Whether you thought the Strokes’ 2001 debut was the second coming or else asked “Is this it?” when it played, Lizzy Goodman’s oral history Meet Me in the Bathroom tirelessly documented the debauchery and unfulfilled promise of the New York City rock scene in the early 21st century. But as it mythologized Manhattan’s dwindling scene, the book somewhat overlooked Brooklyn, the borough that saw its music culture explode over that same time period, becoming the epicenter for indie music the rest of the decade. Goodman’s most surprising omission was in neglecting to mention the band that would become the most important and unexpectedly popular group of the era, a tight-knit group of friends hailing from Baltimore who played shows in NYC wearing masks, and billed as Avey Tare, Panda Bear, Geologist, and Deakin, before their record label finally suggested a less unwieldy handle for the group: Animal Collective.

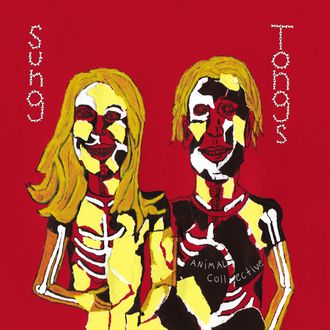

This past weekend, music website Pitchfork celebrated its 21st anniversary with the likes of Moses Sumney, (Sandy) Alex G, and Animal Collective, getting the band to do something they had never done before: play their paradigm-shifting fourth album Sung Tongs from beginning to end. Even if you were a devotee of the group back then, by the time of Sung Tongs’s release in spring of 2004, Animal Collective had already moved on from the material for their live shows. At the time of its release, Pitchfork — founded by Ryan Schreiber from his parent’s home in Minneapolis — was located in Chicago, and the site bestowed an 8.9 rating on the album, breathlessly calling it “a romantic album … in its celebration of innocence and nonsensical shared knowledge … [communicating] a sense of overwhelming happiness at having discovered this strange place.”

Some 13 years on, the album’s charms remain largely intact. Made by its two primary songwriters, Dave “Avey Tare” Portner and Noah “Panda Bear” Lennox, Sung Tongs’ vocal harmonies more closely resemble the album title’s spoonerism of “tongue songs,” yipping and darting around like puppies chasing each other in a yard, their acoustic guitars scrape out cyclical rhythms, and the floor toms conjure tribal dances from Where the Wild Things Are. Listen more closely to Sung Tongs and you can hear the road map that the city’s future luminaries would utilize to chart a new course: Grizzly Bear, Dirty Projectors, MGMT, Vampire Weekend, tUnE-yArDs, Woods, Real Estate, to name a few of the Animal Collective’s offspring (factor Panda Bear’s 2007 album Person Pitch in the equation and their influence spreads even wider). Sure, the Strokes might have copped all the street-tough moves of the Velvet Underground, but in terms of influence, Animal Collective more closely embodied the Brian Eno adage that everybody who bought a Velvet Underground album started a band. When John Cale celebrated the 50th anniversary of The Velvet Underground & Nico at BAM last month, he tapped Animal Collective to participate.

But at the time of Sung Tongs’ release, there was no band less likely to succeed than Animal Collective. As a live band, they meandered from half-formed songs to noise and didn’t always find their way back. Pitchfork called a previous album “pants-crapping juvenilia.” Their first U.S. tour was met with total indifference; “People would throw stuff at us, walk out, give us the finger,” Avey Tare said.

But the magic of Sung Tongs is clear from the opening seconds of “Leaf House.” A song that touches on the grief of the passing of Lennox’s father (three months later he went even deeper on his solo album Young Prayer), the duo wraps it in a dizzying display of churned guitar, woodpecker clacks, and layered ululations that verge on the hallucinatory. The song also shows a break from their previous albums: Spirit They’re Gone Spirit They’ve Vanished, Danse Manatee, and Here Comes the Indian, with the band dialing back the expansive noisescapes for the most part and finally embracing song structures and discernible lyrics.

