One day in 1991, John Backderf got a phone call that retroactively changed his entire childhood. He learned that a horrifying series of murders had been committed by a friend of his from high school, a kid named Jeffrey Dahmer. Backderf — who goes by the nom de plume of Derf Backderf — is a cartoonist, and in the subsequent decades set out to tell the story of the troubled boy he knew as Jeff, using a mix of his own recollections and research into the young Dahmer’s life. The result is My Friend Dahmer, an acclaimed 2012 graphic memoir that has just been adapted into a film directed by Marc Meyers. On the eve of its debut at the Tribeca Film Festival, we caught up with Backderf to talk about his memories of Dahmer, the people he blames for Dahmer’s crimes, and the time he and Dahmer entered the office of Vice-President Walter Mondale.

What was it like to watch a finished cut of the movie? I imagine it must’ve been an experience.

I just watched it here in the dark in my studio, and it wasn’t as traumatic as I thought it would be. But at the end, I noticed I was drenched in sweat, so I had to go change my shirt. So I guess it affected me on some kind of visceral level.

Were you initially nervous about letting a movie version happen?

Well, I’d been approached before. Marc [Meyers] was the, I think, fourth filmmaker who approached me. Because this book had a long gestation period and a couple of incarnations along the way, I always just blew off the others, just because I wasn’t ready and because the book wasn’t done. I wanted to finish this book and have it as an artifact. And when Marc approached me, the book was done and it was out there, so I wasn’t as nervous about it. And I checked out his earlier work, and I liked what I saw and decided to give him a chance.

One of the things that I find most fascinating is, in the book, your moral stance is pretty clear: Even though what Dahmer did was obviously inexcusable, it could have been prevented if his community had been more proactive. What, in your mind, went wrong in your town?

Well, everybody did everything wrong. My Friend Dahmer is, at its heart, a story about failure. Across-the-board failure. Particularly the adult world. Everybody, either through incompetence or indifference, just let this kid go. And it’s astonishing to me that nobody noticed or said they didn’t notice a thing. The drinking — this kid reeked of alcohol at school. He used to walk around school with a styrofoam cup full of booze. And nobody noticed a thing? That’s just astounding to me. Meanwhile, they’re bringing in public speakers to lecture us on the dangers of drugs. I mean, the hypocrisy of it was, it really made me very cynical at a young age. And I still find that absolutely astonishing. Everybody dropped the ball. And the result was a pile of bodies. And unfortunately, that seems to happen with regularity. I mean, all you have to do is pick out any of the mass killers of the last 20 years. Be it Adam Lanza or the kid at Virginia Tech, or whoever. And you see the same kind of pattern.

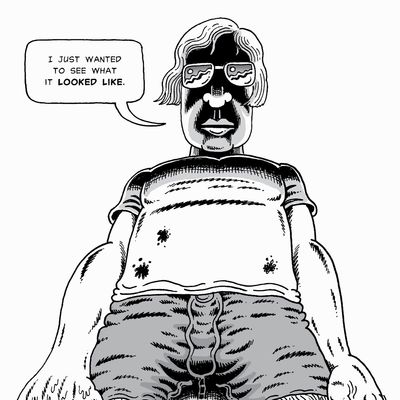

You’re an artist, and you were drawing pictures of him even when you were still friends with him in school. What was visually interesting about Dahmer?

He moved very stiffly. He never seemed to quite fit into his own body or into the world around him. It was kind of a reflection, I think, of his mental state. And obviously the crazy, spastic shtick he had stands out visually.

