Over the course of a 15-year career, Maroon 5, the million-selling pop act, have released just one single featuring a rapper or R&B singer. So it was surprising when, in the lead-up to their recently released album Red Pill Blues, they put out four such singles in a row.

Or maybe not. “The demand for urban collaborations on pop releases has been at an ultimate high,” says Chris Anokute, CEO and founder of Young Media Inc., a management and A&R consulting company, and a former major label A&R for Capitol, Island Def Jam, and Epic Records. “I haven’t seen anything like it before.”

This year, though, a lot of these collaborations didn’t work. Neither Katy Perry’s “Bon Appetit” with Migos nor “Swish Swish” with Nicki Minaj made it into the Top 40. Jason Derulo’s “Swalla,” with Nicki Minaj and Ty Dolla $ign, is the lowest-peaking lead single (No. 29) from any album he’s ever released, by a wide margin. Selena Gomez’s “Fetish” with Gucci Mane is her lowest-peaking single to have registered on Billboard’s Pop Songs chart, which tracks radio play on pop stations, since 2010. Zayn’s “Still Got Time” with PARTYNEXTDOOR topped out at No. 66 on the Hot 100; Lorde enlisted the services of Khalid, SZA, and Post Malone to juice “Homemade Dynamite,” but only reached No. 92. (All chart positions are based on U.S. sales and streams only.)

Electronic producers who enjoyed years as mainstream pop fixtures have hit a similar wall when incorporating rappers and R&B singers on their tracks. Calvin Harris recruited 22 buzzy guests for Funk Wav Bounces Vol. 1; their combined powers were not enough to create one Top Ten hit in the U.S. Another producer with a history of pop success, David Guetta, could not crack the Hot 100 with with his Lil Wayne and Nicki Minaj collaboration “Light My Body Up.” And the same goes for Major Lazer, who put out one single with Nicki Minaj and PARTYNEXTDOOR and another with Travis Scott, Camila Cabello, and Quavo, but didn’t get within shouting distance of the Top 40.

The reason that these collaborations no longer connect is that they are founded on the old-fashioned idea that rap and R&B are secondary genres, commercially speaking. When that was true, the featured performer could provide a spark of outsider energy to the pop track and add his or her smaller audience to pop’s big pool of listeners. But rap and R&B are commercially dominant; according to a mid-year report from Nielsen SoundScan, the genres now account for 25.1 percent of all music consumption, while pop accounts for just 13.1 percent. Rappers and R&B singers aren’t outsiders. They’re the ones that keep the industry afloat. Meanwhile, the pop radio audience looks more and more like a niche group composed of listeners who tune in to pop radio precisely because they don’t want to hear much rap and R&B, which they find almost everywhere else: Scan this week’s Pop Airplay chart, and you find just one single that started on hip-hop/R&B radio and then crossed over, Cardi B’s “Bodak Yellow.” As a result, there is no home for many of these pop-star-borrows-rapper collaborations in the current musical landscape.

Intra-genre team-ups are nothing new: “Cross-marketing is an age-old concept,” says Ricky Reed, a writer and producer who has enjoyed hits with Derulo and 21 Pilots. “As far back as Aerosmith and Run-D.M.C. or even before, there was the idea of, we’ll get some of your fans, you get some of our fans.” The barriers to collaboration are now lower than ever: Artists can text files back and forth and record anywhere, and the pop singers who grew up in increasingly genre-less world see nothing strange about reaching across the aisle to a rapper or country singer or electronic producer.

But the landscape for collaborations has shifted markedly in the last few years. “Back in the day, in the 1980s and 1990s, there were bigger sales on the pop side then there were on the urban side and people wanted to cross over,” Ken Johnson, vice-president of urban radio for Cumulus Media (the second-largest owner-operator of radio stations in the U.S. after iHeartMedia), explains. This summer, Nielsen reported that hip-hop and R&B was the most-consumed music in the U.S. for the first time ever, largely because of the two genres’ massive stream counts. “Once upon a time, ‘urban’ to most gatekeepers meant black music,” Anokute says. “It’s safe to say that hip-hop and R&B is no longer urban music — it’s popular music.”

