“At this weak, pale, tabescent moment in the history of American literature, we need a battalion, a brigade, of Zolas to head out into this wild, bizarre, unpredictable, Hog-stomping, Baroque country of ours and reclaim it as literary property.”

That’s a line from the late Tom Wolfe’s “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast,” a 1989 Harper’s essay urging American literature to move away from the then-fashionable model of “realistic fiction” (defined by Wolfe as writing about “real situations, but very tiny ones, tiny domestic ones, for the most part, usually in lonely Rustic Septic Tank Rural settings”), and toward something more like Charles Dickens, Honoré de Balzac, Émile Zola, and Theodore Dreiser — and, well, more like The Bonfire of the Vanities, Wolfe’s 1987 quasi-Dickensian potboiler. It takes a special kind of audacity to write an essay exhorting people to write like you.

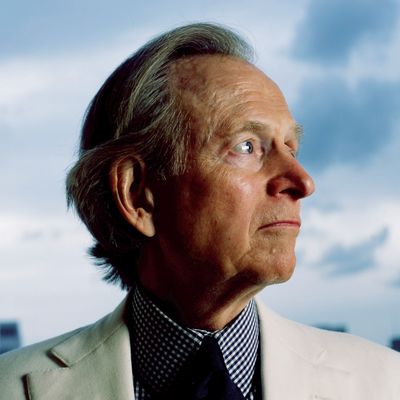

But that was Tom Wolfe. The wry southern dandy in the bespoke white suits had an ego as big as the world, and the serene conceit that he exuded was justified, up to a point. Wolfe was not just one of the pioneers of so-called New Journalism, which applied techniques of fiction to reportage; he was its most famous practitioner, rivaled only by Hunter S. Thompson, whose own star rose a bit later. During the first third of his career, Wolfe was a relentless chronicler of class, status, and cultural relativity in the United States, going on safari to document subcultures that seemed exotic to the kinds of readers who subscribed to the outlets that published Wolfe. Although he was no pup when his career started to catch fire — his breakthrough piece “There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy-Kolored (Thphhhhhh!) Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (Rahghhh!) Around the Bend (Brummmmmmmmmmmmmmm)…” was published in 1963, when he was in his early 30s — Wolfe made his reputation explaining the young to the old and the cool to the square.

But time caught up with him eventually. When you look back over the full arc of his career, you see the times outpacing him, and you hear his once inimitable, fresh voice doing pirouettes and backflips to camouflage the fact that he wasn’t organically plugged into the culture anymore. He was another elderly white man, albeit one more curious and open-minded than most, trying to pin down a fast-changing and increasingly unrecognizable world.

Time has a way of making fuddy-duddies of every writer. It’s humbling, in its way. His Bonfire period looks, in retrospect, like the crest of his importance, the culmination of nearly 30 years spent honing his voice and philosophy. The book was such a smash that the next few years of Wolfe’s life revolved around promoting and defending it. It summed up a particular style of American obliviousness, a substratum of Reagan-era reactionary greedball thuggery that was swallowing the American mind. It made Wolfe a true household name, a brand, really, and not even the box-office failure of the film version could tarnish his aura as the all-knowing interpreter of the Zeitgeist. In Robert Altman’s 1991 Hollywood satire The Player, the hero, studio executive Griffin Mill, is dispatched to read the latest Tom Wolfe book (invented for the film) in galley form; sight unseen, his boss tells him to bid $1 million. Bonfire was the big one, the book that Wolfe had been building toward.

He waited until he was in his 50s to publish his first novel, but he’d been experimenting with non-newspaper-approved techniques during the quarter-century leading to that point, glitzing up journalism with a linguistic fireworks display that included such previously forbidden devices as onomatopoeia (Ka-BLONGGGGG!!!!), excessive em dashes — you know, like this — and this — gosh, here’s another one — and ellipses … and exclamation points (!), even multiple exclamation points (!!!!!!), and CAPITALIZED WORDS deployed for EMPHASIS or for IRONIC EFFECT, and dramatic … pauses, and all manner of hemming and hawing and, you know, come on, like this, see? It all gave readers the feeling that Wolfe was standing right in front of you, a man in a cream-colored suit tripping over his own fabulous vocabulary as he tried to find the words, the right words, exactly the RIGHT ones, to explain how amazingly incredibly EXCITED he was about the people and places he’d just seen. According to the introduction of Wolfe’s first essay book, 1965’s The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, the titular piece, the first to be written in the now-recognizably Wolfean style, got printed in Esquire because Wolfe was blocked on deadline and sent his editor, Byron Dobell, several pages of unfiltered notes. Dobell stripped “Dear Byron” off the top and published it. The piece was about the custom car and motorcycle culture; the subsequent, similarly titled essay book also included profiles of record producer Phil Spector (“The First Tycoon of Teen”), disc jockey and impresario Murray the K (“The Fifth Beatle”), and “The Last American Hero Is Junior Johnson. Yes!”, an elegiac look at stock-car racer Junior Johnson that was eventually adapted into a Jeff Bridges movie.