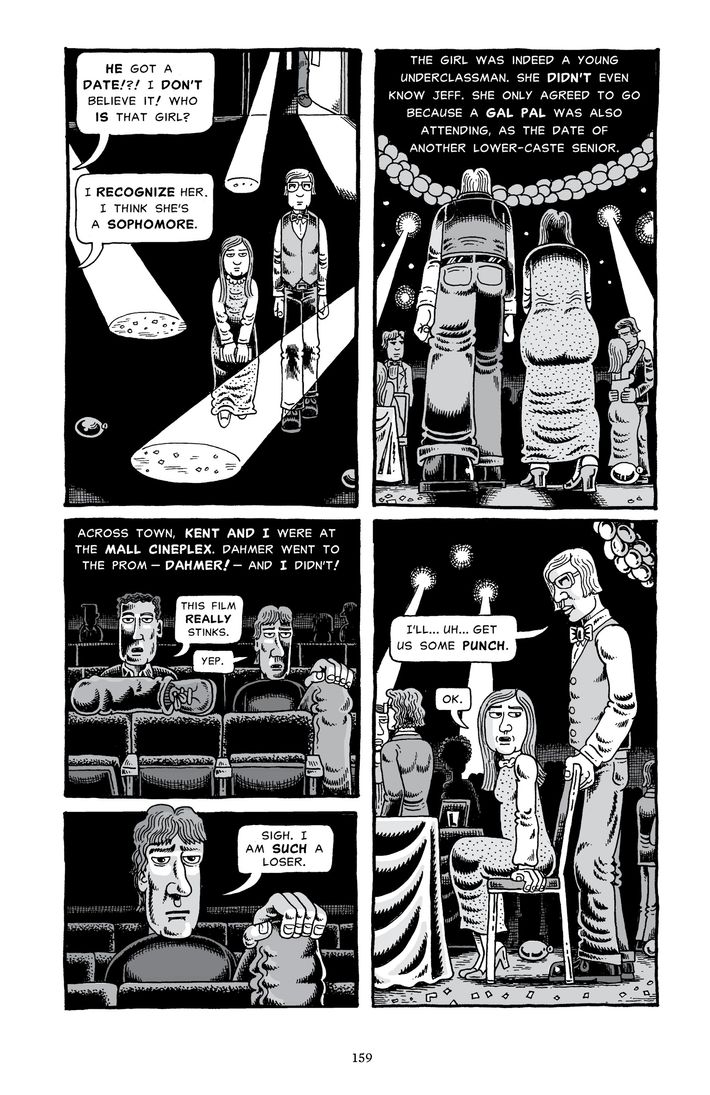

You mention his schtick, where he would pretend to have some kind of mental or physical disorder and spasm and yell and curl his body into weird shapes in public. You and your friends found it funny, but I can’t seem to understand why.

You know, first of all, we were 16 and you’re not. Sixteen-year-olds are morons. I mean, that’s really the only way to describe it. I think when I approached this story, my initial decision was, I have to just be brutally honest in telling this story. So I’ve just got to lay it out there, warts and all. I mean, there’s no defense for our sense of humor at age 16 back then. And I don’t try to make a defense for it. I just say, here it is. I don’t think that most people would be very comfortable with trying to explain their behavior at 16, either. So it’s not something I lose any sleep over. If I was still doing that stuff — like, say, our president making fun of disabled people from the stage — then I’d be a jerk. But I did it at 16, and that was pretty much the end of it. So I’m comfortable with that.

I hadn’t thought about that, but Trump was kind of doing that shtick when he was on stage that one time.

Yep, he sure was. That’s the Dahmer shtick, believe it or not. Yeah, that’s it exactly.

There were a bunch of versions of My Friend Dahmer that you published over the years before the finished version of the graphic novel came out in 2012. What were the origins of the project?

I really started it about a week after he was caught in ’91. I just started filling a sketchbook with remembrances and little factoids. I got together with a couple of my friends, and we all chatted. And I wrote down a bunch of other stuff. And as I was doing that, I realized, Holy crap, this is an incredible story. I’ve got to do something with it. But of course, I didn’t know what at that point. And I really didn’t start working on anything until Jeff was killed. That was ’94 I think.

