The first time I saw Cy Twombly’s aphrodisiacal paintings, I felt the way Patti Smith felt when first hearing the Rolling Stones: “I was doing all my thinking between my legs.” Something unrecognizable and distorted within me quivered. Twombly’s fevered phosphorescent blooms of runny jellyfish chrysanthemums with elongated, pulpy, tentacle-like sacks dripping down; his iridescent storms of inchoate cryptographic scribbles, floral scrawls, jittery jutting lines; pustules rising and falling like raw nerve endings, flying vagina dentata, plaited anuses, priapic phalli spouting involuntarily or drooping defenseless, and what his closest reader, MoMA’s late Kirk Varnedoe, called “anteater tongues” — all of it metamorphosed into my own inner Kama Sutra of urge. Sensory networks lit up; a new barometer fluctuated. It was abstract yet explicitly erotic. I was in voluptuous rut. But something like gravitas and immensity was preponderant within me, too.

Somehow, by deploying only the barest rudiments of art — jots, dots, lines, doodles, dashes, loops, scribbles, scratches, little glyphs, weird ruins, rising Gothic skeleton structures, ziggurats, wobbly frame shapes, and (perhaps more effectively than any Western artist who ever lived) hard-to-read handwritten words and phrases, whole poems, and the names of ancient poets and places — Twombly has been able to make an art that rises to the level of epic poetry and fills you up with the sweep of history and fiction. He’s one of the few 20th-century painters who produces some of the same capacious sensations we get while reading Virgil, Homer, Sappho, Keats, and others. A silent sonorous world opened. Twombly brings mythos and antiquity together with Smith’s “thinking between my legs,” and an undertow of the elemental interiority and abjection of Francis Bacon.

Right now there are two spectacular Cy Twombly shows at Larry Gagosian Gallery. (None of the work is said to be for sale, so … thank you, Larry.) Uptown are the stately so-called “solar-barges of the sun”— the ten-part painting cycle from 2000 titled “Coronation of Sesostris.” (It’s the second time it’s being shown: The group was installed almost exactly this way on the same walls that year. For whatever reason, Twombly changed the third painting, and I liked it more before he did.) “Sesostris” is ostensibly based on the stories of three 12th-dynasty Egyptian pharaohs by that name. But just the arcane Egyptian word conjures obscure twinges, the physiological effect we feel when gazing at hieroglyphics. This wraparound room-filling undertaking finds the then-73-year-old artist developing and deploying the multicolored fireballs, ship prows and oarsmen, smears that look like waterfalls, and giant floating clots that had been appearing in his work since 1987. In this tour de force, Twombly, who died in 2011, was reborn once again and began putting all this together, commencing the colossal final years of his work.

The 50-year concatenation that led to all this is on view in the equally unmissable 21st Street show. In almost 100 works dating from 1951 to 2008, it gives an account of Twombly’s ever-changing drawing methods. His hand is a Geiger counter of indefinite interior synesthetic sensations that break the surface of painting and telepathically distend into us. This huge show begins with a table laid out with a series of small notebook pages from 1951. Here, at 23, Twombly sketches cage, grill, grid, window, and fence-like configurations with sprigs and sticks, nodes and nodules affixed to rickety, stiff lines. Already he’s using marks and structure to get around Abstract Expressionist gesture and Gorky’s biomorphic composition, and even looking past not-yet-extant Minimalism to something stranger and more personal. That was the year after Twombly had met his then-lover, that fellow Southerner Robert Rauschenberg, who brought him to Black Mountain College, where he met Jasper Johns, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Charles Olson, and many others. Twombly and Rauschenberg soon traveled together to Naples, Palermo, Rome, Florence, Casablanca, Tangier, and Morocco where they met and traveled with Paul Bowles. These first drawings also show Twombly already internalizing the inspiration that Rauschenberg seems to have imparted to all those who came into contact with him in those days. Indeed, careful readings of Twombly’s career suggest that almost every time the two had sustained contact — even long after they ceased being lovers — Rauschenberg’s titanic talents caused Twombly’s work to explode. The final drawings in the 21st Street show are the ecstatic last blasts and Whitmanesque effusions that flowed into Twombly’s paintings and drawings at the end.

