At the end of the exhibition “Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World” there is a small room that sits at the top of the Guggenheim’s ramped white rotunda. The room is marked “Coda,” and visitors arrive to it after viewing artwork by artists spanning more than two decades of practice. There are only three works in the room: an installation by Gu Dexin, an ink painting by Yang Jiechang, and a video piece by the couple Sun Yuan and Peng Yu. Of the nearly 150 works included in the show, the last piece, titled Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other, has attracted by far the most attention. It seems possible that without the inclusion of this piece, the show might not have been the subject of significant public outrage.

Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other documents a performance held in 2003, where eight dogs identified as “American pitbulls” were escorted by private limousine into an art space in Beijing and placed on treadmills facing one another. They were strapped in place, able only to run forward. After the New York Times published a preview of the exhibition, pet owners and animal-rights activists immediately took notice and began circulating petitions and social-media campaigns calling for the removal of Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s piece, as well two others involving animals, by Xu Bing and Huang Yong Ping. A change.org petition accusing the museum of displaying animal torture as art racked up more than 750,000 signatures, and the museum seemed caught off-guard by the intensity of the criticism. Only five days after the Times preview appeared, the Guggenheim announced they would not display the three works as originally intended, citing “concern for the safety of its staff, visitors, and participating artists.” For Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other, this means the screen of the television is frozen on the video’s title card in a compromise decision to physically include the work, but not the parts that were offensive. Animal-welfare activists were disappointed that the museum had not conceded that the works amounted to animal torture, and critics elsewhere noted that the manner in which the museum responded to the controversy closed off the possibility of any substantive engagement around questions of violence, animals, and the display of art.

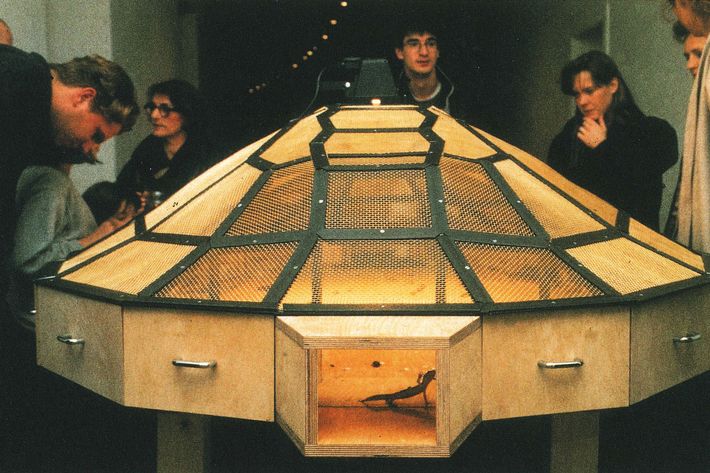

To be clear, the video piece by Sun Yuan and Peng Yu relies on the use and abuse of animals. So do the two other works that were protested: Xu Bing’s 1994 video A Case Study of Transference features two pigs mating with gibberish Roman letters and Chinese characters tattooed over their bodies, while Huang Yong Ping’s Theater of the World, which the exhibition takes its title after, planned to stock a cage shaped like a tortoise’s shell with live insects and reptiles. Animals including African millipedes, Goliath beetles, hissing cockroaches, stag beetles, leopard geckos, and Italian wall lizards were intended to live and die in the same space, and often at each others’ hands — not too unlike anything that happens in homes with pet reptiles. At least two additional works in the show depict violence against animals, but escaped notice by social-media activists: Wang Xingwei’s 2001 painting New Beijing, in which penguins shot in the chest stand in for wounded protesters at Tiananmen Square, and Liu Xiaodong’s 1998 painting Burning a Rat, of two idle men who set a rat on fire for amusement. It can also be assumed that still other works in the show were created using animal products and byproducts, a situation that would not be unusual to any particular exhibition of art.

Was it necessary to include these works in the exhibition? For many reasons, yes. Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other and the other works included are, for one, impossible to separate from the context they were created in. Ben Davis has written an excellent commentary for Artnet on the subject, noting that the artists work within a genre of installation and performance art noted for its brutality and macabre spectacle. “Critics, both inside and outside of China, have often read the nihilistic extremes of Chinese performance and performance-installation from this period as morbid symptoms of a society wrenched by stunning change combined with a lack of any sense of political control,” writes Davis. Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s performance-installation work comes at the tail end of a post-Tiananmen-to-new-millenium period of art practice, in which many artists were reconciling with the breakneck social changes — from globalization to urbanization — and trauma that were a byproduct of the country’s integration into a neoliberal world order. Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other is Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s commentary on the competitive, often exploitative structures of sport and commerce that felt most relevant in 2003, just two years after China entered the WTO and Beijing won the bid to host the 2008 Olympics.

