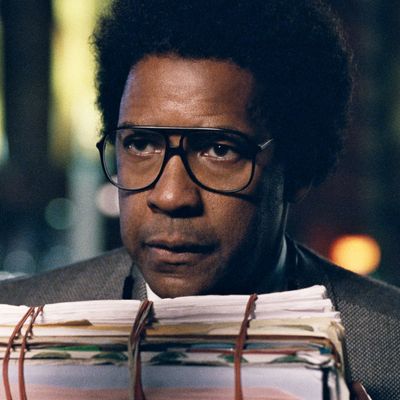

Producer Samuel Goldwyn once said, “God makes the stars, it’s up to us producers to find them.” Goldwyn frames stardom as mythic, divine, a matter of unquestionable chemistry. History has proven otherwise. Stars — the supernova, easily recognizable breed, with clearly defined images and audience relationships — are in short supply in Hollywood, which has been bemoaned for years now. Denzel Washington is unquestionably a star who, in the course of his cinematic career, which began in 1981 as an actor and occasional director, has done what all great stars must to be valorized as legend: captured the cultural mores of the moment, made artistically bold choices with a blend of familiarity and reinvention, and filled a void in the cinematic marketplace. Excellence is, at this point, a state of being for Washington. He’s played slick private detectives traversing postwar Los Angeles and madmen with badges to mask their impropriety. He’s played political icons and common men, saints and sinners. Washington’s greatest gift as an actor is how he portrays anger, giving it a considerable weight that shimmers with historical resonance. It’s an anger that seems to fit along an arc of black identity, as if considering its personal dimensions and cultural ones. But what Washington has never been onscreen, at least fully, is awkward and unsure. Until his tremendous performance in writer-director Dan Gilroy’s Roman J. Israel Esq.

Roman J. Israel Esq. is a film mired in an identity crisis. While it was marketed as a ’90s-era throwback to stately legal dramas, as Marya E. Gates says in her review of the film, the film is a different beast altogether. It’s more of a noir, built around a concept common to the genre: A relatively good man is undone by his hubris and materialism, sacrificing his morals only to be crushed by the machinery of the larger system he originally fought against. It’s the story of a man losing his soul. The man in question is the titular character, played by Washington. He’s a dedicated, even hopeful civil-rights attorney with genius-level intellect who is clearly on the autism spectrum. After Roman’s longtime partner, who was the face of their legal practice, has a heart attack that lands him in a vegetative state, his life unravels. Roman continues on uneasily at the firm of George Pierce (a beautifully shot Colin Farrell), who sees Roman’s incredible knowledge of the law as an advantage and also takes pity on him since his former partner was a mentor of sorts.

While Washington’s performance was mostly praised, the film itself was seen as a failure. It lacks the slick, propulsive immorality of Gilroy’s directorial debut, Nightcrawler, but it is held together by a thoughtful warmth that radiates from Washington’s embodiment of this character. It’s noir by way of character study. And the character allows Washington to coax new dimensions out of his star image.

One of the greatest and most underrated gifts an actor can have is the ability to actively listen. This is something Washington excels at, which is what makes his performance as Roman so intriguing. Of course, when you look at Roman, there is an obvious transformative aspect (although not as dramatic as Oscar-nominated roles like Gary Oldman’s turn as Winston Churchill, which is seen as the Best Actor front-runner this year). Washington face is haloed by an uneven Afro, he wears caps on his teeth to give Roman a gap-toothed grin, and his clothing is sloppily put together. But what’s most transformative and moving is how Washington listens and looks at the world around him. Roman often doesn’t look people in the eye. His gaze is furtive, unsure. He doesn’t seem to listen wholly to people. Washington, through subtle tics in gaze and gesture, communicates effortlessly what Roman is thinking, constantly reassessing his place in the world and what to say to survive.

Early in the film, after his partner’s heart attack, Roman goes to court to handle his continuing cases. He grows combative with the judge — he feels his client’s civil rights were disregarded and that deserves to be brought up even before trial. His gaze still fixed downward, he says, “With all due respect you’re asking me to obey an erroneous court decision and asking me to wait…” before a gavel cuts him off and he’s held in contempt. In a conversation about the role with Gilroy, Washington says he did considerable research on Asperger’s and mimicking neuroatypical behavior. This is evident throughout the film in both grand and fleeting moments — failed courtroom appearances, shrinking under the critical gaze of colleagues, studying himself in the mirror, a futile job interview with Maya Alston (a wonderful Carmen Ejogo) for a local activist organization he feels suited for. Washington plays Roman as a man trying to replicate the rigors of a world he doesn’t quite understand.