Thus was Wolfe’s brand established: He was the cultural spelunker, donning a snappy fedora instead of a pith helmet and venturing forth to report on the bold, the cool, the authentic. The 1968 nonfiction book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, which followed Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters around, was one of the first widely consumed accounts of the American counterculture, released mere days after the debut of Hair. Radical Chic and Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers (1970) reprinted two lengthy New York articles about, respectively, a party thrown by Leonard Bernstein to benefit the Black Panther Party, and the ineffectiveness of social programs being administered by white bureaucrats to San Francisco’s poor black, Latinx, Chinese, Native American, and Samoan populations. (Reread the latter and you’ll see harbingers of the tin-eared take on race relations that would problematize much of Wolfe’s later writing —though it’s buried so deep within Wolfe’s still-lacerating portrait of performative white guilt that it’s not the first thing that jumps out at you.)

Wolfe was fascinated by what writers of earlier decades might’ve called “the manly virtues” — stoicism, single-minded focus, no-fuss competence, devotion to “a code”; the Steve McQueen and John Wayne mythos — and by the time he published what is arguably his masterpiece, 1979’s The Right Stuff, a lean, rollicking nonfiction book about the Mercury astronauts and the test pilots who preceded them, it was clear that even as he tried to poke holes in macho façades, he couldn’t help being impressed by how near-impervious they were. Philip Kaufman’s 1983 film adaptation of The Right Stuff exhibits some of the same glamorizing tendencies, though it does an equally good job of satirizing the public-relations aspects of the space race, the self-promoting inclinations of NASA and the White House, and the credulous stenographers of the press. (Of all Wolfe’s fellow practitioners of New Journalism, only Norman Mailer did a better job of evoking the bland American hive-mind that took hold during NASA press conferences.) The phrase “The Right Stuff” was itself an indication of Wolfe’s genius for identifying an elusive something and making it nearly concrete: It was, among other things, “the ability to go up in a hurtling piece of machinery and put his hide on the line and then have the moxie, the reflexes, the experience, the coolness, to pull it back at the last yawning moment — and then go up again.”

Wolfe was a master at hanging labels on mind-sets and qualities that seemed indescribable, or that had not yet been captured in print by another writer because nobody else had his particular eye. “Social X-Ray” described the emaciated, plastic-surgery-sculpted society women that populate the upper echelons of the world’s cities. “Mau-Mauing” deployed as a verb, described how nonwhites used race-based intimidation to shake loose public funds from stingy white government agencies. “Radical Chic” was the fashionable public display of social conscience by rich (usually white) people who harbored socially liberal attitudes. “The Me Decade” described the post-counterculture focus on the self that defined the 1970s: Wolfe coined it in 1976, in the pages of New York. Wolfe is even credited with the phrase “Good Ol’ Boy,” which appears in his profile of Junior Johnson — a phrase that was originally used in England, where it had a different meaning, but that perfectly described the mental fraternity that linked socially conservative southern white men of every social class.

Wolfe’s mojo dimmed, as tends to happen to writers who keep applying the same tried-and-true creative methods that worked for them in the past, even when the future is staring them in the face. His 1998 novel A Man in Full was a southern-fried Bonfire gloss in which a white woman’s rape accusation against a black athlete sets Atlanta on the path toward racial violence; however exhaustive Wolfe’s reporting was, reading the finished book was a tiring and off-putting experience, filled with descriptions of youth culture and black culture (and black youth culture) that felt stranded somewhere between National Geographic and Fox News Channel. The book’s hero, a thick-necked good ol’ boy businessman named Charlie Croker, eventually emerged as the unquestioned hero of the story, at times verging on a folksy redo of one of Ayn Rand’s virile, two-fisted industrialists, facing down lily-livered, mealy-mouthed hordes of hand-wringing liberals and boisterous, accusatory minorities.

Bonfire exhibits a bit of that same sensibility, that of an unreconstructed southern white guy loosed upon the scary multicultural metropolis. He seems to understand and even empathize with the moneyed bond trader Sherman, his girlfriend Maria, the Assistant District Attorney Larry Kramer, and the world-weary judge Myron Kovitsky, all of whom are white, but the novel’s major black characters, including accident victim Henry Lamb’s mother, are treated as ridiculous caricatures or downtrodden emblems of society’s indifference, and whenever the book spends time in black neighborhoods, you can feel Wolfe’s heart racing along with his characters’. His penultimate novel, 2004’s I Am Charlotte Simmons, was similarly irksome. The concept deserved points for audacity — Wolfe, 72 at the time of publication, was writing about the contemporary sexual mores of college students — but much of it came across as simultaneously leering and censorious. Reviewing the book for New York, Cristina Nehring called Wolfe’s view of youthful eroticism “dark” and “rotten.” “For all his incisive, inclusive observation, for all the student jargon he has mastered, he is nearly the age of his old nemesis, Norman Mailer,” she wrote. “And with age comes disbelief; with age comes a kind of pessimism. The capacity for wonder is the elixir of youth.”

Charlie Croker might have been Wolfe’s own fantasy of himself, a Sherman McCoy with muscles and a sense of honor, somebody who could stand fast in changing times even though the world swirling around him became more unfathomable by the week. Still, throughout his career, Wolfe had a knack for insights that seemed to sum up entire mind-sets and experiences: “The problem with fiction is that it has to be plausible. That’s not true with nonfiction.” “A cult is a religion with no political power.” “Art is a creed, not a craft.” “One belongs to New York instantly, one belongs to it as much in five minutes as in five years.” “The reason a writer writes a book is to forget a book and the reason a reader reads one is to remember it.” Wolfe forgot a staggering amount of great writing, and the best of it is ageless.