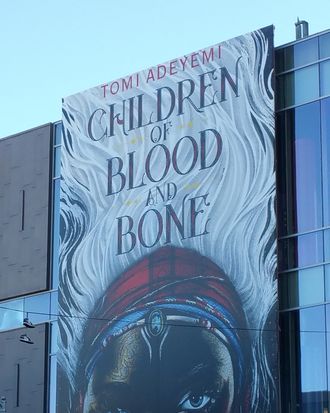

This week, a mysterious figure appeared on a 42-foot high billboard on the side of the Madame Tussauds wax museum, down the street from the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Only the top part of her face was visible — fierce gray eyes, dark-brown skin, bone-white hair rising into the air like smoke. She seemed to be levitating above Hollywood Boulevard, above the chain stores and the traffic and the celebrity footprints, as though she possessed some magical power, which she does. Unless you’re a devoted fan of young-adult literature, you will not have heard of Zélie Adebola, but soon, she will summit the peaks of popular culture like Hermione Granger and Katniss Everdeen before her. Zélie is not the first black heroine of a young-adult fantasy series, but she is on track to become by far the most famous.

The book, Children of Blood and Bone, due to come out March 6, has been called “a brutal, beautiful tale of revolution, faith, and star-crossed love” (Publisher’s Weekly), and “a timely study on race, colorism, and power and injustice” (Kirkus). To conjure the fantastical realm in which it is set, a land of spirits and giant snow leopards, its Nigerian-American author, Tomi Adeyemi, drew on West African mythology, which she researched during a recent fellowship in Brazil. She wrote the first draft in one feverish month. Less than a year later, at the age of 23, she sold the manuscript in a seven-figure deal rumored to be among the biggest in YA history. (“We paid a spectacular advance for a spectacular novel unlike anything we’ve read,” Tiffany Liao, her editor at Henry Holt Books for Young Readers, told me in an email.) A film deal quickly followed, and since then, Children of Blood and Bone has appeared on dozens of lists of the most-anticipated books of 2018. At New York Comic Con last summer, fans waited in lines for hours for a chance to meet Adeyemi, though none had yet read the book. Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education, who focuses on race in children’s and young-adult literature, understood the impulse. “A book like this would have been beyond my imagination as a kid,” said Thomas, who is 40. She sees the publishing industry’s rapturous embrace of Children of Blood and Bone as the result of decades of activism aimed at making the industry more diverse. “What I love most about the idea of Children of Blood and Bone is that it moves black protagonists to the center of the fantastic — we are no longer in the margins of the mainstream imagination. Many black YA writers my age have lumps in their throats because when we were 24, those doors were glued shut.”

The book takes place in a country called Orïsha 11 years after magic has vanished from the land. The King has slaughtered all the Magi — magicians who could draw on the power of gods and goddesses to summon fire, darkness, spirits of the dead. Zélie sets out on quest to restore magic, and to defeat the king, who has murdered her own mother. This week, I caught up with Adeyemi to talk about the inspiration for her work, why she’s bored by Lord of the Rings, and what a book like Children of Blood and Bone would have meant to her as a kid. Plus, check out the book trailer below, released exclusively to Vulture.

I’ve read that your first attempt at writing a novel was inspired by seeing the backlash that the Hunger Games movie got from some viewers who were apparently upset to discover that Rue was black. How did that motivate you to start writing?

It’s actually hilarious, because it seems like we’ve come completely full circle. Now, everybody is losing their minds over Black Panther and its opening weekend totally eclipsed the Hunger Games, and A Wrinkle of Time is coming out next month, and it all feels really good. But in that moment it was really — I know this might sound dramatic, but there’s no other word — it was actually just soul-crushing. Especially during that time in my life.

What was going on in your life then?

It was my freshman year at Harvard. I grew up in a predominantly white community, Hinsdale, Illinois, and given that, I feel blessed because I could still count my experiences with blatant racism on two hands. I thought racism was the substitute teacher picking on you because she assumes that you’re a delinquent and she doesn’t know you have the highest score in the class. But then I got to college, and that’s when the shooting of Trayvon Martin happened, and that was terrifying. I knew racism could emotionally hurt, but up until then, I thought we were past the time when racism could actually kill me. And then we went through the trial, and I saw oh, also, it’s not only that you can be killed, it’s that your killer is going to walk free.

