Fifty years ago this week, a young London kid named Geoff Emerick was hearing — from what must have seemed like every passing window — the fruits of an odd project he had been an intimate part of over the previous five months: the recording of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band.

As an apprentice at EMI’s Abbey Road Studios, he had by chance been assigned to the studio where a producer named George Martin listened to four young Liverpudlians present their first songwriting effort: “Love Me Do.” As the years went on, Emerick watched the band record “A Hard Day’s Night” and other early hits, and then, as a full engineer, took on a major role in the creation of Revolver, Sgt. Pepper, Magical Mystery Tour, part of the “White Album,” and Abbey Road.

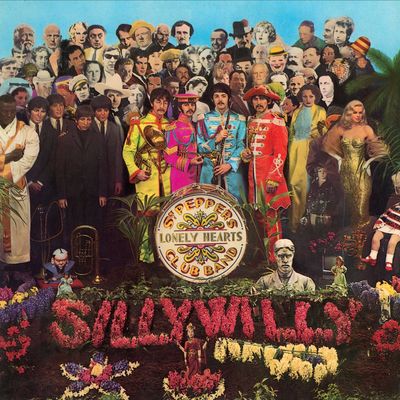

As we hit the 50th anniversary of Sgt. Pepper, the Beatles organization, which has never met an anniversary that it couldn’t produce some rejiggered product for, has put together what must be the ultimate Sgt. Pepper reissue — six discs, in a big ol’ box with lots of added swag. (There are also numerous smaller packages available.) There are several discs of outtakes, two Blu-rays with audio and remastered promo films, and remixed stereo and mono versions of Sgt. Pepper.

The reissue is produced by Giles Martin, the son of the famed Beatles producer George Martin; the two worked together on the extravagant mash-ups of Cirque du Soleil’s Love. (George Martin died last year, at 90.)

While Emerick has done his time working on Beatles-related material in his latter career, he didn’t have a hand in this reissue, and said he hadn’t heard it yet.

Fans will drool over the packaging, and approach a new set of remixes with trepidation. After all, there is still no clear set of intentions: Do you make the record sound the way it did in ’67 through today’s technology? Or you do what the Beatles would do, were they working today? Do you make it sound — gulp — better? Or just more Sgt. Peppery?

The easy stuff — like the little shouts in the opening bars of the “Sgt. Pepper” reprise — were noticed and tweaked long ago. But to my ears, particularly on the stereo mix, the sound on the new set is harder and edgier, but also fuller and more pronounced, which I’m sure was the remixers’ intention. Ringo Starr has been quoted as saying he loves the bigger drum sound. The down side is that the “more pronounced” part is an aesthetic decision that in effect overrules the Beatles’ original decisions. I’d like to hear from other sets of ears, but “Within You Without You” now makes me feel a bit like I’m being aurally poked, rather than being lulled into a reverie. I also think that on quieter songs some atmospherics may have been too far reduced, like on “She’s Leaving Home.” (It’s like when you see a redone version of a ’70s film and the graininess has been taken down.) In listening to myriad reissues through myriad systems, I was surprised that the 2009 reissues played on Spotify through a Sonos sounded about as good as anything else.

Anyway, Emerick was the point man as Martin and the Beatles worked to create new sounds in the studio, doing everything from moving microphones to rewiring building electronics to manipulating tapes. Emerick’s book, Here, There and Everywhere, is a sober look at the day-to-day decisions and the absurd bureaucratic wrangling behind these famous records. The fabled studio was in reality a cold place, with unadorned walls, a few folding chairs, and little patience for the nonsense known as rock and roll.

In fact, one of the key subplots is the tale of how the band and its production staff daily suborned the recording rules at EMI. This was the preeminent recording operation in the world, and was run more than a little bit like IBM, with a strict hierarchy of staff: technicians in white coats, engineers in suits and ties, and obsessive enforcement of recording protocols. (In early years, the band even found milk for tea unavailable after hours; the refrigerators were locked.)

Then came the Beatles.

As was the case with the group itself, it’s not an entirely happy story. Emerick quit in disgust as the band feuded while recording the “White Album,” but came back with Martin to handle Abbey Road. After the ’60s, Emerick went on to a distinguished career behind the board, working on everything from “Stuck in the Middle With You” to Robin Trower to Cheap Trick, from the Zombies to Art Garfunkel to Chris Bell — and stayed in touch with Paul McCartney, among other things participating in the idiosyncratic trip to Nigeria to record Band on the Run. (And Elvis Costello fans know that he produced Costello’s distinctive 1982 masterpiece, Imperial Bedroom.)

