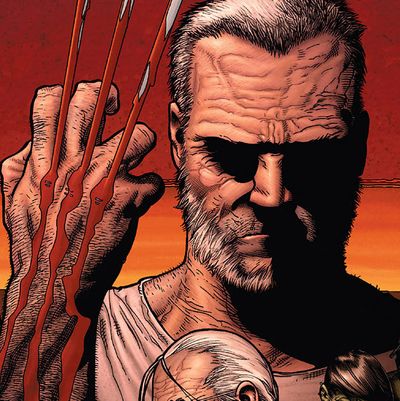

It began as a doodle. As the aughts drew to a close, Millar had become one of Marvel’s golden boys, a go-to writer whom you could count on for comics that, while inconsistent in quality, were always memorable for their big ideas and oft-horrifying violence. Despite his reputation for boundary-pushing, he also obviously loved past classics in both comics and film, including Westerns. “‘Old Man Logan’ came from drawing a picture of Wolverine where his hair was cropped and gray like Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven,” Millar told me in a 2013 interview for a New Republic profile. “And I thought, Well, that’s quite interesting. An old Logan” — Logan being Wolverine’s traditional civilian name. “Maybe he hasn’t popped his claws and he hasn’t picked up a gun in 30 years.”

Millar’s mind wandered and percolated. “I thought, Well, that’s interesting. Why hasn’t he popped his claws? Then I thought, What’s the one thing that would make Logan not pop his claws? And it would be hurting the people he loves. So then I had to think of a scene where he hurt the people he loves, and how to make that happen.” And boy, does Logan hurt the people he loves. Though the reader doesn’t find out exactly what happened until midway through the epic, it’s made clear throughout most of the narrative that the X-Men went the way of the dodo during the central incident of the world of “Old Man Logan”: a day when the superheroes fell. Decades prior to the story’s main action, all the various baddies of the Marvel Universe finally got their act together and joined up to take on the good guys on one fateful night. Evil won, nearly all of the heroes were killed, and the capos of the bad-guy uprising divided America up among themselves.

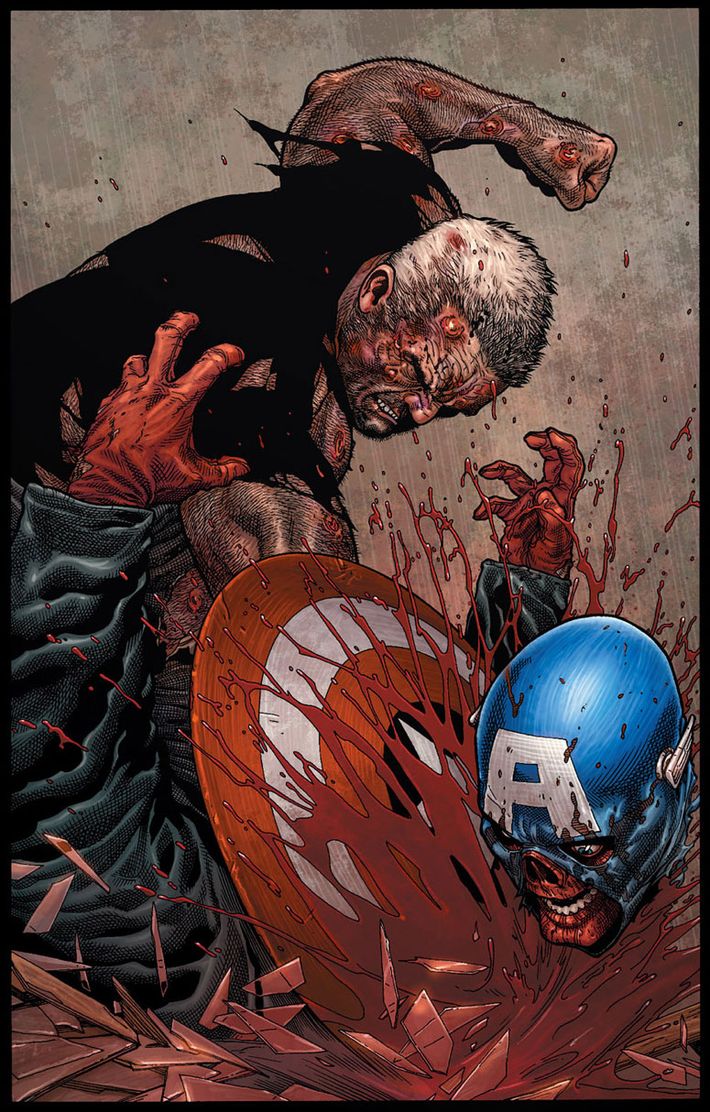

What we eventually learn is that Logan got the rawest deal of all. When a squadron of nemeses came to the X-Men’s headquarters, Wolvie rushed to lethally take them all down in a horrific, decapitation-filled fight that stretched on and on until it seemed he had finally won. Only then was it revealed to him that Spider-Man foe and master of illusions Mysterio had made Logan think he was killing villains, when really, all the villains he saw were X-Men and their child wards. He had carried out a wholesale X-massacre.