Previous albums drew on psychedelia as well as the sounds of German progressive rock bands like Can and Amon Düül, which makes sense. In the band’s early days, Portner and Lennox were both clerks at the vital downtown hub Other Music, a shop that specialized in legitimate classics, side by side with more esoteric sounds, including Animal Collective’s early, hand-assembled records. As Ben Ratliff noted in the New York Times, Sung Tongs was “proof that rock bands don’t have to do what rock bands have always done: play the traditional instruments, rehearse, tour and record in the traditional ways.” There was a kaleidoscopic range of music they drew upon: Tyrannosaurus Rex and the Incredible String Band, Sierra Leonean guitarist S.E. Rogie and Music From the Ituri Forest, minimal techno producers like Wolfgang Voigt and Dettinger, and an at-the-time ludicrously obscure British folk singer named Vashti Bunyan (with whom the band would collaborate on Prospect Hummer the next year). It might have read as forced eclecticism, but within a year, Apple would launch the iPod Shuffle, training future musicians and listeners alike to jumble up and knock down barriers between genres as a matter of course.

As became their modus operandi, each subsequent Animal Collective album sounded as alike and unalike as siblings. They experimented along the way as they reached critical and commercial mass with 2009’s exquisite Merriweather Post Pavilion, establishing them as a big festival act and putting them in the pop-culture firmament, from Simpsons episodes to wedding vows, from their own line of vegan shoes to the Grateful Dead allowing the first ever licensed sample for the band’s “What Would I Want? Sky.”

But just as soon as Animal Collective had reached the pinnacle of relevance and sway over an entire generation, they started to pull back. Rather than maintain such status, they continued to test their newfound audience. There was the truly odd and disquieting film ODDSAC, the hyperdense follow-up Centipede Hz and the energy-drink manic Painting With, which didn’t build on the success of MPP so much as scorch the earth around it. Instead of sounding bonkers, there’s now just a song called “Kinda Bonkers.” Try to point to the sort of enchantment the band used to cast on its audience and it’s near impossible to use their cover of “Jimmy Mack” as an example.

But who wants to always be a trendsetter anyway? Animal Collective built their legacy on capturing the playfulness and unease of being children, and then they grew up and had children of their own, which made Saturday night’s show all the more bittersweet. Well after midnight, Portner and Lennox took the stage in beanie and ball cap, 13 years removed from these songs, yet looking as youthful as ever. And with just four acoustic guitars, loop pedal, and a floor tom between them, they re-created the gold thread splendor of Sung Tongs, the sold-out crowd at Knockdown Center calling in unison “Kitties!” and meowing along by the end of the first song, “Leaf House.” And just as the rhetorical question of “Where’s your relaxation?” on their first “hit” “Who Could Win a Rabbit” was echoed in numerous millennials’ dorm rooms back in 2004, now a new generation of college kids shouted along with the duo. They also sang aloud the punch line of “College” and found ecstatic release amid the frenzied thumps and yells of “We Tigers.”

For as many singable moments as the night had, there were just as many wordless, ineffable ones. While the intervening years have elevated Sung Tongs to a touchstone of New York indie music, it remains a deeply weird album. The songs don’t unfold quite like you expect them to, often diverting off course, carried off by their own exuberance. The guitars don’t really get strummed so much as trace fluctuating biorhythms, and the duo lets loose the kind of mouth noises you make when you want to profoundly annoy someone in a public space. Lennox once conjured the giddy sensations of “Kids on Holiday”; now he’s a responsible father tasked with taking his own children on vacation.

Such is the passage of time that lay just beneath that night’s celebration of childhood, teetering on the brink of, yet not quite tipping into, adulthood. The shouts remained cathartic, the swirling vocal effects creating something beatific in the large room. Diaphanous 12-minute Sung Tongs centerpiece “Visiting Friends” retained all of its ability to suspend the sense of time and space, the band providing a portal that allowed its devoted audience to revisit a time that was not necessarily more innocent so much as still idealistic.