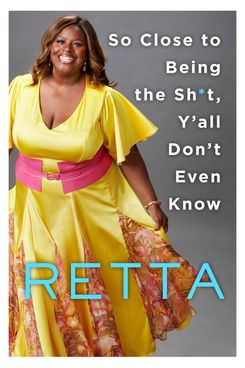

The following essay is an excerpt from comedian and Good Girls star Retta’s new memoir, So Close to Being the Sh*t, Y’all Don’t Even Know, out May 29.

One day in the fall of 2005, I was sitting on my couch, eating Cabaret crackers and watching TV, when I got a call from my manager.

“This is big,” he said.

Mmm-hmm. I wasn’t falling for that old line. Last time I heard that, I was sent to audition for a part on a kid’s show … with no lines. How do you audition for a part with no lines? Exactly.

“Are you sitting down?”

I was sitting down. I’m always sitting down. I’d just bought a used DVD set of The Shield and was deep into the corruption of the LAPD Rampart Division. I was on about my 435th episode watching Michael Chiklis, aka The Commish, perpetrate some helluh shady shit. Yo, that show was deep. Rill deep. So, yeah, I was sitting.

“This is really big.”

Alright. Spit it out already.

“We got you an audition for Dreamgirls,” he said, then paused for maximum dramatic effect. “The lead.”

Record scratch. What?

The Tony-award-winning Broadway musical was being turned into a mainstream movie, and I was being called in to audition for the iconic role of Effie White, the talented but temperamental singer fired from the Dreamettes, an all-girl group that was a thinly veiled version of Motown’s The Supremes.

The star-studded cast would be:

Beyoncé. (Shut up.)

Jamie Foxx. (For real?)

Eddie Murphy. (Getttt the fuck outta here!)

And Retta?

Yes, Retta. Why not Retta? This was the call I’d been waiting for my whole life; it was the opportunity of a lifetime. I was so incredibly grateful and proud, and yet the biggest feeling I had wasn’t excitement. It was dread. And I am telling you, I did not want to go.

Which was insane because I’d always considered myself a pretty fearless person when it came to performing, ever since I’d belted out “Chim Chim Cher-ee” from Mary Poppins in a second-grade assembly. I blew the roof off the James Madison Primary School gym in Edison, New Jersey. I hadn’t stopped singing since, everything from a high school production of Anything Goes to my karaoke go-to, “Killing Me Softly” by The Fugees. The genre that falls directly into my sweet spot is classical. I’ve been known to kill some Vivaldi, still, I was pretty sure, with a little practice, I could sing Dreamgirls’ most famous showstopper, “And I Am Telling You, I’m Not Going” with the best of them.

But could I hold my own as an actor with the likes of Jamie Foxx and Eddie Murphy and Beyoncé? Firstly, Bey wasn’t Queen Bey just yet. She wasn’t even Bey yet, really. At the time she was Beyoncé, the lead from Destiny’s Child who had just gone solo and had appeared in The Pink Panther and Austin Powers in Goldmember, neither of which were “dramatic” benchmarks by any stretch of the imagination. This was way before she broke me with Lemonade. She’s evolved and been through some shit so imagine her performance now! So, no, I wasn’t scared to share the screen with the pre-queen.

And, although Eddie is a living legend, the last thing that stuck in my mind about him was the transsexual hooker he got pulled over with.

It was prominent in my mind because it happened very near my studio apartment and all I could think was this is where Eddie hangs out? I don’t hang out around here. And hey, if that’s your jam, then that’s your jam. Whatever. But there have to be better pickup locales.

After that, Eddie was pretty low-key. Killing it in the voiceover field as Donkey in Shrek, but again, he wasn’t doing drama.

Jamie Foxx, however, had had a huge hit in Collateral with Tom Cruise and then knocked us all out with his Oscar-winning role in Ray. So, yeah, that may have given me pause, but you know what? That’s what the hell I was here for. I came to LA to do my best among the best.