Traumatized beyond belief, Logan wandered to nearby rail tracks and tried to kill himself by letting a train run over his neck. His healing factor and adamantium skeleton kept him from losing his skull, but it gave him the masochistic pain he desired, and afterward, he vowed to become a nonviolent pacifist. In Millar’s rendering, Wolverine then moved out to California and set up a quiet homestead, Unforgiven-style. He resolutely avoided conflict and suffered the abuse of a local mafia run by the Hulk, who went turncoat years before. Of course, retirement never lasts in comic books, and one day Hawkeye — now functionally blind — comes to Logan and asks him to act as a driver on a road trip to the East Coast to help out some rebels there. Needing cash, Wolvie says yes. Insanity ensues.

Millar brought the pitch to editor Axel Alonso — no stranger to gruesomeness, having edited at DC Comics’ outré Vertigo imprint — and Alonso was overjoyed. “A Spaghetti Western set in a brutal, dystopian-future Marvel Universe? What’s not to like?” he remembers thinking. “The high concept provided Mark maximum flexibility to go big and gory and deconstruct the entire Marvel Universe.” He gave the Scotsman a green light to go nuts. Millar went to penciler Steve McNiven, with whom he’d collaborated on 2006’s Civil War mini-series, and brought an already finished script. “It read like a fever dream,” McNiven recalls.

The resulting story, published in 2008 and 2009, works largely for three reasons. The most immediately noticeable one is the artwork of McNiven, inker Dexter Vines, and color artist Morry Hollowell, which is as photorealistically dynamic as it is astoundingly gory. The not-so-hidden secret about Alonso is that he loves extreme and provocative storytelling, even at the expense of good taste, so the artists had a remarkably long leash. Thus, we get spectacles like Wolverine decapitating the Red Skull with long-dead Captain America’s shield; flashback-Wolverine stabbing what he thinks is villain Bullseye, causing a gush of what looks like gallons of blood; and perhaps the most famous shot, the aforementioned emergence of Logan from the Hulk’s gut (Alonso’s favorite scene). Some may see the violence as excessive and cynically titillating, but one can’t deny that it was uniquely visionary — to paraphrase Wolverine’s old motto, McNiven’s the best there is at what he does, and what he does isn’t very pretty.

The second thing that makes “Old Man Logan” shine is its combination of inventiveness and reverence. Millar is, to put it mildly, an inconsistent scribe, and though some of his work is as good as comics have gotten in the past 20 years (The Authority, Ultimates), some of it is brackish (Jupiter’s Legacy, Nemesis, Superior), and a lot of it is abhorrent (Kick-Ass 2, Wanted, The Secret Service, Super Crooks). But what never changes is the ambition of Millar’s elevator pitches, whether brilliant or ill-conceived. He’ll take a familiar concept or character and ask, What if it were tweaked just enough to make it radically fresh?