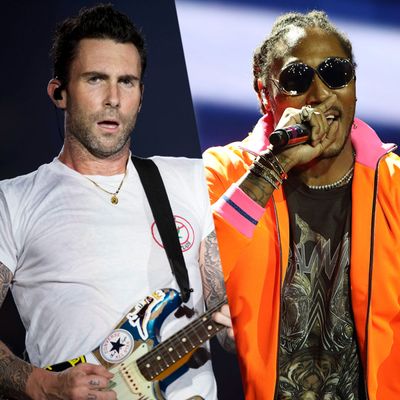

In the new climate, a collaboration may still introduce a listener to an artist he had not heard before: The average Maroon 5 fan, for example, may not have been familiar with Future before the two acts teamed up on “Cold.” But Future doesn’t need Maroon 5 to help him sell records. In fact, the evidence suggests he’s better off without them — Future’s “Mask Off” went to No. 5 on the Hot 100 and is certified quadruple-platinum (4 million units). “Cold” topped out at No. 16 and has not even earned a gold certification (500,000 units).

As these numbers demonstrate, rappers and R&B singers no longer have much to gain from these types of collaborations. And the balance of power has shifted to such an extent that many pop acts appear terrified to put out a single on their own.

As enticing as a hip-hop or R&B feature may seem for a pop singer, it is frequently difficult for these collaborative singles to pick up traction on either radio or streaming services.

Part of this is because pop radio is not hospitable to rappers. Migos’s “Bad and Boujee,” for example, did not crack the Top 30 at pop radio airplay, even though it reached No. 1 on the Hot 100, and massive hits like Future’s “Mask Off” and Lil Uzi Vert’s “XO Tour Llif3” did not register on Billboard’s Pop Songs chart. Tellingly, the only rapper to top the Pop Songs chart this year as a lead artist was Machine Gun Kelly, a white rapper whose single interpolated a 1990s rock hit. As a general rule of thumb right now, if you’re trying to convince pop radio programmers to play your song, the presence of an MC is not an asset.

At the moment, Johnson says, “radio is staying steadfast in, ‘this is an urban station’ and ‘this is a pop station.’” “Urban music is flush with songs and artists; there’s so much product out there they don’t necessarily have to [play collaborations],” he adds. On the pop side of the fence, programmers have frequently united behind records almost totally divorced from hip-hop — songs by Ed Sheeran, Shawn Mendes, Niall Horan, Charlie Puth, Portugal. the Man, and Imagine Dragons have all been the No. 1 records on pop radio.

Ironically, even though streaming has helped create the conditions in which pop stars scramble for rap features, these records have the potential to slip through the cracks at streaming services as well. An official Migos single is almost guaranteed to end up on Spotify’s premier hip-hop playlist, RapCaviar, which has over 8 million followers. But the trio’s collaboration with the latest major label pop act in need of a hit almost certainly won’t. At the moment, there is not a single pop-first collaboration record on RapCaviar.

On the pop playlist side, the allure of the major-label-supported pop act will probably propel his or her latest collaboration single into Spotify’s Today’s Top Hits, which sports more than 18 million followers. Derulo’s new rap collaboration, “Tip Toe,” with French Montana, is on that playlist now. But clearly the streaming numbers, even from a playlist with such a big following, aren’t doing enough to make these records sure things, because the Hot 100 already factors streaming into its accounting, and the singles listed above still haven’t performed well on that chart.

That’s probably because streaming audience on platforms like Spotify and Apple Music tends to skew toward rap and R&B, so the demand for new pop material just isn’t that high. “Look at certain examples of artists like Lorde or even Harry Styles,” Anokute says. “These artists sold millions of records on their previous releases, but on their recent releases, you can’t say the streaming numbers are huge. Look at Portugal. the Man[’s ‘Feel It Still’] — It’s a No. 1 record at Top 40 radio, but it’s not a top-ten streaming record in America.”