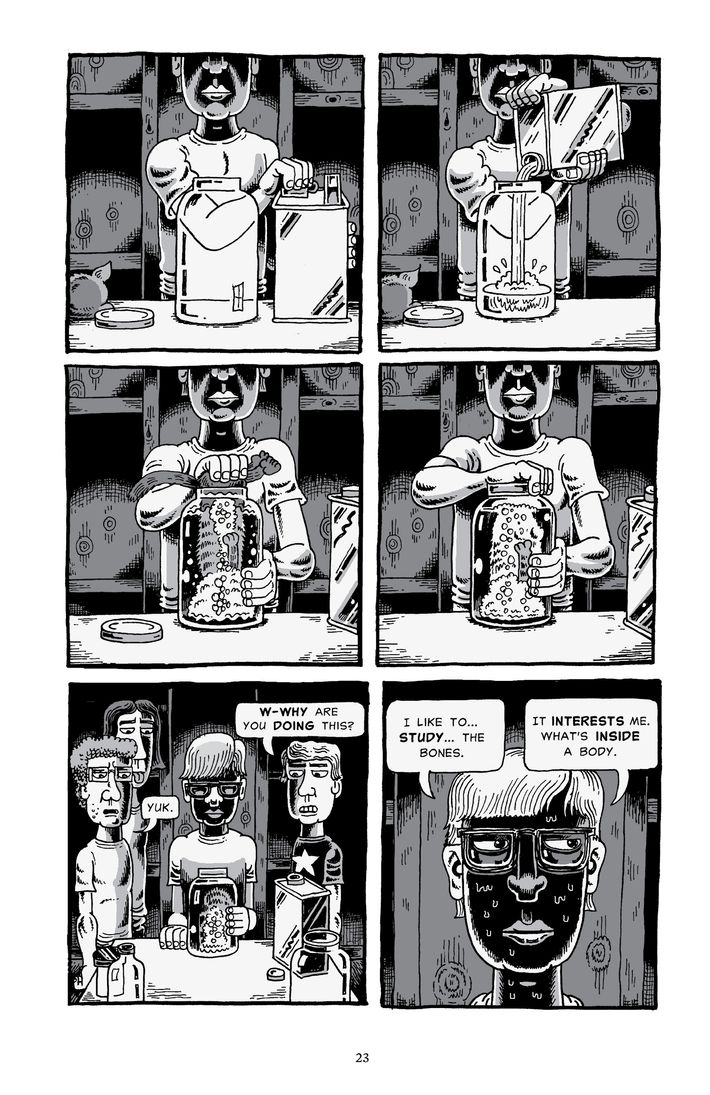

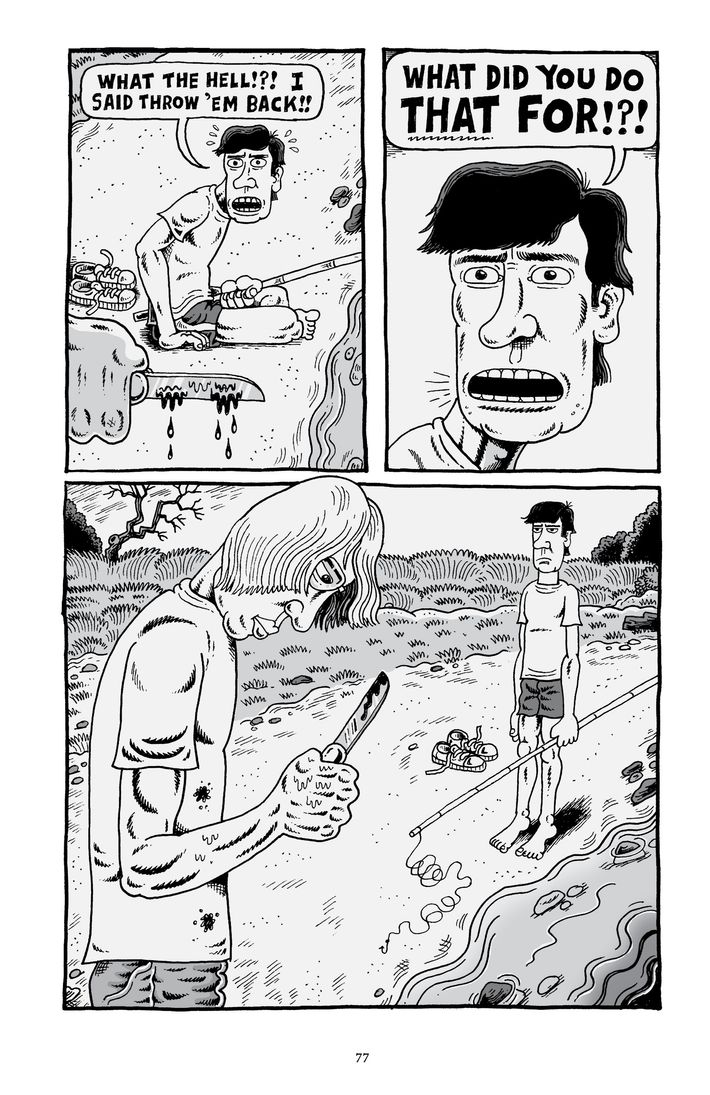

In the initial drawings after you heard about him getting caught, what were they?

Well, I was just trying to remember his crazy shtick and some of the things that he had done. That was like 13 years after high school. One day you wake up and just like that, snap: My entire personal history has been rewritten. We suddenly have this very sinister overlay to everything, this sinister redefinition. We’re like, Holy crap, that’s what he was thinking about when we were doing all this stuff? All these goofy antics suddenly became very creepy. So I had to work on all that, remember all that and write it down with that new definition. And I had a lot of material from that. And then just talking to my friends, because we all carried around things that we’d never really recounted before because they seemed irrelevant or they didn’t really have any point. And then, suddenly, they had a point. All these news stories were coming out, and I started writing those down as well. I had a lot of material.

Had you thought much about him in the intervening years?

Yeah, once in a while. He’d come up, and his name would come up. And it would be like, I wonder what happened to that guy? He just vanished after high school. Just from the face of the earth. No one ever saw him again. There was a very good reason for that, of course, because he had already killed. But none of us knew that. We kind of noted, What happened to that guy? He’s just gone. We heard some rumors that he was in the army and things like that, but that’s pretty much all we heard.

When you’re doing your research on him, were there moments of shock and surprise when you realized he’d done something horrible secretly on a day that you could remember?

