On October 25, 2017, Artnet’s Rachel Corbett broke a story recounting accusations of years of sexual harassment and unwanted touching carried on by the well-known publisher of Artforum, Knight Landesman. A singular fixture, impresario, and power broker in the art world for decades known for his red, yellow, and plaid bespoke suits, Landesman was more than just publisher of Artforum. He was the public face of the magazine, forever holding court at openings, after-parties, art fairs, and biennials the world over, sending advertisers notes signed in red pen, signing his name with red pen in gallery books. He wasn’t just a salesman, however. He made connections and helped out young dealers, artists, critics, and curators. He was the person responsible for elaborately arranging the magazine’s ads, placing them to signal status and hierarchies, who was hot and who was not. While I was never invited to any of these affairs, like many, I couldn’t help but notice that he always surrounded himself with young women.

On the same night that Corbett’s story broke, the magazine’s editor Michelle Kuo elegantly announced she was stepping down. Her resignation was widely taken as a protest against the Landesman accusations as well as the business leadership of the magazine, which had protected and even empowered the publisher for so long — up to and including in the immediate aftermath of the Artnet story. (Because of this enabling, numerous art-worlders charge that the other publishers need to be replaced, as well.) But Kuo didn’t say any of this explicitly, only commenting that “I can no longer serve as a public representative of Artforum. We need to make the art world a more equitable, just, and safe place for women at all levels.”

The next day things lurched further, when the magazine announced — quite quickly, all things considered — its new editor-in-chief. The new choice would not be a woman, but David Velasco, 39, who had been with the publication since 2005 and its online editor since 2008. In a way, it was a mark that one part of the publication — the loose, messy, readable, information-packed website, even with its breathless reports of art-world nightlife — was suddenly taking over for another part, long understood as more “important”: namely the forbidding, serious, semi-academic, long-form piety and criticism Landesman had managed to sell as a luxury commodity to gallery advertisers who made the magazine a painfully exclusionary inside-baseball art-world Vogue.

Just hours later, 39 Artforum staffers, including Velasco, publicly condemned “the way the allegations against Knight Landesman have been handled by our publishers,” asserting “we are committed to gender justice and to the eradication of sexual harassment in the art community and beyond.” Velasco then issued his own ardent statement: “The art world is misogynist. Art history is misogynist. Also racist, classist, transphobic, ableist, homophobic. I will not accept this. Intersectional feminism is an ethics near and dear to so many on our staff. Our writers too. This is where we stand. There’s so much to be done. Now, we get to work.” And just like that, an Artforum that needed to disappear was gone.

Amen. And in its place was a new one — morally damaged, wounded, and almost discredited, uncertain that there’s even a future — but with an editor and staff eager to explore this new territory even if it meant getting lost, less obsessed with presenting the magazine as a self-important art-world bible and much more prepared than the magazine had been in a generation, it seemed, to stage loud political fights in its pages.

From the 1980s to the early 2000s, I used to set aside a day to gobble up Artforum to feel part of whatever discourse might be out there or to get mad or scared or spur myself to push my ideas — it felt really like an engine of new ideas then. But after Jack Bankowsky stepped down as editor in 2003 — after bringing the blustery belletristic tone of the writers and the almost-broke Artforum of the 1980s blazing into 1990s, spreading the magazine’s coverage further afield, beefing up its scholarship, initiating annual top-ten lists (and for a time worst tens, before publishers got skittish about offending the geese laying the golden eggs, and it was gone), seasonal previews, and the highly respected Bookforum — the magazine seemed to change. Perhaps a turn to the doctrinaire was in the air as more money was entering the art world, and by the by end of his tenure (the longest in the magazine’s history), Bankowski was being attacked for not being serious enough — which could arguably be taken to mean too gay.

In 2003, under the ultra-self-conscious Columbia-Bard graduate editor Tim Griffin, the magazine shed some of the more lively voices of the 1990s and brought in new people who seemed suspicious of art and enthralled by the Artforum of the 1960s and 1970s, including many of the writers of that era (who returned in force), as well as the theories of the 1980s (including crypto-academics like Slavoj Zizek, Giorgio Agamben, Alain Badiou, Toni Negri and a whole issue devoted to Jacques Rancière). Then, since 2010, under Kuo, a Ph.D. candidate in the history of art and architecture at Harvard, Artforum slowly became a subcontinent of hermeticism.