Emerick, who turned 70 last year, was kind enough to take some time to reminisce with us.

At this point there have been several generations of people who have come to know the Beatles. If you were talking to someone, say, in their 20s who was interested in music, how would you tell them to listen to Sgt. Pepper to appreciate some of the things that are going on?

I guess the first thing would be to listen to the arrangements of the songs. They used to come into the studio with the song written, but without having an idea of what the instrumentation should be, and then we would, like, rehearse it for a few hours with certain instrumentation, and if it didn’t work out, we then changed the instrumentation whereby the piano might now turn into a harpsichord and so forth.

And so while we were doing this, if someone made a mistake or played a dissonant chord or something a bit weird, then they might like it. So we used to embellish the mistake.

And of course, we were on 4-track and not a 120-track like now. We had to make decisions and put all the right sounds on at the time of recording. Then we moved onto the first overdub, and then we’d know whether it fit or not. It was making decisions and so forth, not like doing 120 tracks and say, oh, we’ll do it on the mix. We didn’t do it on the mix.

Is it true that Paul McCartney always wanted his bass a little bit higher?

Yes. I started really young. I was like 19 when I started to record the Revolver album, and I knew them because I’d been an assistant engineer on some of the singles, like “She Loves You” and the Help! film and so forth. [I had ended up as] a mastering engineer. We were remastering American records for the European market.

So I used to get American records in, and I realized at that point there was a lot more bass on those American records than what we were allowed to put on our records at Abbey Road. Paul and I had many discussions about that, and then I tried to not break the rules, per se, but experiment. We didn’t have selectable frequencies, so I could only add more bass from the board. It was just bass and treble on the mixing console. So if I wanted a little bit more bass or whatever, I’d have to just adjust [McCartney’s] amp.

We wanted more bass on the records, and it was a bit of a fight. In the instance of “Paperback Writer” and “Rain,” I used a loudspeaker as an experiment. My theory was that if, you know, the loudspeaker can push the bass out, then maybe another speaker can take the bass back in, and I used the speaker as a microphone. So we were always striving for good quality bass on the records.

As a comparison, the average person’s car radio these days has much more powerful equalization powers than you did in the greatest studio in the world at the time?

Yes, that’s true.

What I love about your book, Here, There and Everywhere, is the portrayal of Abbey Road. I never quite got how much like a widget factory it was. It must have been like working at IBM, with so many strictures and people wearing lab coats and coats and ties, and this extraordinarily strict hierarchy.

Yeah, it was. The studios were classically orientated. There’s a classical side and a pop side, and the classical people looked down upon the pop people, although it was the pop records that were making the money to pay for the classical sessions, you know?

So you, as a young lad there, I guess you’d say, you came into work every day with a coat and a tie?

Oh, yeah.

And you basically didn’t look cross-eyed at anybody who was one of your superiors?

Oh, no.

I was also amazed to hear that, considering the technical wizardry that was there, that you said that sometimes you’d be overseeing a tape deck that was basically a floor away and down the hall in a little windowless room. How did something like that happen? Why was it so jerry-rigged like that?

Well, there were three studios and only two 4-track machines, so it was patched through from a maintenance room where they could actually plug all the 4-track feeds from whichever studio up into the 4-track rooms. So 4-track room number one would be linked to maybe studio two, which was next door, but it could also be linked to number one studio, which was down a level, and then number three studio was up at the front.

Except when we started to do the tracks on Revolver we had to have the machines in the console room, because of the complexity of what we were trying to do. We might have to just drop a guitar maybe onto a vocal track, because of the track limitations. We wanted the machine in the control room in case something got whacked in the vocals as we’re dropping the guitar in. There was a discussion between the hierarchy of technicians, and it was deemed that it was not a very wise idea to wheel the 4-track machine down the corridor.

But they eventually did agree to do it, and there was like a little team of people sort of watching as the brown coats, as they were called, who did the moving of pianos and so forth, wheeled the machine down the corridor, and they were all following them to observe what was happening. Then there were discussions about lifting the machine over the threshold of the door. A lot of importance was given to everyone’s job I guess. So, eventually, we did end up with the tape machine in the control room, and that was a first.

So when you say you put a drop-in of a guitar onto a vocal track, you’re superimposing it almost like a double negative in a photographical sense?

