Santiago Ramón y Cajal is one of a kind in more ways than one. He is the only Nobel Prize winner in history — in physiology and medicine, 1906 — to also be a truly great artist. Cajal (pronounced Cah-hal), whose work in his field can be compared to Charles Darwin and Louis Pasteur in theirs, is also among the best draftsmen of the 20th century. If his penciled linear, fractalizing networks and abstract webs were inserted into any art museum’s early-20th-century permanent collection they would stop people in their tracks and vie with the best the museum has to offer.

But this will never happen, as museums are still relentlessly, even recalcitrantly set on telling only one mostly formalist story of one very narrow branch of visual practice over a delineated time frame from a very limited geographical area. This story, according MoMA and almost all art-history books, starts with a sort of inviolate Old Testament: In the beginning there was Cézanne who begat Picasso, Braque, and Matisse who begat Duchamp who together begat Mondrian, Italian Futurism, and Russian Constructivism and Suprematism which begat Dada, Surrealism, and German Expressionism all the way down the line to Pollock and De Kooning who begat all the rest. This mostly male European-American juggernaut is not only the reason that MoMA’s permanent collection at the turn of this century was less than 8 percent women and that walking through museums is now akin to tuning into classic rock with the roles of Led Zeppelin and Fleetwood Mac being played by the aforementioned “masters,” it is the skewed institutional-academic apartheid that has all but suffocated art history by systematically excluding oddballs, aberrations, visionaries, and all those who were not trained as or who didn’t primarily identify as modern artists. To this day, most permanent collections exclude geniuses like Bill Traylor, Adolf Wölfli, Martin Ramírez, Henry Darger, to say nothing of Gee’s Bend quilts, Hilma Af Klint, Emma Kunz, Marsden Hartley, Louis Eilshemius, George Ohr, James Castle, Forrest Bess, Jess, Jay DeFeo, Ray Johnson, Jim Nutt, Asger Jorn, Beauford Delaney, Bob Thompson, Robert Colescott, Oyvind Fahlstrom, Konrad Klapheck, Paula Rego, and H.C. Westermann. This is the apartheid that forbids including anything like nature or scientific illustration, visual work that doesn’t fall in the exact formalist ontological predefined lineage. We may allow Picabia’s diagrams and Twombly’s squiggles to be art but not those of Cajal. This needs to change.

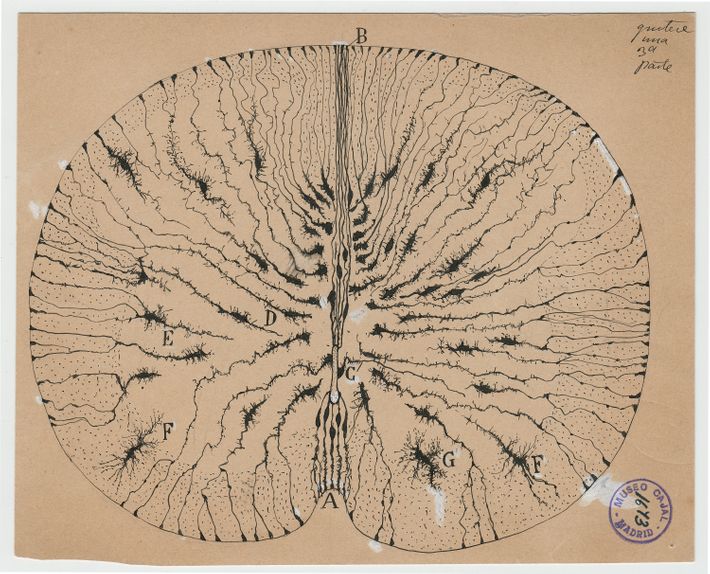

No matter. For the first time ever in this country — and likely the last — over 80 of Cajal’s small masterpieces are on view at the Grey Art Gallery. It is perhaps the only exhibition of 20th-century drawings I can imagine that might be compared in any way to this season’s duel graphic blockbusters of Michelangelo at the Met and the full-on Twombly drawing survey at Gagosian (a review will follow in the near future). As with Michelangelo, Cajal revels in the deep wonders of the human body. But where the Renaissance master goes sensual, macro, and dynamic, the Spaniard zeros in, mapping the miraculously microscopic using new methods of staining slide tissues that isolated single cells under the microscope. In this way, Cajal drew the newly visible synaptic networks of the brain and discovered a breakthrough that proved that neurons are in touch without touching. These results changed neuroscience. His work is still widely used as a teaching device.

