Outside of the Bible, it’s hard to think of an origin story retold more often than that of Batman. Created by Bill Finger and Bob Kane for 1939’s Detective Comics No. 27, the character didn’t get a formal backstory until the 33rd issue of that series the following year, written by Finger and Gardner Fox and drawn by Kane. In a few cramped panels, it told the tragic tale of Bruce Wayne, a rich kid who witnessed his parents’ murder, swore to fight crime as vengeance, trained to physical perfection, saw a bat fly through his window, and decided to adopt a cape and cowl as a “weird figure of the dark.” Since then, we’ve seen near-countless versions of this story on the page and on the screen.

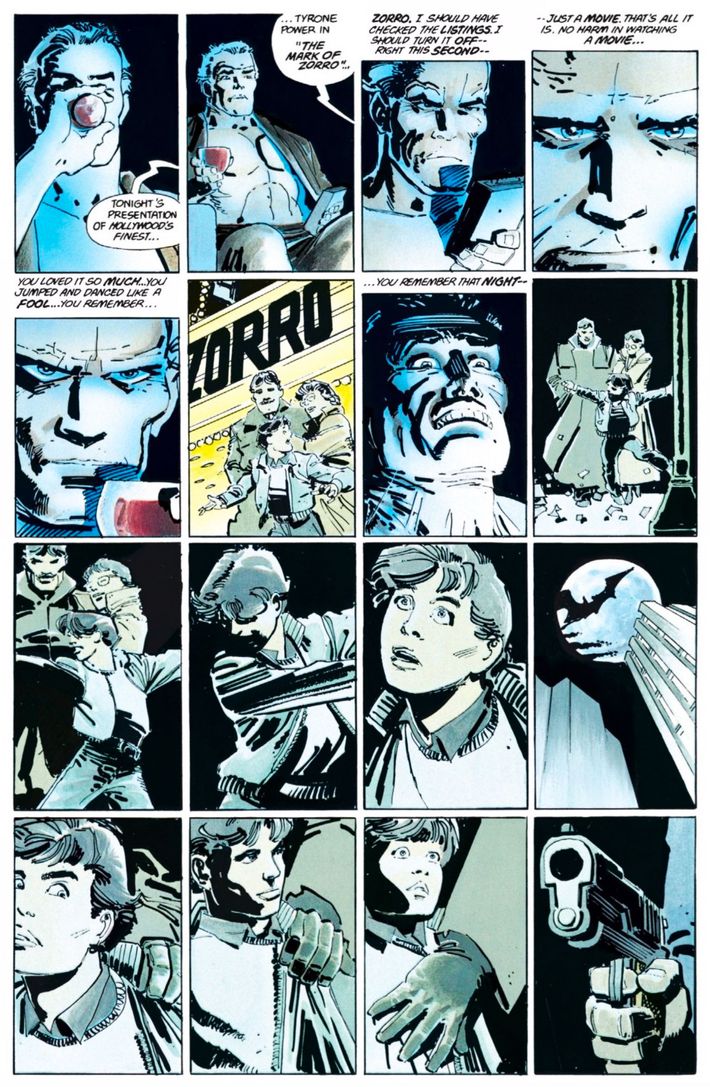

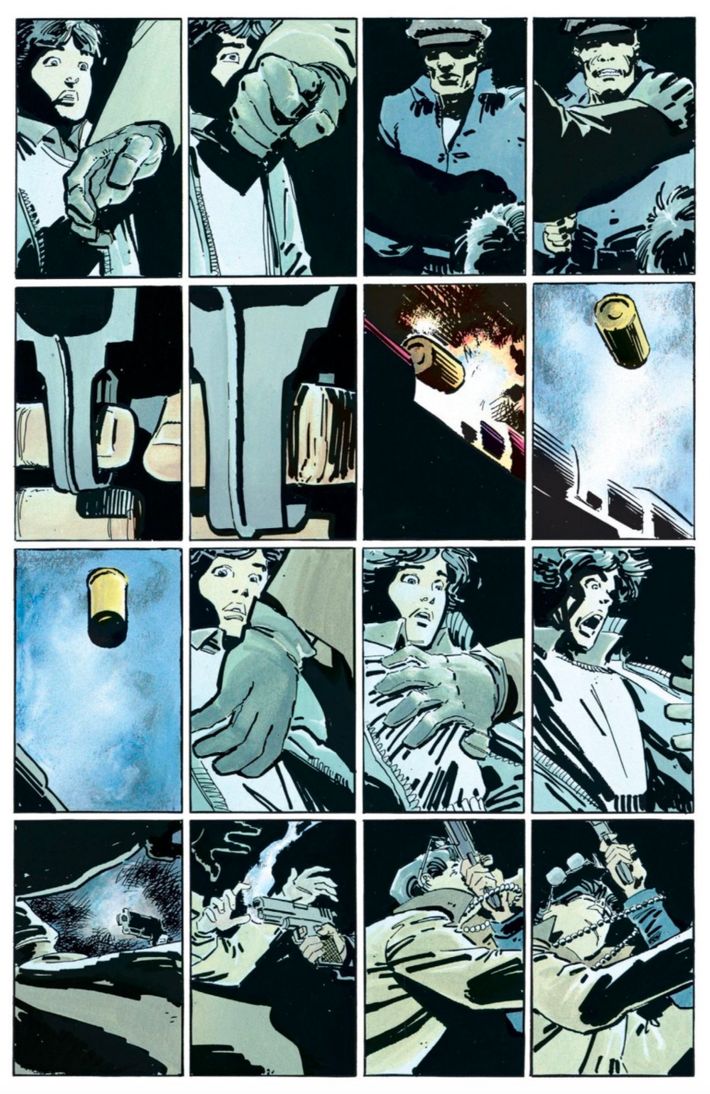

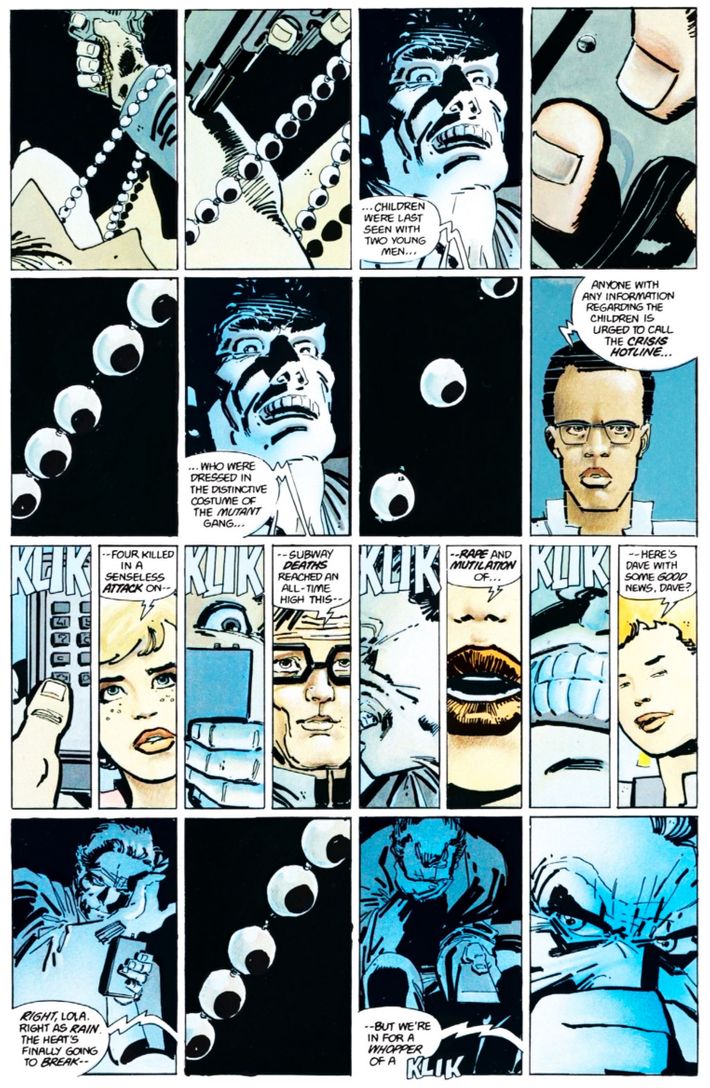

But of all those retellings, none has had more creative oomph and long-lasting influence than the one crafted by writer/artist Frank Miller in 1986’s The Dark Knight Returns. The flashback sequence is mostly silent and specifically focuses on the moment when the Waynes were brutally gunned down. Over the course of three pages, Miller chooses to take the exact opposite tack of the original Detective Comics speed-through — each panel takes place only nanoseconds after the previous one. He draws the eye to three core images that Bruce is implied to have fixated on for decades since: the gun, the bullet, his mother’s pearls.

By decompressing and breaking down into iconography the moment when the character’s life irrevocably changed, Miller brought a fresh spin that has influenced Batman writers, artists, and filmmakers ever since. As such, we included a page from the sequence in our roundup of 100 pages that shaped comic books. I asked Miller to talk about creating it and was pleasantly surprised to find out that he was inspired by another page on our list.

“What I was mainly after was to make it as intimate and as from young Bruce’s point of view as possible,” Miller said. In doing so, he turned to the work of the great Bernard Krigstein, an artist who experimented with depictions of time during his tenure at EC Comics. “The particular artist I studied to influence it was Bernard Krigstein, the EC artist in the ’50s, who would break what we’d do in a single panel into four or five panels,” Miller said. “So I wanted to echo that so the memory in Bruce Wayne’s head was so vivid that he felt it as if the ten seconds of his parents’ murder went on for hours.”