Yeah. We would have to put the guitar on the vocal track, for instance. Not that we really wished to. So, normally, it would go on the normal guitar track or whatever, but you know, we’d got no more tracks left. The vocal track might be only track where there’s a gap at that point with no vocal on it. So that’s where the guitar goes.

Wow, and would you physically play the vocal track, and then the musician would play the guitar at the right time, and you’d physically record onto the actual track?

Yes. So the vocalist stopped singing, and then that’s where the guitarist is going to do his solo, so the person who’s operating the tape machine then puts that particular track into record and records the solo, and then stops recording when the vocal is gonna come back in. The soloist knows that he’s got so many bars to do his solo in.

I’m recording this interview on GarageBand, on a Mac. I could record Sgt. Pepper on this, right, with no problem?

Yes. [Stops himself.] I don’t know…

No, not the talent! I mean, physically. I could do more than Sgt. Pepper, right? This thing has an unlimited number…

Oh, absolutely. Yes, of course you could.

“Strawberry Fields” was part of the Sgt. Pepper sessions. There’s an interesting cymbal sound, and my understanding is that’s a reverse cymbal. How physically did you get that onto the tape?

Well, it was just recorded onto a separate piece of stereo tape — or mono tape, really, because we weren’t really thinking about stereo. It was recorded onto a piece of quarter-inch mono tape as a forwards recording, and the tape was spooled to the end. It was then turned over and played, and then of course it was playing backwards. That was injected into the 4-track.

With none of this computer synchronization or anything like that, right? You’re doing everything by hand?

No, absolutely nothing. We didn’t use click tracks, either, then.

How much physical cutting of tape was there?

Not a lot. Except on “Strawberry Fields,” you know. There were two different recordings of it. We’d done the first version, and John was sort of fairly happy with it, and then he came back about two weeks later, and he said, I want to re-record it again. I want it to be a bit more aggressive, and I need musically different instruments added to it. That was then the second recording.

He came back about another week later and said, “Well, you know, I really like the first half from the first recording and the second half from the second recording.” The problem then being that they were different keys and different tempos. George Martin had basically said to him, “No, this is really impossible.” But “impossible” and “no” did not exist in the Beatles’ vocabulary. John said, “Oh, come on, mate, you can do it, right?”

What we did, we put them on two separate tape machines, quarter-inch machines for playback, and put those machines on varied speed, which means you can alter the speed of the tape. You could speed it up or slow it down.

We had to find our editing point where we thought we’d join them, which was on the word “going,” which is about a minute into the song. So we’ve got the second version lined up on the tape machine on a certain speed, with the first version [sped up] to come up to tempo with the second one. The idea was to gradually speed it up so you can’t hear it.

By altering the speed, we brought them into the same key as well. Then, we knew where our edit point was going to be. We used scissors in London. They didn’t have razor blades and blocks because of all the classical editing, where they found that using scissors [was better]; they could adjust many angles for special edits on classical recordings and stuff.

So what I did, I had my little brass scissors. Normally, an edit would be like a 45-degree angle cut across the tape to join them together. In this occasion, it was a very sort of shallow, long sort of angle, like what we’d call a cross-fade. I put the editing sticky tape over the edit where I cut it, and then John came up to listen to it.

He went down the stairs into the studio down into number two, and it actually worked! And when he came up, I stood in front of the tape machine so he wouldn’t see where the edit was, and he couldn’t hear where the edit was. So it was perfect. It was just magic at the time.

So many Beatles songs that you hear someone else play, or when you see Paul McCartney live, they don’t quite sound the same. Part of the reason I think is because of all this tape manipulation in the studio. Is it true that sometimes you’d tape people’s voices slower and then speed them up for the actual recording?

Yeah, sometimes we would. It’s just to get a different sort of tonality on the voice. Otherwise, all the voices, they’d all sound the same all the time. We did it with harmony voices sometimes. On “When I’m Sixty-Four,” we sped that up to make Paul sound a bit younger.

That takes a lot of meticulous work on both sides, right, to hit all the beats correctly without the click track?

Well, they were very good as timekeepers. So that we never needed click tracks. What normally used to happen then, because of the lack of click tracks, when you got to the chorus of a song, the chorus would have a little bit more energy, and the tempo would gradually go up. I know you can program a click track today to be able to speed it up at the chorus point, but then it was just human energy, transferred into the rhythm of the song. That’s why a lot of those records sound so exciting.

