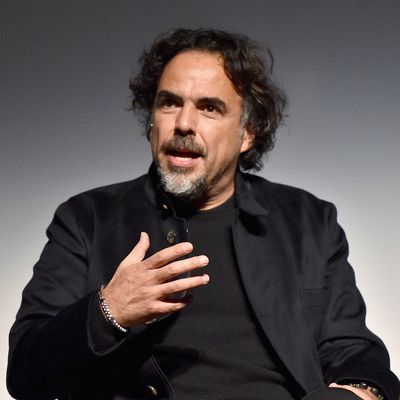

I don’t think Donald Trump would find much to like at the Cannes Film Festival: The current U.S. president is hardly a frequent moviegoer, and all those art films and subtitles would likely prove wearying for him. But there’s one project at this year’s Cannes that’s impossible not to picture through Trump’s eyes, since it’s a virtual-reality experience from Oscar-winning director Alejandro González Iñárritu (Birdman, The Revenant) that places the watcher in the middle of a border crossing from Mexico to the United States, delivered in such a visceral way that it can’t help but shake up what you thought you knew about illegal immigration and its often tragic outcomes. Trump may still seek to build his border wall, but when it comes to this highly charged issue, Iñárritu is determined to dismantle the barriers between head and heart.

His VR experience, titled Carne y Arena, takes place in an airport hangar 20 minutes away from the main seaside drag at Cannes. Viewers are taken to the site one at a time and asked to remove their shoes before they enter a vast room covered in sand, where they don a backpack, headphones, and a VR headset. The six-and-a-half-minute experience then blinks on, and suddenly the viewer is immersed in a border crossing as a group of weary, injured migrants limp through the desert, a fraught scene that is further complicated by incoming helicopters, then the arrival of rifle-toting border guards.

While Iñárritu guides the narrative along through ellipses of time and one unexpected magical-realist sequence, the viewer is free to wander around the expansive setting, following any of the characters as they scatter, hide, and are confronted. It’s hard not to get caught up in the intense nature of the experience: When the border guards order the migrants to fall to their knees and put their hands up in the air, some of the VR participants I’ve spoken to did just that, instinctively cowering before authority. For the first half of my own trek through Carne y Arena, I realized I was playing it too safe, sticking to the outskirts of the setting — like several of the scattered migrants, I was practically hiding behind brush — simply because the clash going on at its center, with barking guard dogs, crying children, and shouted orders, was too overwhelming an aural experience.

But during one dreamlike lull in the action, I shuffled in closer then yelped and attempted to dodge one of the migrants as he came barreling toward me. As he passed through my body like a ghost, I passed through his, too, peering into his insides — heart beating, throat closing — like Leonardo DiCaprio burrowing into the innards of a dead horse in Iñárritu’s Revenant. Draw too close to the border guards, and you can intimately know their hearts, as well. No matter the side, Carne y Arena says, we are all human deep down, and while that could come off as a too-simple platitude in any other context, it’s striking when experienced in this way.

I was affected by Carne y Arena, but the VR portion of the experience is brief and comes with some caveats. Iñárritu shot the landscapes with his Oscar-winning cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, and while I got excited to step into an immersive world filmed by the greatest DP alive, the Oculus Rift doesn’t have that same realer-than-real fidelity that Lubezki likes to bring to his films. Iñárritu asked actual immigrants to recreate the beats of Carne y Arena using motion-capture, but if you get in the faces of their ILM-animated counterparts, there’s a distancing uncanny-valley effect. And while the experience ended on a profound note as the immigrants vanish with only their scattered shoes and an abandoned Hello Kitty backpack left behind in the dirt, I initially thought Carne y Arena was over too soon.

But then came the coda. After the attendants took off my visor and headphones, I left the room and wandered down a long, dark hall with video portraits of the real immigrants (and even one border guard) installed every few feet. As they stared back at me, the particulars of their journey were overlaid on their faces, the stories assembled from interviews into first-person prose. There was no sound in the hall except for the strangled sobs I made while reading, in their own words, how they had weathered the terrifying circumstances of the border crossing. Had I read these testimonials in an article, I would have been moved by what these people described, and sickened by the ordeal they went through. But to encounter these stories after Iñárritu’s simulation made me a witness of sorts, which gave the immigrants’ testimonials an additional, undeniable power that I still haven’t been able to shake. When it comes to high-resolution fidelity, virtual reality can’t yet measure up to real life. But when VR is put to its greatest use, it can do what the best of cinema does: It sends you out into the real world, ready to look at it in a whole new way.