Artforum was probably never as good as we all thought it was once upon a time, and the art world has been so global for so long now that it’s silly to even think that any one publication could represent the state of affairs. Yet when Corbett’s story broke, Artforum was far more seen than read, not talked about at all in terms of criticism, mocked for its society-nightlife section, considered as a cozy home for Ivy Leaguers, and viewed mainly as a machine that conferred status on select art. Artforum was still “important” in the same way Vogue is, as the holy writ of a particular industry, legible as much through ads as through articles — articles that were hard to read even when you really tried. One well-known curator said, “They took our discourse away from us and became a platform for lectures by unassailable voices that turned out to be clueless.”

Not all was bad; there were great articles and many good writers all this time. Griffin’s magazine played an instrumental role in identifying a now well-known strain of digital neo-appropriation artists like Wade Guyton, Seth Price, and Kelley Walker, and later put Danh Vo on the cover. Kuo’s Artforum excelled at roundtable discussions and thematic issues. Still, these good points and others were invariably drawn into the grim vortex of all the impenetrable hyperacademicism. The magazine — founded in 1962 as a platform for strong voices, real opinion, unique visions, controversial positions, and ideas that hadn’t already been government inspected — had become the sealed-off spaceship Artforum, a faculty-lounge clubhouse publication for an art world that had gotten way too clubby, and way more focused on processing and validating the preapproved than in testing out new ideas. In this way, much good art was drowned out by nepotism, ego, polite acceptance, and propaganda.

Against this parochial purity was the whiplash of actually holding the magazine. Every month this house organ of the high priests was thick with expensive, full-page glossy ads. Sometimes more than 300 pages of them! It was the porn of the art world. Thus, as the magazine’s writers tut-tutted galleries as compromised by the market, the magazine they wrote for was utterly allied with and 100 percent funded by galleries and hypercapitalism. That’s straight-up privileged insularity and boutique radicalism. And annoying.

This disconnect shot into light speed in the online Diary section’s nonstop gossipy accounts of gallery dinners, after-parties, private yachts bound for Hydra and Miami; the comings and goings of a handful of gallivanting super-curators serving on one another’s panels and sometimes even reviewing one another’s shows in the magazine; and sales and lifestyle reports from megadealers. Which makes those pages a strange place from which to stage a revolution for the soul of the magazine.

And yet the website was alive when the magazine had long lost its pulse — energized by young writers who were really out there exploring whatever there was to be explored, and writing about it with an approachable style that made the rest of the writing in the magazine seem purposefully obtuse. When news of a new editor came in October, Artforum was essentially only rehearsing its own history, and more than a few artists commented, “It can’t get worse.”

Which bring us to Velasco. I know him by talking to him in galleries and museums for the last eight years. Most of these meetings have been off the mainline, in smaller spaces, at performances, and the like. He’s a good writer with ecumenical taste, his own eye, interesting, funny, and unafraid to voice negative opinions. This and much more makes me think that Velasco may be the perfect person in the perfect place at the perfect time.

I think this more having just read much of his first issue of the magazine. I was bowled over by a batch of the pieces I read. Suddenly, rather than all of us grousing from the sidelines about what needs to happen at Artforum, it hit me in this January issue that just when we need it most, a new sensibility seems present, something driven, passionate, smart, and righteously indignant but not ironic, arch, coy, and cynical. I actually felt hope. Even inspired.

Velasco’s opening letter, “The Power of Goodbye,” is candid, urgent, and angry. He writes what many of us feel — of “having all the wrong education and just some hot faith in art.” That fits the deeper art-world profile of misfits and seekers in search of communities, new families, like minds, air to breathe at a moment when the old magazine seemed to suggest that all new possibilities were already foreclosed or channeled through a very narrow conceptual-aesthetic lens. The job of art criticism at the magazine had become merely to survey the canonization being done by museums and megagalleries so big and predictable that they might as well been museums. Many of these writers then wrote catalogues or curated shows for these very spaces. It was monolithic and enervating. I didn’t know how alienated I felt around that world — how distant it was from the worlds that all the people I know inhabit — until I read Velasco’s letter, which put the problem so neatly into words.

