On Abraham Lincoln’s 209th birthday, four American firsts have brought destiny, dignity, respect, and art together to remind us that this country embodies love, hope, and things bigger than the misrule and chaos that have come out from under rocks and have seemed to define who we are and who we will be. Today at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C., four shots of love: the first official portrait of an African-American president, painted by an African-American artist, and the first portrait of an African-American First Lady, painted by an African-American woman artist.

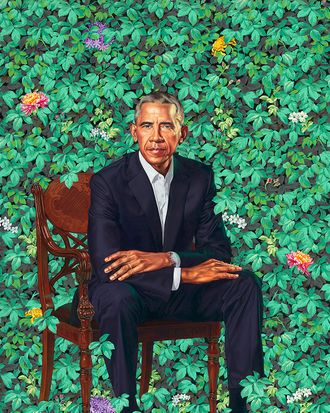

The president’s portrait is by Kehinde Wiley, 40, a mega–art star whose work commands astronomical prices, known for sartorial snazz, runner of a major studio with assistants working on canvases, maker of highly precise, plastic-looking photo-realistic images of black men and women placed in fabulous surroundings, pictured in the guises of mythic figures, ancient gods, and historical hotshots like Napoleon. Explaining his choice of Wiley, the former president said, “What I was always struck by when I saw his portraits was the degree to which they challenged our ideas of power and privilege.”

Happily, Wiley rises to the occasion, giving us a troubled, human, pure-of-heart Rock of Gibraltar seated on a hard wooden seat that hints at the bare-bones look of African tribal chairs. The president is seated in and among — not out front and center of — a verdigris overgrowth of flowers. He’s almost fighting for the stage that is already growing over him. But he remains. Real, insistent, a reminder or compass. By not resorting to his usual bravado and monumental, heroic grandiosity that tends to so elevate his subjects that the paintings become closer to kitsch, Wiley’s treatment of Obama allows the person and the ideas represented to bloom much more fully.

Seating the president lower this way, enmeshing him in an overabundant, highly colorful natural setting, sustains a much more mysteriously human presence, brooding, reconciling, not merely knowing, separate, but kindled with fiery curiosity, a simple inner elevation that brings us to the border of the ordinary and the extraordinary. It’s exactly the metaphysical place Obama embodied as president of all America. The pose and enclosing him this way will irk many who will see Obama being made too normal, small, not central, not in grandeur, not an imperial god. I think the picture is true to the way Obama carries himself. He’s clearly the central subject but not entirely central; there’s a lot going on around him to contend with, negotiate; he’s open to his surroundings, part of them, bigger than they are but not the only thing present. He’s still fighting for space. Wiley even gets some of Obama’s melancholy, his tranquilizing thoughtfulness, the whispering sense that he will not be smote.

True to Wiley’s style, the portrait is at once photo-realistic and madly decorative. Almost too much to take in. Perhaps knowing the identity of the sitter lifts this painting from the usual woodenness that often quickly overtakes Wiley’s pictures and that too quickly gives the game away, sending only one message of a black person being given pictorial dignity. It feels good; it is good; but many of his paintings tend not to last as much more than conceptual-art posters.

Not so the Obama painting. A world emerges as well as a worldview. Wiley depicts African blue lilies, jasmine, and chrysanthemums to represent and map Obama’s journey from Kenyan roots, to Hawaii, to the official flower of Chicago. Like the president, Wiley also had an absent African father and an American mother. Another American story. This empathy is here, the bottom-up roots, lifting one’s self up, being lucky, challenging conventions of what things look like, bringing those things to the centers of American life. In the first case a black president; in the other, black faces in our museums after several millennia of willfully turning a blind eye.