So college was this big awakening. Then came The Hunger Games — those stories were supposed to be my safe spot. Those characters were just supposed to be characters. I thought it wasn’t really about the color of their skin. But then I found out that people were bringing their real-world hatred into that fictional world. They said, “Oh, yeah, it’s not sad when a 10-year-old girl gets speared to death because she’s black.” And they’re saying it in public, too, on the internet. They were so bold and so unashamed. It was both terrifying and heart breaking. If they don’t feel anything seeing a fictional black girl die, then our world is in a much worse spot than I thought. I am a lot less safe than I thought.

But after the terror comes the, “Oh I’m going to get you.” [Laughs.] At least for me. I’m going to get you, because I’m going to make something as good as The Hunger Games, and everyone is going to be black, and you’re going to have to enjoy this thing with all black people and that’s going to suck for you! That’s how I go through things. Something hurts me, I feel that hurt deeply, I shed my tears, and then it’s like, okay, but now I’m going to get you. Not necessarily this month, not necessarily this year, but give it time. I will clap back. And you will eat your words.

It’s amazing what a difference six years can make, especially in a genre like fantasy, which has been dominated for so long by white people.

We’ve been told the same story for so long. We’ve seen literally 1,000 Lord of the Rings movies. I keep thinking about what it would have been like if I had seen this growing up — if I’d seen someone even darker than me, someone who doesn’t have straight fantasy hair, but a curly magical afro. I know what it would have done that for me, because I know what it did for me when I did see these things for the first time. Like with Kerry Washington on Scandal. I remember being like — that’s me, I’m the main character! I’m badass! I’m emotionally complex! I’m making out with the president! Cool cool cool! You don’t realize what’s missing until you see it. And then once you do, you’re like, why do I feel like I could lift a car right now? So this is why white men feel so great all the time.

This is the explanation.

Yeah, because they’re always seeing themselves doing amazing things. Right now, I feel like we’re in this black-girl-magic renaissance. Last week, Dhonielle Clayton’s book The Belles came out, and in April, Justina Ireland’s Dread Nation is coming out, and seeing our three books next to each other — I’ve never seen books like this in my entire life. It’s actually incredible.

I’m this excited as an adult consumer, so I can’t even imagine what this specific year is going to do for so many children, especially so many black girls. They are being flooded with, you are amazing, you are beautiful, you are powerful, you can kill zombies, you can do magic, your hair looks amazing. Even though the world is a very scary place, if I just look at that part, I feel like: okay, I could have a daughter right now. She’s not going to have to go through this period of hating her hair and hating her skin. Not to say that these books are going to completely eradicate that, but it’s going to make a huge difference, because you hate yourself when you think you’re different, when you think no one is like you.

How old were you when you wrote your first story?

My very first story, I was around 5, and I really just wrote myself. When I was 5, I loved myself so much I gave myself a twin named Tomi. Everything started out fine. But then I didn’t write another black character until I was 18. I look at that gap, and just the thought of me sitting alone in my room reinforcing the lies the world told us pisses me off.

What kind of characters were you writing in those years?

The protagonists were either white or biracial, because I thought those were the only people who were allowed to be in stories. It wasn’t a conscious decision, which to me is why it’s scarier. Somewhere in there, I’d internalized this idea. I’m writing stories alone in my room, and I don’t write black characters because I don’t think that’s allowed. And my senior year, I finally realized how messed up that was. So even before the Hunger Games, I realized I needed to write black characters with really big hair. That was one way I could start teaching myself to love and accept myself and not wish I looked different, or that my skin was lighter, or that my eyes were hazel. It was so easy for me to describe those features in the books I was writing as desirable, but it wasn’t easy to write “she had really dark skin” — I didn’t have the language for it. So that was the start of my journey.

I spent 12 years of my life writing stories without black people. That’s insane to me. It’s insane that I could have believed in magical portals and dragons and all that stuff, but to believe a black person could be experiencing those things was unimaginable.

So when you started working on Children of Blood and Bone, were you drawing any inspiration from the classics of the fantasy genre — the 1,000 different versions of Lord of the Rings, as you say?

Here’s where I’m going to be crucified: I haven’t actually read Lord of the Rings. I haven’t watched Game of Thrones. [Whispering.] I’m whispering because I know they’re going to be like “burn her!” I’m not saying they’re not great, it just wasn’t doing it for me. So I couldn’t be influenced by LOTR because I literally couldn’t get through it. There are just all these short men running around.