Addressing not just Artforum or the art world but wider rotting power structures of “asthmatic masculinity … fueled by the drives of angry, sad or self-loathing men who are scared,” Velasco rhetorically wonders “When will it just die?” Next you read him shifting from the power of the editor-in-chief to a person sharing power as he writes about being around a “brilliant staff” — most of whom are female (Griffin and Kuo need commending here) — “who I believe in, who inspire in their intelligence and bravery and desire to do right by others and to find new ways to be and to organize power.” When was the last time we read the words “a desire to do right by others” in Artforum? Imagine working at Artforum with an editor that had just written this! It’s thrilling to think of this magazine as expressing a collective spirit, contradictory opinions (or opinions at all), vision, pith, irreverence, and passion. The last vestiges of the avant-garde are when people put themselves out there in ways that are radically vulnerable, raw, open to failure. Recognizing that change takes time and doesn’t come easy, Velasco writes, “We’re still figuring things out at Artforum as one sad man I once knew goes off and faces a fate of his own making.” That’s raw.

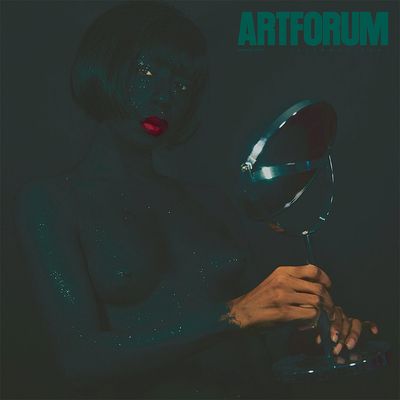

The January issue has smart, accessible articles written and illustrated by artists, many of them turning topically to real-world subjects rather than insular or technical matters that might’ve preoccupied the magazine in earlier eras. Nan Goldin writes about her experiences with the opioid crisis, Kia LaBeija on being born HIV-positive (her topless cover self-portrait is about total risk and owning of self), and Donald Moffett’s what-might-have-been moment imaging Hillary Clinton’s presidential photographs makes you stop in your tracks with sadness. Critic Johanna Fateman writes on power, sexual violence, “the unremitting sexism and reverberating trauma of Trump’s America,” and being “recommitted to feminist first principles.” Reliable hand Molly Nesbit really rises to the occasion, remembering the late art historian Linda Nochlin as “a swan.” Richard Deming writes of John Ashbery’s luminous way “in which art … imparts a deep pleasure.” This is the first appearance of the word “pleasure” in this usage in at least a decade. The ice has been broken.

Finally, curator and transgender activist, Paul P. Preciado’s “Baroque Technopatriarchy” should become required reading for those seeking ways through this paradigm shift. Preciado identifies “archaic necropatriarchy” (the male monopoly on violence and the ability to give death), “heterosexual-colonialization” (patriarchal sovereignty and heteronormativity used to define what it means to be human), and “the pharmacopornographic regime” (the manipulation of genomes … to alter the body’s appearance and the invention of novel conceptions of gender, intersexuality, and transsexuality) as being behind the current fight for the control and territorialization of our bodies, our politics, and our environment. Preciado sees “the Trump era as a recrudescence of necropatriarchal technologies of power and the implementation of the colonial notions of race and sex within a sophisticated pharmacopornographic framework.” It’s a mouthful but Preciado’s universe, as well as much of this issue, starts to add up to necessary clarities, metaphysical handles, and difficult visages that spur feelings of rebellion and revolt.

All of these writers are unafraid to name the disease. In this way, they give hope by taking us out of our private isolations and political solitudes. Each is a pleasure to read, returning bodily confirmation to Artforum. They remind us that change can happen with only one person or a handful of people acting up. Change happens when strong voices are allowed to mature in public, when people take stands without preset or puritanical agendas, aren’t afraid of giving up hierarchies, being wrong, and are honest and earnest. Having a “hot faith in art” has always gotten us through times like these. I haven’t felt this way about this magazine in a long long time. As of today Artforum is no longer a lost cause or a dream anymore. It may be the real thing.