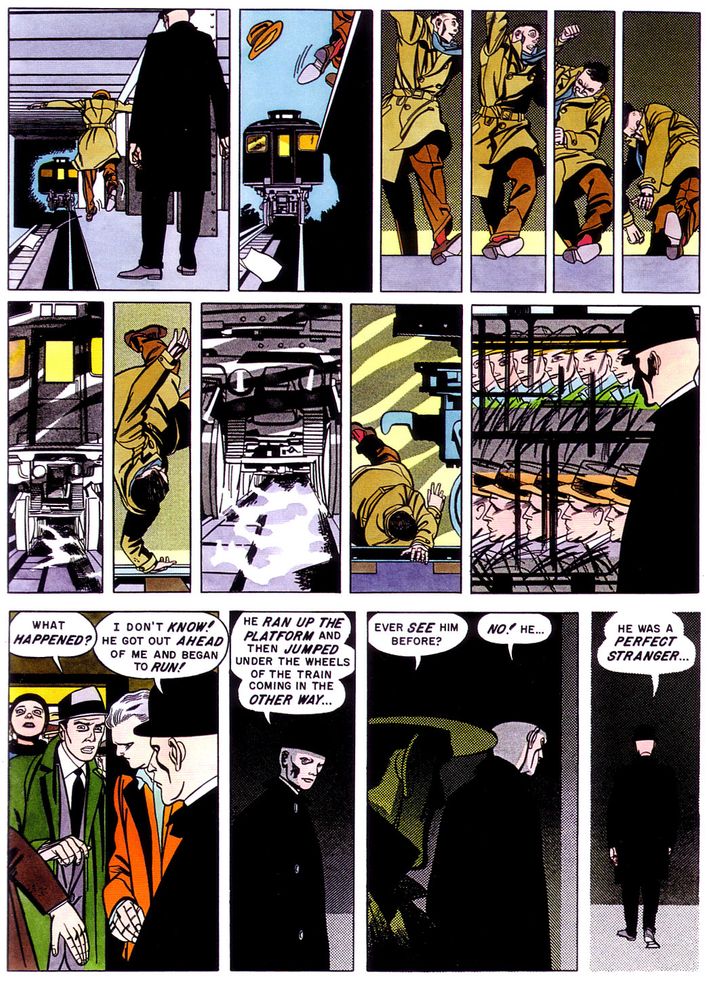

Krigstein’s best-known work is a short story published in 1955’s Impact No. 1 called “Master Race,” written by Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein. It’s a chilling eight-page tale in which a paranoid German immigrant to the United States named Carl Reissman takes the subway and recalls escaping from a Nazi concentration camp. Gradually, we learn that he was no virtuous escapee — he was the camp’s commander. While on the train, by happenstance, he sees one of his former prisoners, who had sworn vengeance on Reissman in the final days of the war. Terrified, Reissman runs from him and trips onto the tracks, where he’s killed by an oncoming train.

The story was groundbreaking for its frank discussion of the Holocaust at a time when such things were still too raw to regularly talk about, but what has given it immortality was Krigstein’s composition. A conventional page would likely have shown a panel of Reissman tripping, then a panel of him on the tracks. However, Krigstein opted to break the fall down into nine panels, giving the page a kind of strobe-light effect that makes Reissman’s demise all the more vivid. This was revolutionary at the time, and left an impression on Miller when he read a reprint of it, having been born two years after the comic was initially published.

When I pointed out that one can see parallels between the climax of “Master Race” and the Bruce Wayne origin sequence, Miller cut us off. “Oh, it’s not a parallel,” he said with a little chuckle. “He came first and I imitated him.”

To be fair, Krigstein wasn’t his only inspiration for the three-page retelling of the murder. I asked him whether he went back to previous versions of the origin story; “Oh, yeah,” was his reply. He said he looked back at the work of legendary 1970s Batman artist Neal Adams — “You couldn’t really draw Batman without being influenced by Neal Adams,” as he put it. But more important were Batman stories by artists Jerry Robinson and Dick Sprang, who worked on the character in the 1940s and ’50s. “Their visions of the character and the storytelling were really powerful,” he said.

One thing he couldn’t figure out: how he came up with the idea to focus on Martha Wayne’s pearl necklace. I asked him whether he lifted that from someone else’s depiction of the murder and he replied, “I don’t know! I don’t know. I’d love to claim it as my own, but everything comes from somewhere. I don’t happen to recall what that must’ve come from.” I pointed out that the pearls have since become iconic in other renditions of the death and he was reluctant to toot his own horn. As he put it, “Everybody gets to contribute something. And what’s good tends to stay. It’s a collective work, all together.”

Ultimately, Miller approached the discussion of the page with modesty and gratitude to what had come before, as well as respect for what had come since. I asked him for final thoughts on his recounting of young Bruce’s tragedy, and his reply was blunt: “Keep it simple. It’s perfect the way it is. Best origin in comics.”