Yeah. You know, there were certainly moments, many, many moments where I’d have a revelation like that and my skin would just start crawling. The nice thing is, in taking so long, a lot of those moments had passed. I had all this material, I just hadn’t tied it all together yet. So, at that point, it became a little more interesting, rather than creepy, because it was fun to piece it together and say, Oh yeah, that fits there. This fits there. That process was interesting to me and I guess I just detached emotionally from it at some point.

Were there points at which you went, maybe I shouldn’t be doing this book?

No, it was pretty clear in my head. I mean, it’s Jeff’s story, but it’s also my story. I was a part of it, so I have every right to tell it. And I knew what I wanted to do. That vision was pretty clear from the beginning. Because, remember, the Jeff that I knew had committed no crime. He was just this damaged, dysfunctional kid who spiraled into madness. And I thought that was a very interesting story. So it’s really not about the crime. It’s the story before that story. And that’s the story that I wanted to tell, from the perspective of a contemporary. Because that is what was so unique about the story that I had. So it was very clear. It’s an advantage because I’m not some greenhorn. I’ve got a long body of work. I know what I’m doing by this point, so I was able to really craft it very specifically.

Beyond the fact of how uniquely grisly his crimes were, why do you think America became so obsessed with Dahmer?

Well, I think he flies against the stereotype of a serial killer. I mean, this was a kid from a professional family; his parents were both working professionals. Lived in a nice home, a nice town. He wasn’t living under a bridge somewhere. And he just should have been so normal, and yet he was incredibly, monstrously abnormal. I think that that surprises people. And I don’t get the fascination either, frankly. I mean, I’m kind of at a loss. I mean, I know why I was interested in it because of my ties to it, but the continued fascination with serial killers is kind of a puzzler to me. Honestly.

Have you had much response or interaction with families of the victims? Have people gotten back to you?

No, not at all. I mean, the book is not about the crimes. I mean, it ends, really, the moment he kills his first victim. And the other victims, I mean, that doesn’t happen for another eight or nine years after the end of the book. I know people in Milwaukee [where Dahmer committed many of his murders] aren’t happy about the book, but it’s racked up enough accolades and awards that they can’t really complain that it’s some piece of shit. And I always felt that the book would really kind of take care of any argument. You know, it’s like, read the book. And then tell me it’s exploitative. And you really can’t. So it generally just took care of itself.

Were you involved in the casting of your young self?

No, I was not involved. I wasn’t really involved with the film at all. I was not shy with my opinion, as Marc can probably wearily tell you. But my business is making comics, not making movies. So I really didn’t want to be involved with that. And I just wanted to make as many comics I can in the time I have left. So that’s my focus.

Have you exchanged emails or anything with the kid who played you?

Oh, yeah, sure. Alex [Wolff]. Yeah, he did a great job. All the performances of the young actors are really great. Very, very strong. But, Ross [Lynch]’s Dahmer, I mean, he’s astonishing. But that’s a very meaty role. There’s a lot there for an actor to work with. Playing me, that’s a bit tougher because I didn’t give Alex a lot to work with. But he really shows the important thing: my smart-ass subversiveness. And also that growing disquiet with Dahmer as high school progresses and I get more and more creeped out. He manages to show that in just little glances and body language. Really a very strong performance. He did a super job.

One of the most striking scenes comes when you, Dahmer, and your friends go on a school trip to Washington, D.C., and Dahmer talks his way into getting you all a private tour of Vice-President Walter Mondale’s office. I mean, for Pete’s sake, Jeffrey Dahmer meeting the vice-president — it’s really something. In the movie, he talks to you guys, but in the book, you just see him working in his office. You didn’t speak to him in real life, right?

No.

And you were okay with that change for the movie?

Yeah, you know, there’s a few little changes in the film. It didn’t really bother me. Overall, the film is very true to the book. I mean, there were major scenes in the film that come right out of the book. I mean, almost panel for panel. Which is great. As it should, because the book is very visual. So a few tweaks here and there? That doesn’t really bother me.

How would you advertise the movie to people who are worried it’ll be a salacious and exploitative look at a serial killer?

Hmm. Well, from my own perspective, I’d say, read the book. [Laughs.] Gosh, I’m not sure what I’d tell them. I’d say there’s no killing in it. There’s no real violence at all. That it will surprise you. And that’s really what I say about the book too. It will surprise you. It’s not the story you think it is. You’ll get to the end and you’ll find out that it’s completely a different story than you expected to see. And that’s really all I can do. The reception will take care of itself and that’s already starting to happen. It practically sold out immediately at Tribeca, so the buzz is already spreading fast. And it reminds me a lot of when the book came out. The same kind of buzz. Like, Holy shit. This is really something unusual and unique. And worthwhile. I think the rep will take care of itself.

This interview has been edited and condensed.