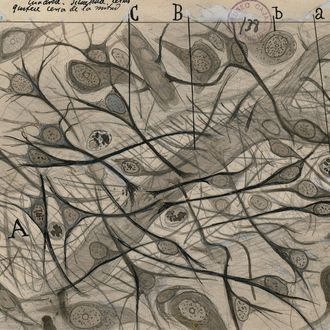

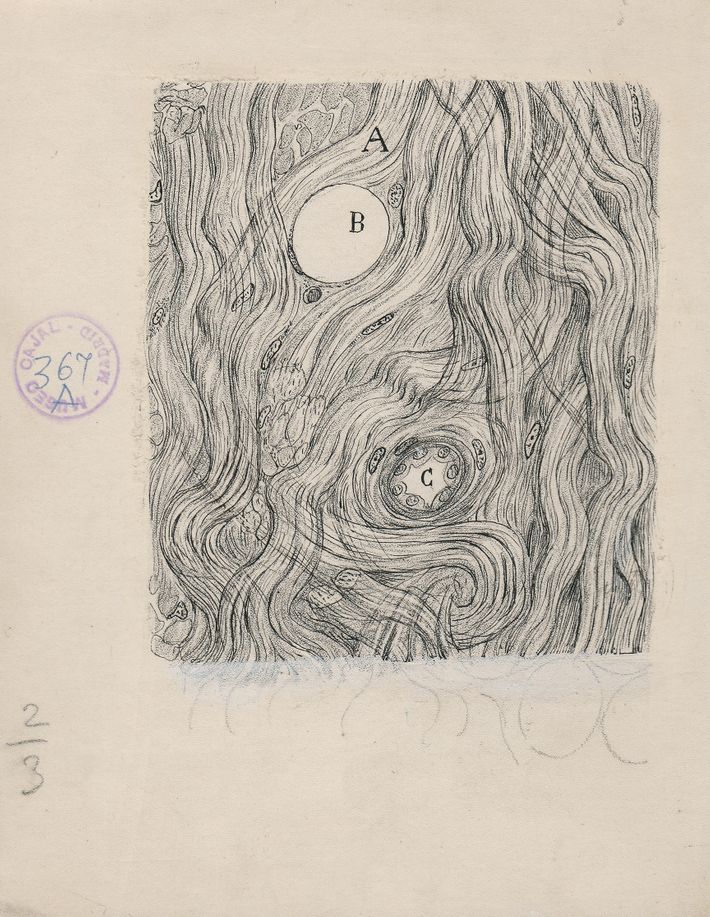

The drawings can change lives. Looking like complex crisscrossings, fracturing thickets and lines, they can resemble animal architecture, nests, hives, canal or root systems, weather patterns, contour drawings, wind vectors, seed structures, riverbeds, ravines, and galaxies. The closest art equivalent to Cajal’s drawings are Leonardo’s weather and water deluges. Da Vinci saw the world outside. Cajal gives us the forces at work within us. You look at them and think, “That’s me.” This is followed by an otherness that reverberates with incredulity at the weirdness that this lightless world of interconnected colonies of corpuscular blobs and dollops are, at the core, what we are. Cajal renders this spatial-conceptual infinity with constant loving attention paid to touch, lightness, darkness, clarity, space, surface, scale, visual beauty, and 100 other aesthetic values that allow us to begin to know the world in ways that are as much art as Leonardo’s drawings of dissected human bodies are also functional anatomy drawings. As with Michelangelo, Leonardo, and Twombly, Cajal is inventing a language beyond words, that slows and deepens perception, that multiplies our grasp of the world, explores consciousness and changes it! If this isn’t art, I don’t know what is.

We almost didn’t have Cajal the artist at all. His parents forbid him to draw at home, saying it was “a sinful amusement.” So, secretly, he went outside to draw the fields, flowers, and fauna around his home in northwest Spain. Here he crafted his epic powers of observation, ethereal touch, and tonal fields. Cajal has an eye for pattern, structure, texture, complexity, shading, delicate washes, and an unreal sensitivity to the pressure of his pencil. It’s like looking at the ghostly penumbra of a Seurat drawing. The confrontation with his work isn’t like looking at scientific illustrations at all. Nor is it like any of the high-key colored and ultimately inert new HD, multi-neon-hued renditions of electron microscopes. In Cajal we see the presence of splendor, a structural mother tongue that allows information to pass itself along in spectacular arrays that look to us like great abstract art.

His titles are fabulous. “A Nerve Stump of the Rabbit Six-Hours After Damage,” “The Hippocampus,” “Muscle Cells From the Leg of a Scarab Beetle,” “Synaptic Contacts in the Cerebellum.” Cajal breaks these drawings down into individual cells, neurons, synaptic contact networks, and gives us fibrous biomorphic forms trellising in organically asymmetrical ways. We see chemical and electronic information crossing circuitry, routed into and out of burl-like nodes, branching trees, and tributaries connecting contiguous weavings. Looking at Cajal’s work you wonder if the structure of the brain might be the only thing as complex as the universe itself. Especially as you ponder how these microscopic environments control everything about life — from tears and saliva, to allowing us to hear and see, to keeping our balance and our heart beating — that together with all these other cells and networks allow us to feel loss, love, pain, write the Iliad, invent the computer, conjure gods. Art lovers will revel in connecting Cajal’s work and scores of other contemporary, modern, and older artists. Cajal’s gorgeous drawings let us see profundity.

*This article appears in the March 19, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!