So, no, I wasn’t intimidated … per se. I’d been a legit working actor for almost ten years, starting at the bottom and working my way up. I got my start in entertainment doing stand-up at a sorority charity event when I was a junior at Duke University. I had absolutely no idea what I was doing. I just got up there and winged it, regurgitating funny stories my younger brother had told me about him and his friends. My set killed and my inner attention whore wasn’t mad at that crowd approval. For the next four years, I worked as a contract chemist during the day (I’ll tell you about that later) and at night did open mics at Goodnight’s Comedy Club (also known as Charlie Goodnight’s) in Raleigh, North Carolina, one of the top comedy clubs in the United States. I had one goal in mind. I wanted my own sitcom — The Retta Show.

In 1997, I packed my leased car and moved to LA, armed with a stack of unfortunate head shots and a book titled Your Film Acting Career. I auditioned for anything I could, and fine-tuned my stand-up.

Your girl husssssstled and that shit paid off. I won Comedy Central’s stand-up competition in ’99 (which later came to be known as the Laugh Riots competition) and was awarded a brand-new Mercury Cougar, a year’s supply of Taco Bell, a spot on Comedy Central’s Premium Blend and, most importantly, it led to a spot on the New Faces showcase at the 2000 Montreal Just for Laughs festival. The New Faces showcase was a huge deal because all the television development execs in Hollywood go to see the talent. For a relative Hollywood newbie these credits, along with a costar appearance in Moesha, appearances in two films, and an HBO pilot, weren’t shabby.

Moesha is one of three all-black projects I’ve ever booked … in my career … to this day, and I think that partially fed into my fear about the Dreamgirls audition. This was an iconic piece of black theater. I call it black theater because even though it wasn’t written by black authors it was mostly an African American cast depicting R&B acts of the 1960s and ’70s. And as my manager kept pointing out, it was going to be Big. At the time, I felt like I didn’t really fit into the black comedy scene. I told myself I wasn’t urban enough in my act. I just wasn’t covering the same subject matter that I saw other black comics doing. I didn’t write about growing up in the projects, smoking weed, or my epic sexcapades — not that I had any. That wasn’t my shit and, as a result, I feared the black audience for a long time.

I remember doing a set at the Phat Tuesdays show at The Improv and I was scared to death because I didn’t know if I’d be embraced by a black crowd. I was one of those girls who the black girls in my high school said sounded “white.” Everybody knows you can live or die on a black comedy stage. I didn’t think they would like me, because I wasn’t doing quintessentially black material. It took me a long time to learn that as long as you’re yourself that audience will accept you. You transcend it. There are white comics who do black shows and kill. As long as you’re yourself, and you’re funny … you’re good. Dreamgirls being a “black” classic could serve as my vehicle into the hearts of the black audience. It seemed the safest bet because I wouldn’t be playing myself, I’d be playing a character. A beloved character. An iconic character in the black theater canon. Giving me the chance to finally be recognized by the black audience.

My original goal was to be a sitcom star. Now I was being offered an opportunity to be a movie star? Yeah, a movie star. But first I’d have to get through the audition. I’d have to prove I was the perfect Effie to a roomful of producers, casting agents, and the director, Bill Condon — who just happened to be the Academy Award–nominated writer of the film adaptation of Chicago. I’d have to sing “And I Am Telling You, I’m Not Going.” Probably a capella. For them to hear. With their ears. Now if that doesn’t make you want to shit your pants, I don’t know what will. I practiced in the shower 100 times 100 different ways, but that couldn’t prepare me for the real deal. As many times as I had auditioned in my career, I still felt sick every time. This would be infinitely worse. Why? Because this was going to be Big. That motherfucker was in my head.

The fear of rejection is real, my friends. When you’ve had your fair share of soul-crushing, self-esteem-destroying experiences, it’ll do a serious number on your psyche. Here’s one for the record books: A famous female TV writer-producer, who had created a beloved all-female sitcom in the ’80s, was all about me after I auditioned for her new pilot. She decided I wasn’t right for that part but wanted to create something for me. Every six months, she’d check in with me and ask if I was available. Um, yes, I’m available! I’m never not available for you! She’d come up with a show idea for HBO about an all-female vice squad in downtown LA and was I interested? After I immediately said yes, she told me the character was a lesbian.

“She’s hardcore. I think you’d be great.”

Okay, just give me a job! That’s what I wanted to say. But before I could, I panicked. This was cable. HBO. Lots of nekkidness.