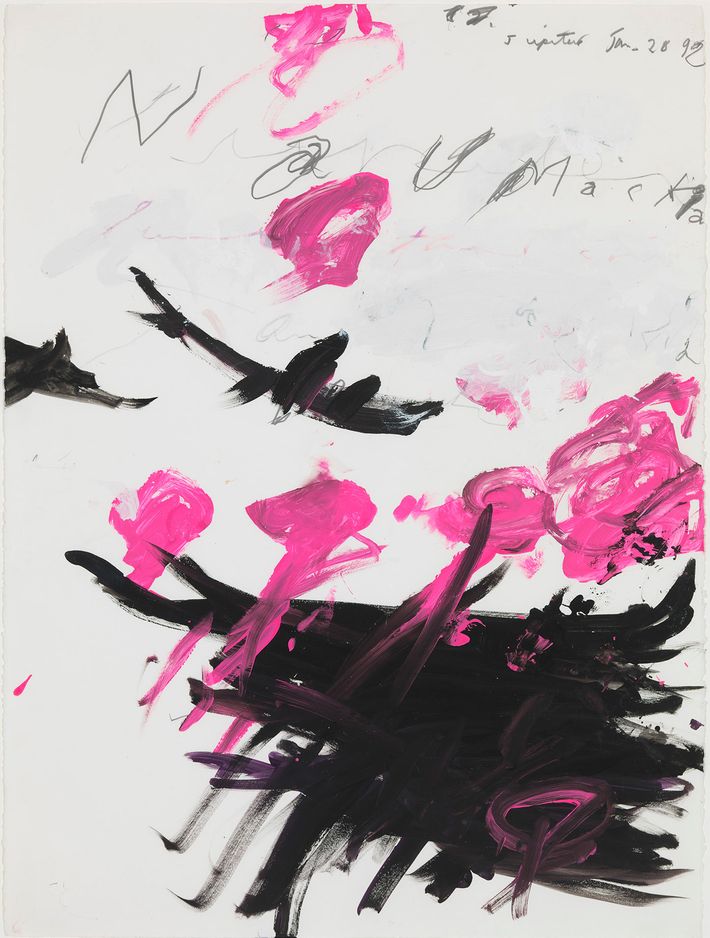

To consider just two beauties from 1992, both titled Naumachia, note the arc-shaped boats, the idea of the canvas imposing some enclosed sea, ships sailing, maybe magnolias blooming, a feeling of a violent order being disordered at the same time an essential unity is portrayed. Naumachia is an ancient Greek word that means “naval battle.” In Rome, however, the word came to mean the gigantic war games staged as mass entertainments in flooded coliseums and arenas. Julius Caesar once deployed more than 2,000 combatants and 4,000 rowers, all prisoners of war, to restage one of his recent victories. Twombly suggests that on a formal level, at its core, this is what all painting is — a willed staged presentation within artificially imposed borders where imagination, chance, order, intention, experimentation, audacity, and ideas are all put into play and are meant to captivate.