I’m more influenced by anime. That was my first love. When I think about my childhood, it’s Harry Potter, but really it was Naruto, it was Bleach, it was Death Note. Those are epic, vicious tales. Right now my inspiration is Attack on Titan. I know I need to make something as effed up and as incredible and as bleak as Attack on Titan. Right now on my bookshelf, I have my only hardcover finished copy of Children of Blood and Bone, and then to the left of it, I have Shadowshaper by Daniel José Older and to the right of it, there’s An Ember in the Ashes by Sabaa Tahir, and above it is Avatar: The Last Airbender — Children of Blood and Bone is the baby of those three.

The idea that magic is a thing that has gone away and needs to be recovered is a common theme in fantasy books and older fairy tales, too. I’m curious why that theme resonated for you. In the real world, what’s the thing that you think has been lost that needs to be recovered?

For me, this theme hits home. I think everyone from a marginalized background can relate. You’re young, and the world is full of color and hopes and dreams. And then one day you have an experience that teaches you the world isn’t what you thought it was.

It teaches you that because of the color of your skin, people will treat you differently. Strangers will hate you. People in power will use their power to further disenfranchise you. People you pay to protect you will use their weapons to systematically hunt you down and kill you.

Living through that, it’s like watching a world full of color fade to hues of gray. To me, there’s no more powerful metaphor for that than watching a world that used to be full of magic get that magic violently ripped away.

People are talking about this as one of the biggest books of the year, and on top of that, the book carries this political weight — one of the first YA epic fantasies written by a black woman, featuring a black woman of color. Let’s talk about how you’re handling these expectations.

At this specific moment in time, I don’t feel the pressure of that because the book is done. For the eight months we spent intensely revising the book, absolutely. I knew the importance of this book and its potential impact on readers from all backgrounds, which meant every single word, every plot point, every character action, every element of the world — literally everything — has been through the ringer.

Up until a few days before we had to turn in the final text, we were still editing, still discussing, still analyzing. I put an insane amount of pressure on myself to get this book right. I know that no matter how hard you work you won’t be able to stop people from coming at something or trying to pick it apart, but I don’t have to feel pressure or worry now because I know that I did everything humanly possible (and then some) to put out the best book possible.

I think for me the biggest challenge is to maintain sanity and maintain time for everything. I really destroyed myself for this book.

Tell me more.

It was mostly all nighters. So many all nighters. Usually when a book is getting published, they make the book deal and then the book will be published a year and a half to two years later. We tried to do this in 11 months. Also the book that Macmillan bought was 400 pages, the advanced copy is 600 pages, it would be one thing if we just added 200 pages, because that’s not actually that bad. But we freaking ripped up the pipes. The book is so much better for it, but it was grueling.

I want to hear about the your research into the African mythology that inspired the magic in Children of Blood and Bone.

So I was in Brazil to research something completely different: how their history of slavery compared to ours and how the formation of an Afro-Brazilian identity compared to African-American identity. But the museum that had been my focal point — the whole reason I was able to justify going to Brazil — was closed for renovation. So when I realized this, it was raining, and I wandered into a gift shop to stop my hair from getting wet, and the gift-shop owner was kicking people out who were clearly there to not get wet. So I was like, “I’ve gotta look interested!” I started looking around and I picked up this poster of nine different Orisha. I had no idea what it was. I’d never seen anything like it. This ties back to what we were talking about earlier — You don’t realize that you’ve been surrounded by white Jesus and Zeus until you see black gods and goddesses and you’re like, “Holy wow!” I knew instantly I was going to do something with it, I just didn’t know what the story was yet. I was way more moved by just seeing that gift-shop photo than by any of the other slave-trade research I was doing. So I pivoted. And I started looking into the deep history of stories about these gods and goddesses — I call them that, because they’re similar to saints or angels. And a few months later, I started to think about what it would be like to do a story with a world based off those gods. I knew then that I had something worth writing that we hadn’t seen before.

Are there any updates on the movie that you can share? What’s that process been like? How involved are you?

The process has been wonderful! Everyone working on this movie is so passionate and excited about this project, and I couldn’t have asked for a better team to be behind Children of Blood and Bone. At this moment in time, I’ve had a few conversations with the screenwriter [whose identity is still a closely guarded secret], and it’s been incredible collaborating with him. I’ve also met with the team at Fox 2000 and Temple Hill Productions, and we’re continuing to meet as we get closer to putting all the people and pieces in place to start production. I can’t give any concrete dates away, but I will say that having watched Black Panther twice in two days, I am so excited for Children of Blood and Bone to make its way onto the screen!

This interview has been edited and condensed.