Behold the artist Frank Walter at the booth of Hirschl & Adler Modern at the wonderful 2018 ADAA Art Show. Walter was born in Antigua in 1929, a “very dark-skinned” descendant of a white slave owner and a black slave. He struggled his whole life with his racial identity and was the first black child in a special all-white Antiguan school where he mastered and excelled at Latin, French, English literature, algebra, geometry, chemistry, botany, geography, history, art, and music. By 1948, as labor unions were transforming slave conditions on sugar plantations, he was the “first” black manager of a major plantation. He called himself a “Europoid” — his term for a race of transplanted colonial Europeans — and said he was “sun-kissed.” The poetry of these terms is still powerful, even as — or perhaps because — we can now see that by using them he meant to signal that he thought of himself as white.

In 1953, Walter and the love of his life Eileen Galway set sail to London for a planned ten-year European Grand Tour: nothing but love, ambition, and promise was on the horizon. Yet by the time he died, in 2009, he had spent the last two decades of his life living alone, dirt-poor, in a shack without running water, electricity, or access to roads, on the side of an Antigua mountain. Here, rocketing between brilliant insight, wild imagination, full-on hallucination, and fits of delusional grandeur he produced an epic series of almost entirely unseen work — including a 25,000-page typed manuscript on philosophy, history, art, geology, and biology; numerous plays, poems, musical scores; and hundreds of hours of recorded audiotape. He also made over 5,000 sculptures, paintings, drawings, diagrams, cosmic charts, and heraldry designs on cardboard, wood panels, old photos, the backs of album covers, paper bags, planks, metal signs, and any surface he could scavenge. (All of this would likely have been lost were it not for art historian Barbara Paca happening upon his work in Antigua at the very end of Walter’s life, and seeing genius. In 2017, Paca oversaw Walter being named the representative of Antigua and Barbuda at the Venice Biennale.)

Fixated on the white side of his family, Walter declared himself a royal descendant of both Charlemagne and King Charles II (see the many fabulous genealogical charts) and dubbed himself “Seventh Prince of the West Indies; Lord of Follies; and the Ding-a-Ding Nook.” He was a genius, an artist who — like Henry Darger, Adolf Wolfli, and Emily Dickinson — traversed the universe and explored the darkest hollows of the human psyche, arriving at an incalculably reverberating body of work. He should be collected by all museums. His story proves that in the same way that many of the best artists of the 1930s and 1940s went up the chimneys of concentration camps and died on the battlefields and that many of the best artists of the 1980s were lost to AIDS, so too generations upon generations of African geniuses were lost to slavery, colonialism, and its aftereffects. The consequences for art history were even more devastating in this case, as the devastation lasted 500 years — in fact, lasts still.

Unlike James Baldwin, who went to Paris in 1948 and experienced less racism, Walter felt the full weight of prejudice fall on him all at once in Europe. I surmise he was never the same again, that everything he subsequently made stems from the psychic and physical violence he suffered there. In August 1953, he and Eileen arrived in London to begin their tour of Europe. They were met by an aristocratic uncle of Walter’s. There on the sidewalk the uncle embraced “the beautiful passing-for-white Eileen” and ushered her into his home and to a new life. He left Walter alone on the sidewalk; Walter never saw his beloved again. She went on to become the first Antiguan barrister in Great Britain.

Nevertheless, alone and forsaken, Walter set out to make his way. After all he was highly educated, especially in advanced agriculture — a brilliant scholar and researcher. However, he found no one willing to employ a black man. Still undaunted, he began working at maliciously low wages at unskilled hard-labor jobs across England, Scotland, France, and Germany. He was a factory worker, coal miner, swept floors, unloaded hot kilns, and labored in boot and lamp factories. He was slowly starving to death and eventually fell prey to swindlers. He was then robbed and beaten. As Baldwin said, the madness of racism was “created deliberately … white racism is at the bottom of all of it all … and it will rise up to smote us all.” By 1960, it smote Walter. Derided, detested, cornered, and disinherited of his birthright, his love, and his inner sense of self, he was placed in a “nerve hospital.” The only lights left would be going home and art.

In 1961, he went back to the Caribbean, this time to the island of Dominica about 100 miles south of Antigua. There he reclaimed 25 acres of land that belonged to his family. He laboriously hand-cleared giant hardwood trees and soon began farming successfully and writing, recording his thoughts and making things. Then the long arm of colonialism reached out. The corrupt Dominican government was bribed by a massive sugar plantation and took away Walter’s land. That was that.

In 1967, he returned to Antigua, broken, and cobbled together a life. He wrote that he was now “able to change my natural color to White … [to] lead one to believe that one had seen a White person.” As Frantz Fanon wrote, “Incapable of integrating, incapable of going unnoticed, [the black person] starts conversing with the dead and the absent.” That’s Walter. In 1995, however, providence moved one last time and shined a light on him. He found an abandoned shack on the quiet side of the island, settled in it, and finally immersed himself in his writing, composing, and his art. In 2009, he died there after a short illness. What he left behind suggests that he is among the great visionaries of the late-20th and early 21st centuries.

