I pledge allegiance to Oscar Wilde. Evidently, David McDermott and Peter McGough do, too. The collaborative duo and longtime art-world treasures are kindred Wilde spirits, and their reverence is clear in their transforming installation, Oscar Wilde Temple, 1917. This enchanted mise-en-scène is devoted to the tragic last chapter of Wilde’s life — his trial and imprisonment for homosexuality, followed soon thereafter by his death in exile in 1900. The installation, which was lovingly curated gratis by Alison Gingeras, is an actual chapel housed in the Church of the Village across the street from and staged in collaboration with the LGBT Community Center across 13th Street. See it. Art that wittily but unironically traverses heartbreak, spiritual violence, social injustice, love, and cries against hatred is rare. I wish it could remain here forever.

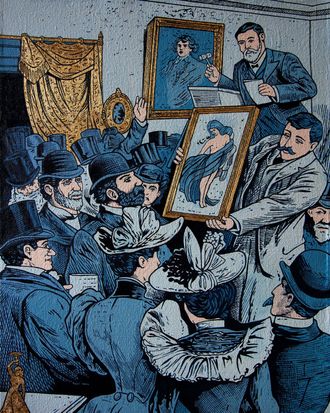

Visitors open a door and enter a dimly lit basement room that has been lovingly done up as a solemn, serious, hushed Victorian-era Aesthetic Movement chapel. The installation is as effective as time travel. There are specially made fabric wall coverings, a votive candle stand, wooden chairs, and more. On the walls are small paintings made by the duo, depicting scenes including his 1895 arrest for “sodomy and gross indecency;” Wilde pleading not guilty in court and uttering the famous phrase “the love that dare not speak its name;” we see him being convicted and sentenced to hard labor on May 25, 1895, as the judge cries that “this is the worst case I ever tried” as Wilde protests “And I? May I say nothing, my Lord?” as he’s drowned out by shouts of “Shame!” Peter McGough called the cycle a “stations of Oscar Wilde to Reading Goal,” the prison just west of London where Wilde was incarcerated. Lest you mistake the artists’ intentions, Wilde is portrayed with a halo. There are also small circular images of more contemporary gay martyrs of “homophobia and the AIDS epidemic,” including Alan Turing, Harvey Milk, and Marsha P. Johnson, an African-American transwoman sex-worker activist who played a key role in the Stonewall uprising, which took place just blocks from here in 1969.

At the front of the chapel is a sort of centerpiece. There, behold a four-foot-three realistic figure of Wilde beautifully carved in linden wood. It is based on an iconic image made of Wilde by photographer Napoleon Sarony in 1882 in his Union Square studio a few blocks from here. The statue rests atop a pedestal on which is a diamond-shaped black, gold, and gray plaque painted with the number C.33. This was Wilde’s prison number and name at Reading Jail.

For anyone familiar with Wilde’s last chapter there’s no way not to be moved by the earnest love on display here. For those unfamiliar with this story, not only does the chapel provide an opportunity to learn about it, but the 117th anniversary* of Wilde’s death falls this month on November 30. That’s today.

Allow me to retell some of that story based on Richard Ellmann’s indispensable Wilde biography — until reading this book I thought that no one had ever had more psychic pain inflicted on them than the characters in Proust, who suffer endless internal agonies and obsessions. Ellmann demonstrates that the internal and physical brutalities inflicted by England on Oscar Wilde make Proust look tame. First there were trials for “indecent acts,” public humiliation and abuse, then two years of being incarcerated, sentenced to hard labor, in three different prisons — each more hideous than the last.

While in jail, Wilde, perhaps the most talkative person who ever lived, was not permitted to speak a word. Ever. For two years. Not once. Perpetually starved and underfed, when he was fed it left him simultaneously malnourished and suffering from nonstop dysentery and diarrhea. English prisons did not have plumbing. Each prisoner was given a tin cup and forced to sleep in his own feces. Wilde’s bed was a narrow, upwardly inclined wooden plank set an inch or so from the cold stone floor. He had no mattress or blanket and suffered the further torment of permanent insomnia. Pen, pencil, ink, and paper were not permitted.

For these two years, once a week he was allowed 15 minutes outside his solitary confinement, during which he was forced to walk in circles within an enclosed brick courtyard with no view outdoors. Once, another prisoner spoke to Wilde, saying, “your sort” shouldn’t have to suffer this kind of punishment. It was the first pity Wilde experienced in more than a year. He began to weep, said, “God bless you.” He was punished for doing so. He was released from prison a broken old man, having served every single day of his sentence. He died two years later at the age of 46.

McDermott and McGough remind us that any society that breaks a person this way is itself broken. At a time when the voting-, civil-, trans-, and gay-rights clock is being turned back, and the American prison system is dysfunctional, this little chapel imparts some of what it means to make oneself as vulnerable as Wilde did. Not just resistance. But rebellion. Revolt. Here, we experience things more than merely philosophical and ideological, and can be shaken awake.

* This post incorrectly stated that today is the 217th anniversary of Wilde’s death. It is the 117th.