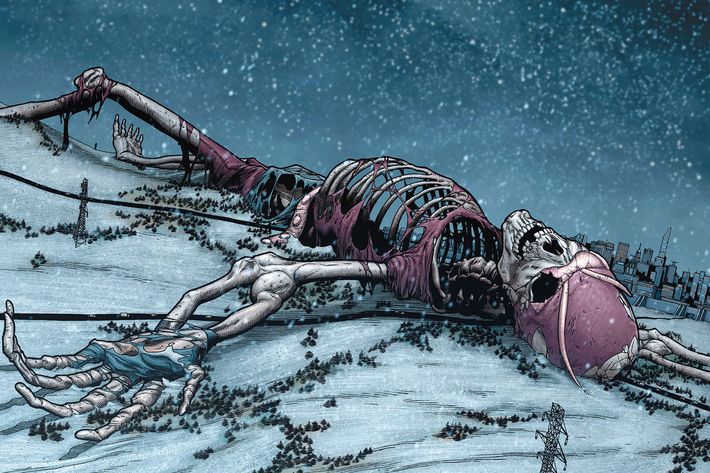

“Old Man Logan” is filled with such notions, all built on Millar’s extensive knowledge and love of Marvel mythology. What if Giant-Man died while at maximum size? You’d get a terrifying costumed skeleton the size of a small town. What if the Hulk’s gamma radiation started to grant superhuman strength to his Bruce Banner form? He’d be able to punch people across a city block while looking like an eerily scrawny old man. What if Thor perished in battle and there were no people honorable enough to overcome his hammer’s Excalibur-like resistance to the hands of the unworthy? It would be stuck in the ground permanently and become an immovable tourist attraction. We get appearances from great superhero ephemera like Spider-Man’s Spider-Buggy and the dinosaurs of the Savage Land, and we get the truly rad sight of Wolverine flying in the late Iron Man’s armor. It’s all done with the giddy delight of a kid playing with action figures, in configurations only limited by imagination.

“Old Man Logan” is a story about the Marvel Universe that could really only work with Wolverine. “Like Batman in The Dark Knight Returns, it’s not hard to imagine that he will survive whatever apocalyptic nightmare befalls the Marvel universe,” says fellow Marvel star writer Brian Michael Bendis. “It’s not hard to imagine him like Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven: the last cowboy left alone with his memories and sins.” Millar gets the character on a level that’s uncommonly deep.

That leads us to what is perhaps the most important factor: the big heart of “Old Man Logan.” Much of Millar’s work is infamously cynical, relying on shock value and little more. Not so here. True, Wolverine brutally murders the evil Hulk, but then decides it’s his responsibility to take care of the Green One’s infant son. Hawkeye has secrets and contours that show a reverence for the way the character was portrayed before his big-screen reinvention (and before Millar, himself, inspired that reinvention in Ultimates); Doctor Doom’s wordless cameo is granted an awesome nobility by McNiven’s illustration of his eyes and posture; and above all, Millar’s writing shows a sincere love for Wolverine in a way that’s rare in comics. One moment stands out. Throughout the story, Hawkeye keeps getting irritated with Logan for not popping his claws, prompting the weeping hero to recount his tragic tale over a campfire. “Now you just try tellin’ me Wolverine didn’t deserve to die,” he says after it’s done. Hawkeye furrows his brow and says simply, “I wouldn’t dare.” Nor would we.

And nor would comics creators and filmmakers who have read the comics story and been inspired by it. The notion of an aged Logan whose familiar self mostly died long ago and who is reluctantly coming out of retirement has become a core part of the Marvel brand. First came a 2015 mini-series titled Old Man Logan, which returned to the dystopian world of the original story. Millar left mainstream superhero comics not long after the original “Old Man Logan” hit stands, so Bendis took over and layout genius Andrea Sorrentino replaced McNiven. After that, the older Logan was shunted back in time and has lived in the contemporary Marvel universe ever since, gaining an ongoing series, also titled Old Man Logan, written by the fascinating Jeff Lemire and still drawn by Sorrentino. In fact, the usual version of Wolverine was killed off in 2014, so Old Man Logan is now the only version of Logan available in comics.

As if that level of legacy wasn’t enough, the story is also the biggest single comics influence on the Logan film. Mangold found “Old Man Logan” fascinating, and says he based much of the movie’s aesthetic on it. The story is wildly different, in no small part because Fox owns the rights to X-Men but not to the rest of the Marvel Universe, meaning you could never get the parts about Hawkeye, Red Skull, Thor, and the rest onscreen. Nevertheless, the unprecedented violence, the retirement out West, and the central notion of a road trip all very much make their way into the film. Even the title is a very obvious homage. In short, “Old Man Logan” has lived on in a way that rivals all the great X-Men stories of the past. Film adaptations are the most obvious measure of impact, and all the other big X-movies (with the exception of Deadpool, which is only barely tied to the X-Men film universe) are based on stories published between 1963 and the mid-1980s. Not so here.

The last revolutionary development in X-Men comics history was probably the visual redesign and cartoon-friendly tonal shift of the 1991 franchise retooling, which is now in the distant past. Since then, even the best X-Men stories have either been derivative of past classics or subsequently ignored by filmmakers and comics writers. (Grant Morrison’s fantastic run on New X-Men in the early aughts being the best example of the latter.) But “Old Man Logan” lives on, a boldly refreshing vision that’s unlike anything published before it. It was the first new story to alter the course of this venerable franchise’s development in a very long time, no small achievement in a genre as creatively conservative as superhero fiction. It’s a good thing for Fox, Marvel, readers, and moviegoers that that pacifist Logan finally popped the claws again.

Here’s the latest Logan trailer: