In 1971, Don McGregor was a proofreader at Marvel Comics, and one particular thing was driving him nuts. There was a series with the cringe-inducing name of Jungle Action, and its contents were primarily reprints of 1950s tales about white people — Jann of the Jungle, Lorna the Jungle Queen, Tharn the Magnificent — having adventures in ill-defined African locales. “I kept saying to them, ‘I can’t believe you guys are printing this racist material in the 1970s,’” the 72-year-old McGregor says in his stout Rhode Island brogue. “Finally, it was decided to put some new material in, and I said something like, ‘It needs to have a black jungle character. Something.’”

Marvel really only had one such property at the time. His name was T’Challa and he was the superpowered monarch of hidden Wakanda, an African nation made technologically advanced thanks to the presence of a rare metal called vibranium. He was best known by his nom de guerre: Black Panther. T’Challa had been created in 1966 by Jack Kirby and Stan Lee, but honestly, he hadn’t done a whole lot of note since then. He’d pop up occasionally to pal around with the Fantastic Four or the Avengers, but that was about it. So second-rate was the Panther that when McGregor made his plea, he didn’t have the guy in mind.

“I wasn’t even thinking of the Black Panther at the time, and certainly not that I was gonna get a chance to do it,” McGregor swears. Imagine his surprise, then, when he, a 20-something with virtually no comics-writing experience, was asked to put his money where his mouth was and write new Panther stories for Jungle Action, starting in 1972. “I read every book he’d been in, and I started making notes about what I thought really worked and what needed to be looked at, because we really didn’t know how it worked.”

Nearly 50 years later, it’s safe to say that people have figured out how Black Panther works. T’Challa just made his big-screen debut in an eponymous Marvel Studios film directed and co-written by Ryan Coogler. The response to it has been astounding — it’s been regarded as a major cultural moment for months, if not years. It broke ticket presale records. It spawned massively popular hashtags. Reviews have been overwhelmingly positive. The character and his film are already cultural icons. And it’s entirely possible that none of it would have happened without McGregor.

In the pages of Jungle Action, he and a trio of pencilers — Rich Buckler, Billy Graham, and Gil Kane — dreamed up Black Panther’s first solo saga. It was an operatic two-year tale of death, love, and revolution with the sizzling title “Panther’s Rage.” In it, the character came into full flower for the first time, and it gave birth to T’Challa’s greatest foe: a rival to the Wakandan throne named Erik Killmonger. One can debate McGregor’s influence on the Black Panther movie versus that of other Panther writers like Christopher Priest, Reginald Hudlin, and Ta-Nehisi Coates. But it’s undeniable that the picture wouldn’t have its much-praised, Michael B. Jordan–played bad guy if not for McGregor and the late Buckler.

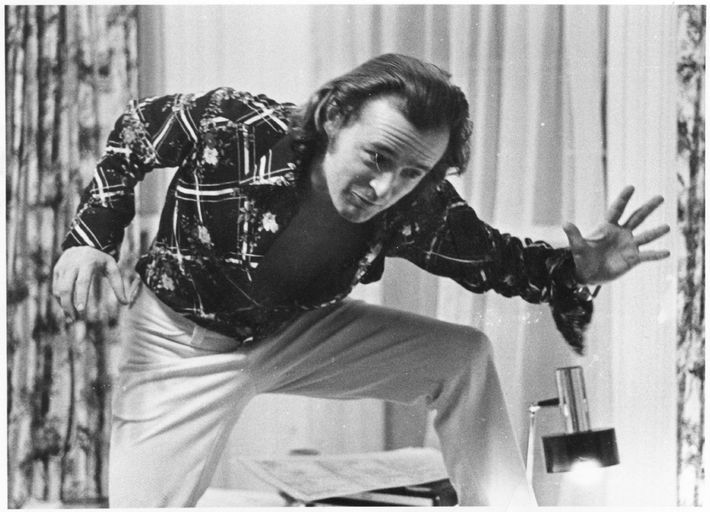

The two men were unknown quantities at Marvel. McGregor, born in Providence, had held a wild array of jobs over the course of his young adulthood: security guard, bank and movie theater employee, even an MP in the National Guard during the riot-prone late 1960s. In that latter gig, McGregor saw raw bigotry firsthand and was repulsed. “You have to be careful about reporting racists in a Military Police Unit, ignorant bastards who talk big-mouthed, small, bitter-minded, violent racist thoughts of what they would do to blacks if the unit were called into action,” he would later write. Combating racism would go on to be a central passion for him. A fan of pulp storytelling, he got his first comics-writing gig in 1971 (a horror story for Warren Publishing) and right around then landed the Marvel proofreading job. Buckler — a Detroiter by birth — had been in the industry a few years longer, but had done little of note and had only started working for Marvel in early 1972.

So when the higher-ups paired them up to do Panther stories in Jungle Action, no one — including them — could have predicted what they’d come up with. They had considerable editorial freedom due to the fact that no one was really reading the series at the time. The two men quickly became close. “We worked side by side — I mean, literally,” McGregor recalls. “Rich actually found me a place to live in the Bronx so that we could be close by each other. So I literally would go to Rich’s apartment after work from 8 p.m. to 10 p.m., and we’d sit and I would do Panther poses for him, or we would discuss design.”

It was in that Bronx apartment that Killmonger was born. McGregor wanted to situate the Jungle Action stories in Wakanda, which T’Challa had recently departed to go on American adventures. That meant an all-black cast — something never before seen in mainstream comics. And an all-black cast meant another rarity: a black bad guy. “I did not want any more white people stumbling into Wakanda to go steal the vibranium. I mean, how many times can you do that?” McGregor says. “So my first thought when looking at it was, Well, he’s been away from Wakanda and is coming back, and what makes sense? Politically, things could be happening. I started working on the idea of a revolution within Wakanda because he’s been away for so long.”

Every revolution needs someone at the vanguard, so McGregor and Buckler set out to decide who that would be. The former contributed a startling name. “By that time in comics, so many names had been used for villains and heroes,” McGregor says. “I think every noun, just about. I wanted a name that was striking and that would kind of reflect their personality, give you some indication of a strong visual trait about them.” Suddenly, a moniker appeared in his brain: Erik Killmonger. He has no idea where it came from. “I don’t think I struggled a long time with the name,” he says with a laugh.

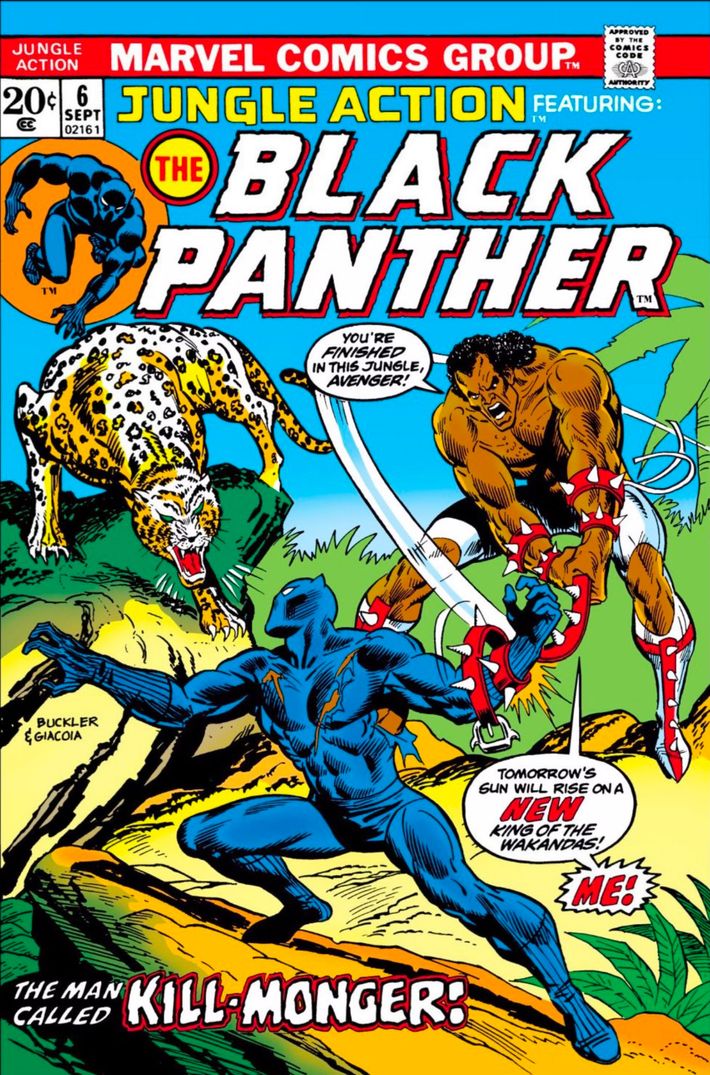

Buckler, sitting at McGregor’s side, concocted an equally startling look for this nascent rival. He would be a bare-chested, towering mountain of a man, clad in white tights and red-and-white spiked wrist straps and boots, bearing a massive spiked whip, and adorned with a curly mullet. McGregor says he and Buckler wanted to subtly convey a racial and historical component with the straps and the whip. As he puts it, “I liked the idea of the spikes, and it really just gave not just a sense of power, but a sense of the legacy of violence from slavery.”

No sooner had they’d created Killmonger than they decided to make him a central figure on the cover of their first chapter in Jungle Action No. 6. McGregor lauds Marvel for allowing him to present such a richly fleshed-out black cast, but recalls pushback on the covers front. “We had him on the first cover, and then I was told that he could not appear on the covers,” he says. “I’m not sure they were that comfortable with having a black villain of that strength and ferocity that Killmonger had, going against the Panther.”

But whatever editorial tentativeness there may have been, it didn’t show in the pages of “Panther’s Rage,” which presented a tale about black Africans unlike any other that comics had seen. Indeed, it was a story unlike any before seen in that medium. Although it was serialized throughout 13 issues, it has sometimes been called the first graphic novel, due to the fact that it was an uninterrupted, cohesive comics narrative stretched over an unprecedented length. In it, T’Challa returned to Wakanda with his African-American love interest, musician Monica Lynne, only to find that something was deeply wrong in his kingdom.

In the opening scene, T’Challa leaps through the air to save an elderly Wakandan being held captive by two other Wakandans. The first two lines of dialogue, spoken by one of the captors, immediately establish that someone sinister has appeared in the country: “Come, wizened one, spare yourself pain! You’ll answer Killmonger’s questions!” The Panther defeats them easily, but is confused about what’s happening. Back at his palace, he asks his closest adviser, W’Kabi, what’s up. “What tears at us is a whispered threat — that leaves terror in his wake!” W’Kabi replies. “Erik Killmonger! Perhaps if you’d spent more time here, you would not have had to ask!”

T’Challa, appropriately guilted, ventures to a village destroyed by Killmonger and the villain suddenly appears and attacks him. They tussle and Killmonger gets the upper hand. “You could not have hoped to win!” he cries as his pet wildcat, Preyy, pins T’Challa down. “Wakanda became a toy to you — a bright shining gem — and on the day that happened, you lost your kingdom!” He tosses the Panther over a waterfall and assumes him dead. It was an alarmingly intense first issue, showing our hero at the receiving end of physical and moral defeat.

Over the course of the subsequent installments, a pattern emerged. T’Challa would attempt to track down Killmonger (who we learned was born as N’Jadaka of Wakanda, but spent time in the U.S., where he adopted his alternate name). Along the way, the Panther would battle one new villain after another. McGregor had a talent for off-kilter names and granted them to these baddies: King Cadaver, Baron Macabre, Lord Karnaj, and — perhaps most delightfully nutty of them all — Salamander K’Ruel. One by one, the Panther would beat them, but his long, exhausting journey wore on him. Meanwhile, we’d get interludes in which the eternally grinning Killmonger would march his way toward the palace, expecting to easily take over the country with his violent mandate.

The tale was an aesthetic feast. Buckler left after the first three issues, but was replaced by the immensely talented Billy Graham, one of the only black creators in the industry. Legendary penciler Gil Kane would pop in and out, as well, but Graham was the real star. His intricate layouts and graceful action were unlike anything in comics at the time, and they synced well with McGregor’s famously elaborate prose.

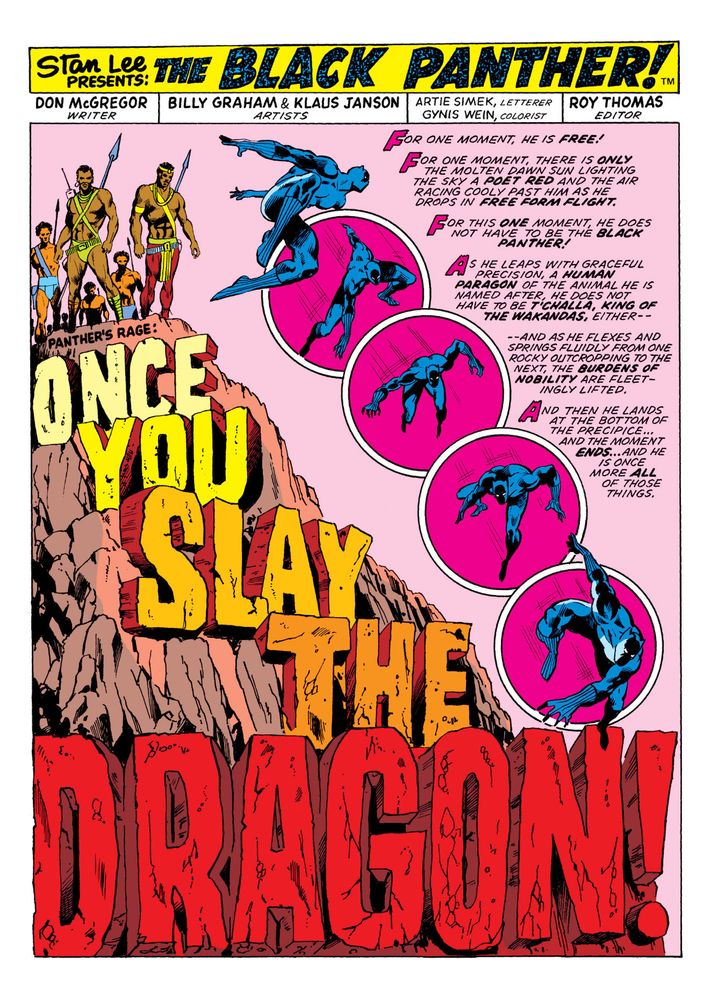

Take, for example, the title page of Jungle Action No. 11. Ostensibly, all that’s happening is T’Challa leaping down from a rocky hilltop. There isn’t even any dialogue. But Graham fills half the page with the title of the story — “ONCE YOU SLAY THE DRAGON!” — in the form of massive carved stones along the hill’s side. He depicts the Panther’s descent by constructing four circular panels within the main panel, each circle containing a new pose during the leap. Inker Klaus Janson provides vivid textures and colorist Glynis Wein offers up rosy-fingered dawn. For his part, McGregor writes a kind of lush, dense narration that, still to this day, is rarely found in superhero comics:

For one moment, he is free! For one moment, there is only the molten dawn sun lighting the sky a poet red and the air racing cooly past him as he drops in free form flight. For this one moment, he does not have to be the Black Panther! As he leaps with graceful precision, a human paragon of the animal he is named after, he does not have to be T’Challa, king of the Wakandas, either — and as he flexes and springs fluidly from one rocky outcropping to the next, the burdens of nobility are fleetingly lifted. And then he lands at the bottom of the precipice … and the moment ends … and he is once more all of those things.

This approach powered the lengthy narrative and its explorations of everything from the complexities of the romantic relationship between T’Challa and Monica to the responsibilities of a leader. When T’Challa finally gets his rematch with Killmonger, he muses that his path to this moment had been a challenge not just due to the physical battles, but because he was plagued by “all the guilts I left unvoiced!” Nevertheless, he concludes that, “while I have yet to conquer them — I am no longer their slave!” This idea of T’Challa facing a serious crisis of confidence in the face of an uprising is a key component of the film, and owes a notable debt to McGregor and his dialogue. Panther ultimately tosses Killmonger over a waterfall and leaves him for dead, but it is a Pyrrhic victory. The subsequent narration notes that “the only survivors … are victims themselves!”

“Panther’s Rage” was an artistic high-water mark for early-’70s superhero fiction, but it didn’t sell particularly well at the time. Nor was it regularly reprinted in the decades that followed. However, many who did get their hands on it over the years were awed by it. “This overlooked and underrated classic is arguably the most tightly written multi-part superhero epic ever,” wrote the late comics and animation writer Dwayne McDuffie. “It’s damn-near flawless, every issue, every scene, a functional, necessary part of the whole.” “‘Panther’s Rage’ was the first great Black Panther story, combining a thrilling saga with a series of great stand-alone tales,” declared comics journalist Tom Speelman.

As such, McGregor has come to be known as one of the small handful of people who fundamentally shaped this month’s biggest movie star. He would go on to write a few more Panther stories after “Panther’s Rage,” including one where T’Challa fights the Ku Klux Klan and another where he grapples with South African apartheid (the latter of those two introduced another film character, Angela Bassett’s mother figure Ramonda). He stopped writing comics regularly in the late 1990s, but is returning to T’Challa for a short story called “Panther’s Heart” in this month’s Black Panther Annual No. 1.

Even though his comics career is mostly over at this point, McGregor still gets to revel in the fruits of his labor. “Panther’s Rage” is back in print, and he attended the premiere of Black Panther a few weeks ago. Though he didn’t meet Jordan, he did chat with T’Challa actor Chadwick Boseman and was impressed by both men’s performances. “Michael collected a dynamism and an emotional quality that Killmonger should have,” he says. “T’Challa’s the guy who, when he steps into the room, he really doesn’t have to raise his voice. You just can sense from him the inner strength that he has, and the clear-cut sense of purpose that he has, but also the physical strength as well. I think Chadwick captured all of that.”

And as for his own legacy? McGregor seems happy to be recognized, but is quick to point out that he was never thinking about any of that when “Panther’s Rage” began and the seeds were planted for a megablockbuster. “When I was writing books,” he says, “the only thing I was thinking about was, What’s the next page?”