“I gotta say, I haven’t done a lot of things on camera, so I’ve never had a sex scene on camera. I’ve never even kissed a man on camera so I definitely haven’t been skin on skin with a woman. I can’t show my tits and I can’t lick anyone else’s. I think I can handle kissing a woman but that’s about it.”

“Oh, you’d never have to do all that!”

She was right because the vice thing didn’t see the light of day. Instead, she decided she wanted to do a dramedy about a wealthy Texas family and called me up again with the pitch, which was also being developed for HBO. “Their housekeeper who lived with them forever had a daughter and they loved her so much, they sent her to college and law school and now she’s the attorney for the family. That’s your part!”

“Word? Okay.”

“She’s a lesbian. And her name is Retta.”

“You really tryna make me a lesbian, huh? I’m down. Let’s do this.”

I had already shot a pilot for HBO called $5.15/Hour. The suits at HBO were nervous. Sex and the City was ending and they were looking for another hit. They had high hopes for two promising projects: $5.15/Hour and another pilot called Entourage. “Entourage doesn’t look that great,” the execs on $5.15/Hour snickered. “It’ll never go.” I’ll give you one guess as to which made it to air and which didn’t.

Even though my show didn’t go, the suits knew me, liked me, and had said as much, so when this producer pitched me as the lesbian family lawyer I knew I was in like Flynn. Or so I thought. It turned out I was gonna have to audition for the part. The part she’d created just for me. The character she naaaaamed Retta. Apparently, one of the casting directors had her doubts about me and needed to see me read. I agreed to go in, but now I was helluh nervous. After that first audition the writer-producer called me to tell me they wanted the director to meet with me. We would talk about the part and I would come back to do another producer’s session.

After that second audition, the producer called me. “I can’t believe I have to make this call …” she started but didn’t need to finish.

I didn’t get the part. It was the most heartbreaking rejection I’d had since I’d arrived in Hollywood. Tossed back into the ocean of actors, like a rotting boot on a fishing line, I kept checking IMDb to see if they kept the character’s name as “Retta.” I was prepared to die a thousand deaths if they had but thankfully they did end up changing the name. Plus, it never aired.

I’d like to say this was the acting Gods lookin’ out for a bitch, but sadly, this kind of thing happens all the time. I had a friend named Wendy get fired from her own show named Wendy and someone else was hired to play Wendy. Let that shit roll around in your cerebellum for a second. Fucking brutal.

Even a full year after the rejection, it’s hard not to give up when nightmares like that happen. You’re bitter, broken, and usually broke.

But just when you’re about to throw in the towel, something like Dreamgirls rolls in. Every time you try to get out, they pull you back in! A week had passed since my manager first gave me the great news that the Dreamgirls producers wanted to see me, but I still hadn’t set up a time for an audition.

“We really want you to go in for this!” he begged again.

All I could say was, “That’s crazy.”

This was my big chance and I was blowing it. Was I in shock? What was happening? What was wrong with me?

I could sing, I could act, but even more than the fear of rejection and judgment from the black audience, there were two things crucial to a lead role, like Effie White, in a period musical still holding me back and giving me massive anxiety. For one, I couldn’t dance. Back up, back up. I can dance. I love to dance and I know I gots moves cuz when I used to break shit down at parties folks would be like dammmmmmn. I don’t know if it was because they were surprised that a big girl could dance, but people were always impressed with my skeelz. When I used to go to clubs in college I didn’t need somebody to ask me to dance. I was there to work, to work that floor. We did all the dances, the Monster Wop, the Butterfly, the Tootsie Roll, the Cabbage Patch, the Biz. I would do the Reebok but would incorporate the pause and the robot turn from left to right. Whaaaaaaat?

Every year for my birthday party, I hire a DJ and there are two separate rooms. The bar room and the dance floor. I make sure everyone knows the dance floor is for dancing. “Don’t come in here if you’re not gonna dance. Don’t waste the space. Do not come up in here unless you’re ready to bring it.” I believe that 75 percent of dancing is facial expression and that’s another reason why I think I appeared so good at it. Very few people can compete with my facial skills. I’m not a professional dancer, I don’t have any formal dance training, but I did tap and dance numbers in high school productions.