This feels subversive because Washington often plays characters with immense command of themselves, who understand how to move through the world. They’re charismatic, with a blend of ease and intensity. Roman is the antithesis of this. He’s a man out of time. He is cut from the cloth of 1960s activists, with the same ardor and sense of self-sacrifice. His work is admirable, his intellect unquestionable. But he fits neither within the current milieu of the younger generation of activists nor the lawyers he knows as his colleagues.

The most explosive scene in the film considers this dynamic, when Maya invites Roman to speak to a group of young activists. They first seem intrigued by his advice and his reckoning with history, as a living embodiment of a civil-rights era that seems foreign to them. But the conversation quickly goes awry when he chastises a few young men for not letting the women standing on the sidelines sit down. “This isn’t 40 years ago,” one young woman notes derisively. They become a bit more vicious considering Roman’s etiquette is sexist rather than chivalrous. Washington becomes flustered, as if uncomfortable in his own skin. You can see his eyes dim as this moment becomes another reminder of his inability to find a place in the world around him.

Moments after his tense confrontation with the young activists, Roman and Maya discover what they think is a dead homeless man. Roman slips his card into the homeless man’s pockets in hopes he won’t be cremated and his remains anonymously tossed aside. (As it’s explained in the film, if someone doesn’t have identification on them when they’re found dead, the state decides what to do with them, which means they’re cremated and their remains discarded.) It’s a genuinely sweet impulse, and it’s this feverish quality to his pursuit of justice — particularly for the people wider society refuses to see humanity in — that makes his later failures so galling, when he makes a fatal decision, sacrificing his strict moral code on the altar of materialism.

After one of his clients dies, Roman decides to use his knowledge about the man who actually committed the murder (his client was unfortunately roped into being an accomplice) to gain the $100,000 reward anonymously. It’s fascinating watching Washington portray Roman as a man who wants to embody the typical sleek lawyer who traded his soul for a fine three-piece suit, but is unable to fully inhabit this due to the pieces of his soul that remain, and his autism. There is an unfiltered joy that marks his face as he buys decadent donuts and eats them on the beach. He wades in the water with a delight that seems almost childlike, as if experiencing these cool waters for the first time. But soon enough, he uses the money to refashion himself in the image of the kind of lawyers he used to abhor. He slicks his hair back, revealing his curl pattern. He wears a resplendent suit. He goes out with Maya, taking her to a lavish restaurant he is uncomfortable at. Roman seems uncomfortable in his new guise despite wholly giving himself to it. The film begins in a way that echoes Double Indemnity — Roman writes a legal brief condemning himself as a human being and asking to be disbarred. It’s clear after a certain point, even after he decides to turn himself in, that Roman won’t survive.

Before the violent conclusion of his life at the end of the film, Roman tries to make amends with George, who by now knows what he did. He says, “I’m going away,” launching into a consideration of this frightful chapter in his life. Washington’s voice moves between regret to something at the pitch of a sermon. Through Washington’s skill, this conversation is more than just a good-bye — it’s as if Roman is giving his own eulogy. Later, there is a palpable sadness weighing on his shoulders as he talks to George while navigating the crowded Los Angeles streets. The way he speaks of forgiving himself and the awkward laughter that prickles the conversation, it’s clear that Roman actually doesn’t. He knows he’s failed. And this failure is not just personal, but historical. It’s as if his sadness reverberates with the weight of black American history itself. He’s failed not just himself, but the people he marched with, the clients he vowed to protect to the best of his abilities. I have found myself quite haunted by Washington’s performance, particularly its most minute moments. His crooked smile saying good-bye to George, the way he plays off of Ejogo’s tender performance, the careful way he picks out his Afro in front of a mirror.

Washington has a slim shot at winning Oscar gold this weekend. Oldman as Winston Churchill in Darkest Hour is positioned at the front-runner with a narrative about his win being long overdue. If there will be an upset, it will likely be Timothée Chalamet’s tender performance in Call Me by Your Name. A recent Hollywood Reporter article framed Washington’s nomination as a “knee-jerk response” to a “great career,” an emblem of the old guard the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences needs to move away from. This does a disservice to Washington’s immense performance, which is tender, heartfelt, and layered. It’s fascinating watching Washington operating at such a different tenor than the rest of his career — reveling in a sloppy awkwardness that reveals the intimately human dimensions of civil-rights activism, criminal justice, and the desire to fit in a world that refuses to understand you.