One of the great things about the Beatles is that, despite all the technology, it’s not a fight. It’s just a balance or a great melding of the human, and the organic, and the technological.

Yes. We also had the luxury of time. They might come in with a song and we’d spend four hours on instrumentation for it and then change that instrumentation because it wasn’t quite working out. In the meantime, I’m trying to alter the sounds of the guitars in some way, or the drums in some way, or the piano in some way. For one song, I might mike the piano from the top. Then we’d realize the next song’s like a little bit moodier. So I wouldn’t want a bright sound on the piano, so I might mike it from underneath the piano.

Is that’s what gives those songs their peculiar feel?

I’m like painting a picture with what I’m given from the studio. It’s like a canvas, you know, and structuring it that way, it’s hard to explain it, but that’s how I see it.

Do I remember from your book that someone put thumbtacks on the piano hammers to give the piano a slightly more metallic feel?

No, that was an upright piano, and it had little metal tips on the ends of the hammers. That was something you could actually buy. It was called a tack piano. There were a lot of other little keyboard options. There was a Steinway upright that was tuned out of tune.

Was that the piano on “Lovely Rita”?

You’re talking about the solo? They were stuck for [an idea] and without, you know, making myself sound good, I said, “Well, why don’t you do a piano solo?” Because they were really stuck. I was standing at the top of the stairs, and they said, “Well, you come and play!” Being so young and nervous, there’s no way I was going to do it. [George Martin himself ended up improvising the jaunty solo.]

I knew a regular piano sound wouldn’t sound right. It needed a sound on it, a color, per se. If you listen to it carefully, the piano went into an echo chamber, but the signal that went into the echo chamber went via a tape machine, and I put sticky tape all over the guide rollers of the tape machine.

So the guide rollers had the tape wobbling all over the place. I mixed that in behind the real piano sound with a lot of treble. So that’s what the sound is on that piano. And today you could actually get that as a [digital recording] plugin.

To go back to the organic thing, one of the great stories in your book is when you described the band doing the reprise of “Sgt. Pepper.” I’ve always thought that’s a thrilling track. The reprise was played by the four Beatles, two guitars, bass, and drums, live in the studio?

Right. They were going away on the Monday or the Tuesday of whatever week it was, so there was a desperate rush to record the reprise. The only studio that was available was number one studio, Abbey Road. Someone else was working in number two. Number one studio is really cavernous. So what I did, I got a lot of sound baffles and made like a little room. I had them all very close together and as you know, you hear all that energy come out of that live take. You hear the emotion, you know?

I’ve always thought the piano track in “Day in the Life” is extraordinarily moving. Is that crazy?

No, that’s not crazy at all. John was a brash sort of a rough-and-ready type person, and where Paul was like the romantic, and that was a great combination of the two of them. Sometimes, as John got round the vocal mike to sing a song, especially “Day in the Life,” there’s all this sort of emotion and stuff that came out of him, which you don’t see when he’s just not singing and just being a normal John. I thought, “How does he get all this feeling and emotion into the way he sings?” It was many years afterwards, I’m thinking, he was just thinking of his childhood.

That must’ve been something to hear him sing those vocals.

When we first lifted up the faders in the control room, we had shivers running down our backs. “Day in the Life,” that’s just the best thing ever.

Can I ask you a question about Imperial Bedroom? Was that an important record for you?

Oh, absolutely. I loved Elvis, and I always wished his voice was louder. When we started recording it, on the monitor side of the mixing console, you know, I had his voice really far forward, and I put a Fairchild 660 limiter on his voice, which really brought it way up front. It took him a while to come to terms having the voice that loud in a mix. But I saw him last year, at the jazz festival in New Orleans, and I was discussing it with him. I hadn’t heard Imperial Bedroom for a while, but I was listening one day, and I was listening to the ends of the words when he was singing.

Because of the volume of the voice in his headphones as he was singing, he was actually crafting and sculpting, like, the mouth noises on the very ends of the words, tonality wise. I said, “I heard that.” And he said, “Yeah, you’re right.” That’s what I was doing. It was very spontaneous, and I recorded it in sort of an old-fashioned way, and I think most people were working at 30 inches a second and I think I recorded it at 15 inches a second. I didn’t want it to sound hi-fi. That was my thought there.

And what effect does that have on the sound?

What you hear is the bass is a bit different, and the high end’s not as bright. It’s just more raw, let’s put it that way.

This interview has been edited and condensed.