Why aren’t listeners finding pop collaboration records compelling? Perhaps because they appear increasingly desperate. “Any time you take a super pop artist and put them with the hottest rapper at the time, that to a lot of people seems reached and forced,” says Jonathan Yip, who has co-written and produced songs by Bruno Mars and Justin Bieber as a member of the Stereotypes. This effect is magnified at a time when hip-hop singles routinely zoom up the Hot 100. “No disrespect to her and her team, but I think Gucci Mane on Selena Gomez’s ‘Fetish’ was far-fetched,” Anokute says. A lot of listeners apparently agreed with that assessment.

A pop artist who relies heavily on features may also struggle to establish an identity that listeners can latch on to — the kind of thing that turns a casual streamer into a monthly listener. Yip thinks this is primarily a concern for young artists. “If it’s too early in somebody’s career, and they get known for just doing collabs, that could be detrimental,” he says.

But too many features can also obscure a more established act. “The pop music mainstream has limited bandwidth for stars, it always has,” Reed says. “If you don’t have a very strong voice that people are connecting with, there’s a good chance you’re not going to be able to sit amongst those stars. If you just load your album with features and dilute your voice, it might be a good short-term play for streams, but long term, I think it can be damaging.”

Then there’s the fish-out-of-water problem: Quality is just one variable out of many in the hit-making equation, but it can be downright difficult for pop singers to make convincing and effective steps into rap and R&B. It doesn’t help that their efforts are often half-hearted; they frequently rely on a pop-world interpretation of Atlanta hip-hop or morose trap soul rather than working with the beat-makers who helped define those sounds. Max Martin produced the Taylor Swift-Future-Ed Sheeran traffic jam “End Game,” and Martin has helped write 22 No. 1 hits, but that doesn’t change the fact that Future sounds better on a Metro Boomin beat.

It’s not only the pop producers who are failing to shine on collaborations. Rappers and R&B singers often have little incentive to turn in their best work on these records because they know they no longer need them. Gucci Mane has rattled off some truly lackluster pop feature verses this year. Future’s contribution to “End Game” sounds as it were designed for a different track.

Even when an artist works with the right personnel to establish a more secure foundation for a collaboration, he may still be out of his element. Since Zayn left One Direction, he has repeatedly declared an interest in R&B, but his collaboration with PARTYNEXTDOOR on “Still Got Time” sank like a stone, despite production from Frank Dukes and Murda Beatz, who have impressive résumés in R&B and hip-hop. Listeners appear to prefer Zayn on clean pop songs like “I Don’t Wanna Live Forever” where his lightweight voice is not required to do much lifting.

Of course, misguided and downright bad collaborations are not a new phenomenon. But if you bought one of these records in, say, 2006, your consumption was logged whether or not you ever listened to the thing. In the streaming world, where 150 streams is the equivalent of a single download, you can test out a record, then skip away and direct your clicks elsewhere. The cost of disengagement has never been lower. Why settle for what Anokute is calling “far-fetched”? All of PARTYNEXTDOOR’s other songs are at your fingertips, as is Zayn’s “I Don’t Wanna Live Forever.”

This is all troubling news for pop singers: There are fewer and fewer reasons for rappers and R&B singers to hop on these records. Sure, it’s an easily obtained major label paycheck — Anokute suggests the cost of most features ranges between $25,000 and $100,000 — and maybe an opportunity to do a favor for label-mates. But Migos’s “Bad and Boujee” did far better in the U.S. than did their collaborations with Katy Perry and Calvin Harris. PARTYNEXTDOOR got more pop radio play with his own track “Not Nice” than he did for his team-up with Major Lazer. Gucci Mane’s “I Get the Bag” was the biggest single of his career as a lead artist, easily eclipsing his collaborations with Gomez or Fifth Harmony.

“Because you put two big acts on a record, that might get your attention,” Johnson says. “But then it becomes, is the record even worth it?” For pop acts still playing by the old rules, the answer to this question seems to be no.