I was a quick study when it came to choreography.

So, in conclusion, I can dance. I’m just not physically able to do choreography anymore. I have two knee injuries from junior high and college, and a messed-up ankle from an accident at a Hollywood party. Right after I got to LA, I went to a shindig at a house in the Hills. I didn’t want to go, I was in a stank mood, but my friend insisted. The place was packed. I poured myself a drink and about forty seconds after I stepped out onto the deck, the deck collapsed. I dropped about five feet and dozens of people fell on top of me. I was on the bottom of the pile with a dislocated ankle. After everybody stopped screaming and finally got up, a kid who looked like he was rushing Kappa Sigs stood over me.

“It looks like your ankle’s dislocated. We need to reduce your ankle!” he screamed frantically. “I can do it! I’m a med student at UCLA!” His halitosis was sponsored by Maker’s Mark and I wasn’t about to be his practice dummy.

“We don’t need to do shit. And I’m gonna need you to back the fuck away from me.”

The fire department finally came and a few handsome fellas saved me. They strapped me to a long backboard and carried me out of the yard like a swollen Cleopatra. The night left me with a pair of ruined jeans, an outrageous hospital bill, and a fucked-up ankle for the rest of my life. How was I gonna dance in Dreamgirls with a wonky ankle and a pair of busted knees? I pictured myself asking the director for too many breaks and asking a resentful production assistant for too many ice packs, thus ending up the set “diva” who had all of four credits to her name. I didn’t want to get a reputation as a pain in the ass.

Second, the idea of wardrobe was freaking me out. I knew all those girls in The Dreamettes would have to dress alike and I was scared they wouldn’t be able to find matching dresses in my size. I was so green to the filmmaking scene that I didn’t know the costume department would just make us all the same dress. My neophyte ass thought they were going to Nordstrom to shop for a period piece. I was also panicked that I’d have to wear heels. I don’t wear heels. I can’t. I have to wear completely flat shoes at all times because of the pain and scar tissue in my ankle.

I was clueless and I’d created this whole story in my head of how it was gonna go down. I convinced myself I couldn’t survive the shoot, a shoot I hadn’t yet been asked to join. A film I hadn’t even auditioned for yet.

I was sure I couldn’t do it.

So I didn’t do it.

I never said no; I was way more chickenshit than that. I just kept avoiding it, putting it off. For about three months I never made myself available, and it got to the point where they had a movie to cast and so they did. They went with the seventh-place finalist of season three of American Idol. They cast Jennifer Hudson. She had no credits. But you know what she did have? The balls to show up to the audition.

When it was official that I wouldn’t be auditioning because the role was cast, I wasn’t relieved. I was ashamed of myself. For the first time in my life, I understood the phrase “the fear of success.” Before then I always thought it was the dumbest thing I’d ever heard. But now I got it. Because that was what I wanted. To be in those big movies with big stars. That’s why I was here. But I was scared. Scared of things not going perfectly. Scared of being perceived as a problem. Scared of sharing the screen with big names. Basically scared of success.

The next Christmas, I went to see Dreamgirls with my brother back home in New Jersey. He didn’t know that I’d been offered an audition for Effie. I didn’t tell anyone. When the lights went down, and I saw Jennifer Hudson on the big screen for the first time as Effie, I looked down at her feet.

She was wearing flats. The kind you can fold and put in your purse.

Mother. Fucker.

I have no doubt, I could have sung “And I Am Telling You, I’m Not Going.” I don’t know that I’d have sung it better than Jennifer. She won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress based on that performance. What I do know, if I can get Franklin D. Roosey here, is that I let the fear of fear itself get the best of me. Jennifer hadn’t done jack before that movie but she had the confidence within herself to take a risk that paid off big-time.

I did not win an Oscar but I learned a valuable lesson that stays with me to this day and plays on a loop in my head anytime I have a big audition. It goes a little something like this:

Bitch, stop wasting time fearing the worst. Living through the worst is never as hard as fearing it.

Fight the fear and go do what you gotta do. That’s what you came here for.

From So Close to Being the Sh*t, Y’all Don’t Even Know by Retta. Copyright © 2018 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.