The controversy is also impossible to separate from the differing sociocultural and legal frameworks that buttress attitudes toward animals in China and the United States. In this case, an American understanding of animal rights that is largely defined around our relationship with our pets came into conflict with art from a time and place that does not share the same understanding of the relationship between animals and humans. Some chalked up the use of animals to an indifference toward animal life somehow specific to Chinese culture. (It’s especially telling that social-media campaigns primarily reproduced images from Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s video work featuring dogs.) But what’s missing from the conversation around Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other is that since 2003, the context for performance installation in general, and Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s work specifically, has decidedly shifted. A growing number of Chinese count themselves among the animal-rights movement, and there have been two attempts within China to introduce animal protection laws. As China’s urbanization deepens and spreads, a greater number of households own pets. Sun Yuan and Peng Yu have not staged major works featuring live animals in the last decade.

More important, though, the violence and coercion enacted upon animal bodies is part and parcel of the violence and coercion that defines the entire show. Returning to the final room of the exhibition, “Coda,” Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s Dogs that Cannot Touch Each Other sits in the furthest corner of the space. The room is otherwise dominated by the two other works of art in it: an ink painting by Yang Jiechang, Lifelines I, which depicts the paths taken by volunteers carrying away the bodies of the injured on Tiananmen Square the night of the massacre, and an installation by Gu Dexin which covers the four walls of the room in bold red Chinese text. It reads, without punctuation:

We have killed people we have killed men we have killed women we have killed the elderly we have killed children we have eaten people we have eaten their hearts we have eaten their brains we have beaten people blind we have beaten open their faces

The room is a profoundly dark note on which to end an exhibition that also begins in 1989. To the extent that the show surveys art and society in China from 1989 and on, the “Coda” asserts that the night of June 4, 1989, remains the defining event of these times. It is a deliberate curatorial choice both to start and end the exhibition on 1989, and one that is obscured by the public focus around animal rights. For what was the Tiananmen massacre if not a trauma of China’s transition out of socialism and into neoliberal world order? The exhibition had always been intended to be about the effects of violence and brutality on art and society, and the works selected for the show — including those involving animals — embraced that difficulty.

Before the social-media outcry, the Guggenheim seemed to understand this, and were prepared to defend Huang Yong Ping’s work in particular, given that it was originally meant to anchor the show. In an interview conducted prior to the exhibition’s opening, lead curator Alexandra Munroe told Artnet that “We wanted to open the show with [Huang Yong Ping’s Theater of the World] because … it introduces the visitor to an artist’s thinking that is embracing chaos, that is filled with questioning, that is atheistic, that is fearless of any governing ideologies, that is asking tough questions, and that is brutal.” Referring to central space in which the work is installed, Munroe cautioned viewers, “If you can’t survive the high gallery, don’t bother seeing the rest of the show. The work in the show is intense.”

Ultimately, any exhibition purporting to represent important art from China during the last two decades needs to address the themes represented in works by Huang Yong Ping, Xu Bing, and Sun Yuan and Peng Yu. The museum’s inability to control the narrative surrounding its own exhibition speaks to both a missed opportunity for a larger, more nuanced conversation, as well as an inability to make the exhibition intellectually accessible in a media landscape of fake news, memes, and social-media campaigns. When the museum reluctantly announced it would be altering the display of the disputed works, it fell back on what is by now a tired and conservative defense of “freedom of expression”: “As an arts institution committed to presenting a multiplicity of voices, we are dismayed that we must withhold works of art,” they wrote. “Freedom of expression has always been and will remain a paramount value of the Guggenheim.” It’s a conclusion that misses the larger point. Today, both the Guggenheim and the artists featured in “Art and China After 1989” have plenty of access to artistic expression, even an abundance of it, and serious challenges to an artist’s ability to express themselves through exhibition are usually fiscal. In the end, what’s at stake is not the freedom to display animal torture as art, but whether or not the museum is still a site for staging difficult conversations around difficult works of art.

“Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World” is on display at the Guggenheim through January 7, 2018.