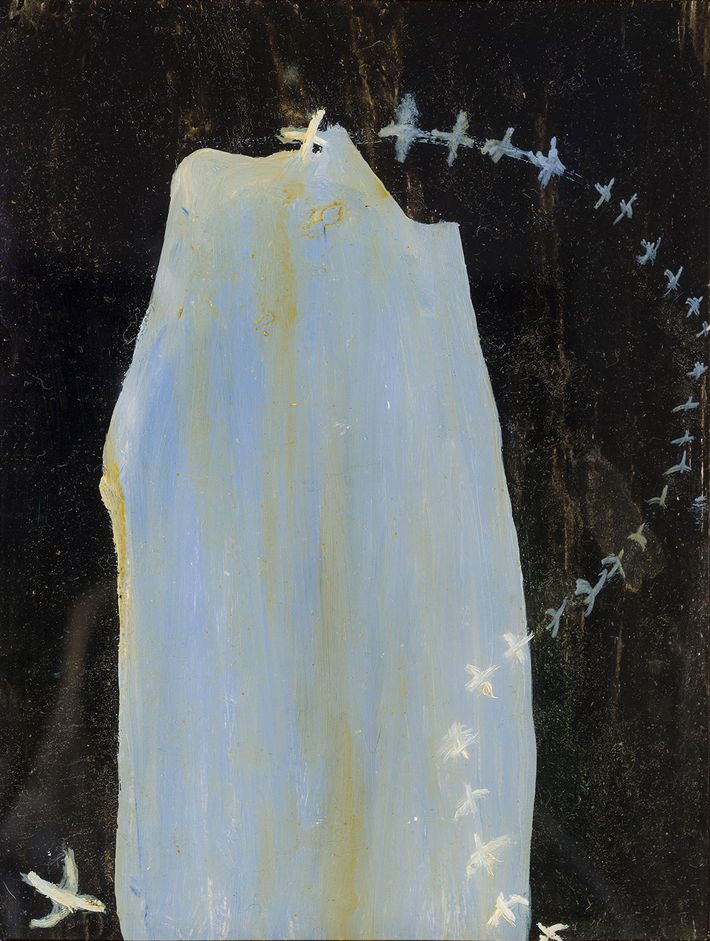

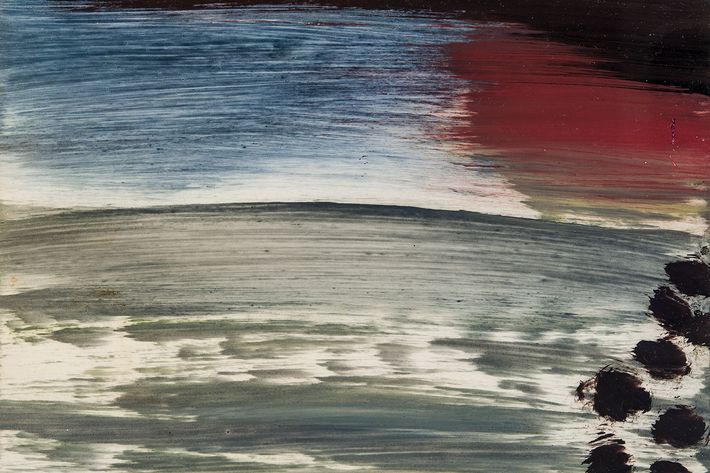

The sampling at the Armory is enough to immerse us in Walter’s world. His colors are beautiful, glowing, opaque primaries, pastel yellows, reds, blues, cream, and thalo greens. His touch is careful — he knows what he’s trying to depict; surfaces are scumbled, rough, and awkward, like his mind is moving faster than the brush — his hand trying to keep up, get it all down. He also paints foggy or iridescent washes with tissue-like attention to changes of brush direction. It’s impossible when looking at his work not to sometimes think of modern artists like Cocteau, Picasso, and Kandinsky, as well as contemporary artists like Chris Ofili, Peter Doig, Chris Martin, Nicole Eisenman, even Mary Heilmann. A startlingly abstract image of geometrically divided stars within faceted, colored circles instantly suggests the visionary greatness of my all-time favorite American 20th-century painter, Marsden Hartley. Indeed, Walter gives the work a title that Hartley would have understood: “Psycho Geometries.” We see jet-black faces that recall Kerry James Marshall. There are strange Whistler-like nocturnal scenes of seasides and waves. A mystical series titled “Meditative Patterns” pictures dot-patterns of crowns, hearts, birds, spiderwebs, and petroglyphs. Racism might have pushed Walter over the edge, but it didn’t kill his art, his vision, or his inner sight.

His titles can be great: “Black Demon,” “Ascending Heaven’s Steps,” “Jesus Comes to Antigua,” “Fourth Dimension,” “Photons,” “The Right Side of the Milky Way Galaxy.” He painted a portrait of Hitler and one of Adam and Eve as Prince Charles and Princess Di. A gut-wrenching portrait pair depicts his long-lost love Eileen and his own self-portrait, in which he is white. He’s in a tuxedo and dapper here. He wrote that he “walked Cary Grant and had a ducal demeanor.” “Coconut Woman” is a sweet brown-skinned woman with coconuts over her breasts. Walter loved it all. He was Whitman-esque in his overflow. He painted black swans (he wrote “I was now a Lonely Bird … spreading my wings from field to field”), weather patterns, gulls, still lifes, sailboats, plantation fields with workers, palm trees, hurricanes, tide pools, inlets, rain, water spouts, feeding fish, houses, hillsides, galactic pictures, abstractions, scientific illustrations, signs, mountain passes, and castles.

Walter never found the recognition he was looking for; he yearned to have his work seen and acknowledged in his lifetime. He badly wanted to be integrated into art history and resume his rightful place in the world. But as Baldwin observed, does one “really want to be integrated into a burning house?”