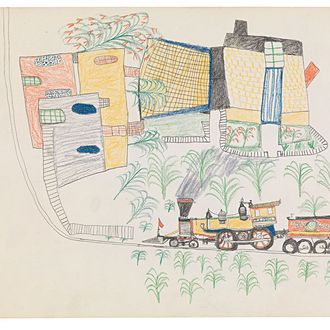

A great work of art from 1875 never seen in any museum, almost never seen at all, and all but lost to history, sat radioactive on the wall of a small gallery at the recent Frieze New York art fair. A simple depiction in prismatic hues — pencil and lustrous color — somehow expressed a thousand anxieties, lost freedom, emotions secreted away, omens of anger, empty worlds, tears, and the life of a captive. We see a canary yellow locomotive pulling a decorated red coal car and an invisible payload moving in an 1875 landscape of fields of corn, front yards, wooden fences, towns, buildings, and tracks, all running through the back of America’s memory. This is the end of the journey of 72 Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Kiowa prisoners of war found guilty without trial and all taken south and east away from their native lands of eastern Colorado, western Kansas, northern New Mexico, Oklahoma, and the Texas panhandle. Removed from a region that once teemed with herds of wild horses and bison and the traditional Plains way of life, they were piled on horse carts, ships, and train and brought to a prison camp at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida.

The artist is Bear’s Heart, one of the 72 prisoners on that fateful forgotten train. Once the captives reached Fort Marion they were subjected to rigorous military discipline and forced labor. However, to please visiting tourists the prisoners were also encouraged to draw. Thus, like prisoners everywhere, these artists found coded ways to depict their captivity. The picture gives us an instantaneous spatial and emotional estuary of warring integrating opposites. The vantage point of the drawing flips from frontal and straight on — the left being the bottom of the image with the tracks turning right, to an overhead depiction of a planted field and fences curving in every direction. This is also the last lost moment of life outside camp walls, with color, a sense of life in the world, a world that is enjoyed not endured. The thought that the person who made this paid with years of his life for the “honor” of creating it drills into my heart.

In other drawings, the 24-year-old Bear’s Heart depicted Cheyenne cosmology, dragonflies, and butterflies. For millennia it was imagined that art could heal wounds, be a balm to history, defeat, death, and loss. In our museums we feel this. But we cannot know this with Bear’s Heart’s gleaming hellish drawing. This is because almost none of the many great ledger drawings made in this period have ever been integrated into any museum permanent collection of this period. I think it could go up against anything made anywhere in 1875. And should. Soon. As for Bear’s Heart, he soon settled at the Cheyenne-Arapaho Agency in Oklahoma in 1881, where he died of tuberculosis the year of his 30th birthday.

*This article has been expanded since its original publication. A version of this article appears in the May 29, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.