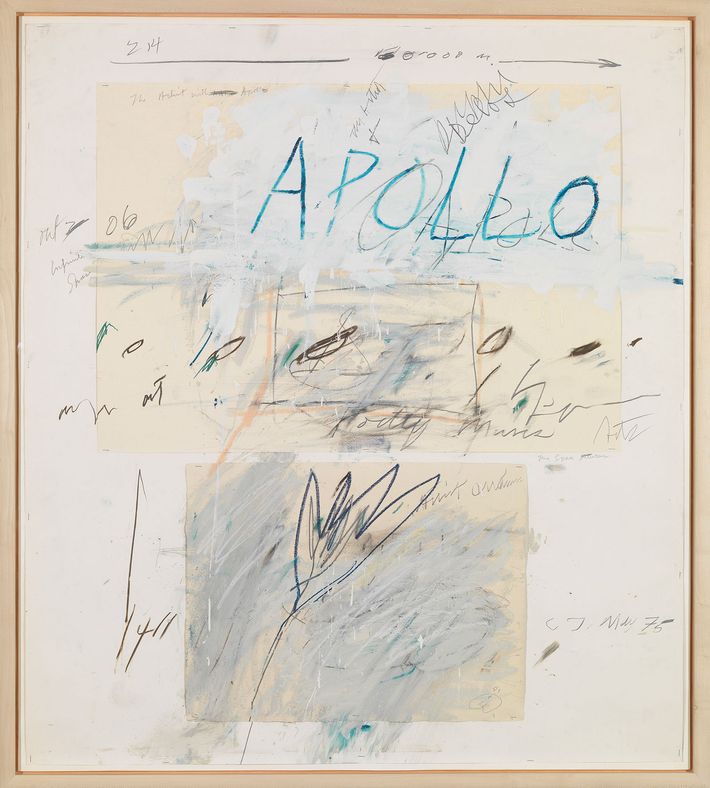

To grasp just how much experimental and staged pictorial and graphic information springs from Twombly’s drawings, recall that immediately after the 19-year old Jean-Michel Basquiat saw the 1979 Whitney Museum retrospective — which included several of these exact drawings, notably Apollo and the Artist, in which the words “Apollo” and “artist” appear on a surface surrounded with free-floating notations — Basquiat aesthetically detonated and began making his own assembled works with words, graffiti, crowns, arrows, and names. In this genesis moment he took Twombly’s speed of history and amped it up to the speed of life. In that same Whitney show Basquiat saw the beautiful Ode to Psyche, with its great arch at the bottom of the page, counting numbers enumerated, flying words and phrases like Keats’s “kiss to outnumber, at tender eye-dawn of Aurorean Love.” Feel the luminous atmospheric streamers and charged particles that must have ignited in Basquiat’s mind in the same ways that Twombly must have experienced Rauschenberg. I fancy young artists coming to this show and extending that arc.

I’m not going to delve into the encyclopedic trove of aesthetic possibilities implied in all these drawings. I only urge viewers to suspend thoughts that Twombly is just some charlatan wisenheimer trying to put one over on you. Don’t place yourself in this cynical cul-de-sac — it’ll restrain your mind and eye from wandering far enough afield to grasp Twombly’s gigantic indexical range. Allow shapes to congeal into narratives, temples on fire, tidal waves washing over inscriptions, chariots on the plain, Leonardo-esque deluges, bed sheets after lovemaking, burial mounds with flowers stuck in them, and panoramic battle scenes with armies of marks surging or being wiped out in erasure. Let Twombly’s eroticism, formalism, and visceral brio reach you. Accept the gall and glee of titles like Leda and the Swan, School of Athens, In Beauty it is unfinished, Delian Ode, Hero and Leander, or The Battle of Lapanto. Let Twombly’s way of redefining skill redefine your ideas about skill too.

Back uptown, “Coronation of Sesostris” moves from left to right in different sized and shaped large canvases arrayed around three walls. (A careful study of Twombly’s drawings reveals that he first drew this “solar barge of Sesostris” motif as far back as 1985.) Consider the whole as a retinal-emotional musing on the soul’s journey to the afterlife — on loss, glory, love, homesickness, painting, or just a passing Proustian dream. We see barges in the shape of closed eyelids with what look like oars sunk in water like eyelashes; we see wobbly suns rising high and setting low. The last canvas has a blocky top-hat shape that might be derived from a figure Degas painted of his brother, Achille, in 1873’s The Cotton Exchange in New Orleans. (Even if it isn’t based on his brother, we might savor the possible connection to the name of a Greek hero.) The overall palette is white-primed canvas, with tones of saffron mustard, lemon-yellows, purples, violets, ruby and rose-madder reds, and Turneresque washes of glowing color. Words drift in and out of focus; none are easy to read; all make you nearly chant them aloud.

You can see them in any order. The sixth canvas looks like a page from a book and has two-dozen blood-red glops around the stabbing words of American poet Patricia Waters that read, “When they leave do you think they hesitate, turn and make a farewell sign, some gesture of regret.” Soon you make out “the sun is high … you dizzy with wine, befuddled with being, sink into your body, as though it were real … yours to keep.” There’s a real sense of trying to hold on to life, love or memory. The penultimate canvas is a black-outlined lone boat and the phrase “Leaving Paphos ringed with waves.” Paphos is located on Cyprus, also known as the “Island of Love,” the supposed birthplace of Aphrodite. The cycle transmutes into some sort of final farewell. The second canvas finds the words “Solar barge of Sesostris” hovering over an image of a double sun. In the last Degas-inspired panel, all the color has drained as we read Sappho’s aching refrain: “Eros weaver of myth, Eros sweet and bitter, Eros bringer of pain.” Thus Twombly has given us rising and setting suns, the passage of a day or a life or an era, ships ablaze on flowered grounds, and this final call to psychic and physical shore. The cycle is complete. All that remains is every nerve in your body straining with this overload of irrational beauty, desire, mannered pretension, incipient need, esoteric information, cryptic incantation, and what look like bird footprints run through milky paint to some further Mediterranean shore.

“Coronation of Sesostris” is on view at Gagosian Gallery, 980 Madison Avenue, at 75th Street, through April 28. “In Beauty it is finished: Drawings 1951–2008” is at Gagosian’s 522 West 21st Street location through April 25.