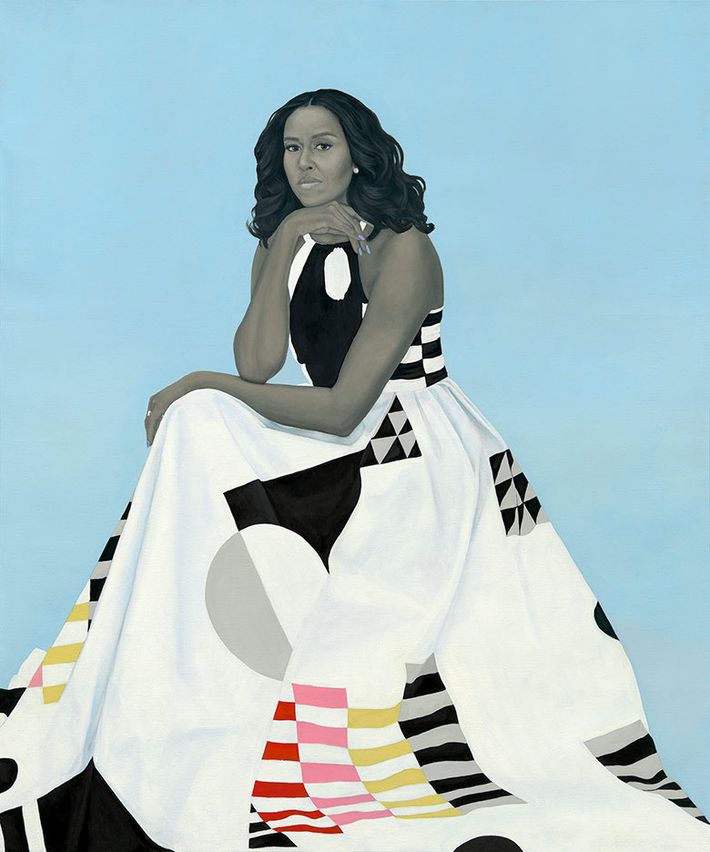

Then there’s the portrait of Michelle Obama by Amy Sherald, 44, who lives in Baltimore. Sherald had a heart transplant in her 30s, and her work only just came to light under the tutelage of an earlier portrait exhibition overseen by National Portrait Gallery curator, Dorothy Moss. At the unveiling, the president — who also thanked the Studio Museum’s Thelma Golden for helping to make these commissions possible (thank you, Thelma, too, for always ringing these bells) — he rightly noted that Sherald’s portrait of the First Lady captures “the grace and beauty and intelligence and charm and hotness of the woman that I love.” He then thanked her mother for — “in addition to providing the hotness genes” — being “such an extraordinary rock and foundation stone for our family.” Indeed, Sherald portrays this woman whose great-great grandfather and great-great-great grandmother were slaves in ways that challenge every convention. Seated, wearing a chic black-and-white Michelle Smith–designed gown, her hair down and wavy, her bare arms blazing, chin resting on her hand, her other hand draped across her lap, she is a visage of the invisible elements of intrinsic inner and outer stature. An everyday queen of heaven.

She is grand, elegant, gorgeous, but her jackrabbit-quick wit is right there. Set against a monochrome flat powder-blue, the First Lady is a guide star to another kind of glamour, a serious spirit whose sorrows were released, who spread warmth, respect, a sly sense of humor, and protectiveness. And a different idea of female power and beauty: As she said at the unveiling, Sherald’s work will have impact on “girls and girls of color. … They will see an image of someone who looks like them hanging on the wall of this great American institution. I know the kind of impact that will have on their lives because I was one of those girls.”

Looking at the paintings, President Obama talked about art that can picture the “beauty and the grace and the dignity of people who are so often invisible in our lives, and put them on a grand stage.” About those people, he said, “Kehinde lifted them up and gave them a platform and said they belonged at the center of American life.” Amen. Then he casually mused that as far as he could tell he and Michelle were the only people in their family trees to ever have official portraits made. These four firsts and the big picture they represent transcend small talk about any little details of the pictures and let us resume our search for delivering America from its current moral, spiritual, and political disarray.

*A version of this article appears in the February 19, 2018, issue of New York Magazine.