Adapted from the forthcoming Henry Taylor: The Only Portrait I Ever Painted of My Momma Was Stolen, to be published by Rizzoli Electa with Blum & Poe.

He began to realize he had some sort of mystic powers. He felt he was able to touch people, to contact certain souls in the next room or miles away or even those who had died. —Charles Mingus, Beneath the Underdog: His World As Composed by Mingus

When I became interested, forty years ago, in Negro art and I made what they refer to as the Negro Period in my painting, it was because at that time, I was against what was called beauty in the museums. At that time, for most people a Negro mask was an ethnographic object. When I went for the first time, at Derain’s urging, to the Trocadéro museum, the smell of dampness and rot there stuck in my throat. It depressed me so much I wanted to get out fast, but I stayed and studied. Men had made those masks and other objects for a sacred purpose, a magic purpose, as a kind of mediation between themselves and the unknown hostile forces that surrounded them, in order to overcome their fear and horror by giving it a form and an image. At that moment I realized that this was what painting was all about. Painting isn’t an aesthetic operation; it’s a form of magic designed to be a mediator between this strange, hostile world and us, a way of seizing the power by giving form to our terrors as well as our desires. When I came to that realization, I knew I had found my way. —Pablo Picasso, c. 1946

I.

Henry Taylor was leaning on his long, low, white kitchen sink in his large but sparsely furnished house in the West Adams neighborhood of Los Angeles as he tried to tell me his ever-evolving theory about how he had found his way into the paint, and the pain. The day before in his car, somewhere between Malibu and Calabasas, Taylor had told me about his search. The time he had spent wandering the halls of his community college in Oxnard, trying to figure out how everything he saw, all that he took in, was going to make its way out of his insides and enter the world.

It wasn’t until the mid-1990s, years that coincide with the last time that Los Angeles festered in rage and riots, that Henry Taylor decided to devote himself full time to painting, and when I asked him why those years had felt urgent to him, he had a provocation to try out as an answer.

“Man, it was important … Sometimes we think we have moved on and then suddenly we go back. Maybe the riots were that moment? And in that way, maybe that is my ‘Black Paintings’ moment?”

He was referring to the series of 14 paintings that Goya secretly made on the walls of his home, having been overcome by the fear that he was going insane. They are an explosion of grief, watchfulness, and despair. A man once known for his courtly portraits had found himself alone and almost deaf, and in his panic, the Spanish painter created private paintings considered to be both an epic showing of a master’s late style and an illustration of his virulent depths. In his “Black Paintings,” Goya captured Spain’s political turmoil and his disappointment with humankind. They were a reckoning with his time and his place and a display of one man’s most mortal concerns.

“The riots? Tskkkk! They were a black period, or a blue period, because it was the beginning,” he exclaimed. During those years, Taylor’s most mortal concerns were honesty, history, and memory. And there in his kitchen, where he was wiping down the counter, then throwing away pieces of too-ripe fruit from an overflowing bowl and in between it all stopping to occasionally pour small thimbles of Jack Daniel’s into his glass, Henry Taylor was trying to explain how a city, especially the city of Los Angeles, had a way of constantly radicalizing itself, and how it could wake a person up, agitate art, expression, and rebellion. But really he was telling me something metaphysical — he was telling me how this particular place and that exact time woke him up.

“Because sometimes, for whatever reason, that subject, it doesn’t go away. Blackness doesn’t go away! There’s some things that just never go away. And who knows why? With the riots, you experience something and it just alters you, how you look at things. Because you know nothing is ever gonna be the same.”

“Lately,” he said, then stopped all of his motion abruptly, and, full of reflection, he stood very still until he continued, “I sometimes start to think about that. Because I was just painting something in my studio, and I was thinking about how it was real dark, and I said, ‘I got the “blue period.” ’ I was thinking about the ‘blue period,’ because of the colors that I was using, but also because I was telling myself, Picasso don’t know what a ‘blue period’ is. Because the blues, you know what I mean, the real ‘blue period’ is here. You know?”

Henry Taylor’s house is a painter’s house — a house that has more paintings than chairs. In his living room, arranged around a giant garlanded Christmas tree, are one life-size stuffed hyena and an ebony grand piano. In another room are portions of Taylor’s art collection: a sculpture he had made that resembles a confederation of African spears, a Bob Thompson painting, and a Noah Davis painting. I had known Davis long ago, when we had both been wild first-year college students in Brooklyn. And Taylor bonded with the young black painter after they had both been featured in the Rubell Family’s “30 Americans” exhibition in 2008, when Davis was just 25.

Throughout Taylor’s house that day, Kendrick Lamar blasted on the stereo, and paintings that he had signed for Shawn Carter (a.k.a. Jay Z) lay on the second floor. On the stove, in a cast-iron pot, pork chops in gravy were stewing. Someone was coming to pick up the paintings for the rapper, who was very keen to have them mounted that week so they’d be in his house for Christmas. While we waited for his gallery’s courier to arrive, we took in the warm, bright Angeleno December morning by sitting outside in Taylor’s garden and eating the pork chops with white rice and drinking green juices his gallerist brought over. There Taylor told me about everything he had devoted himself to before studying painting: linguistics, cultural anthropology, journalism.

He told me he had also studied interior design, but that I had better not tell anyone because it was a secret. Why is that secret, I asked. And with his eyes bulging, Taylor flashed me a look of disbelief. “Because it’s embarrassing! Interior design? But hey, man, I was just looking to express myself somehow and some way. In any kinda way? You understand? You know what I’m saying? You know what I mean?”

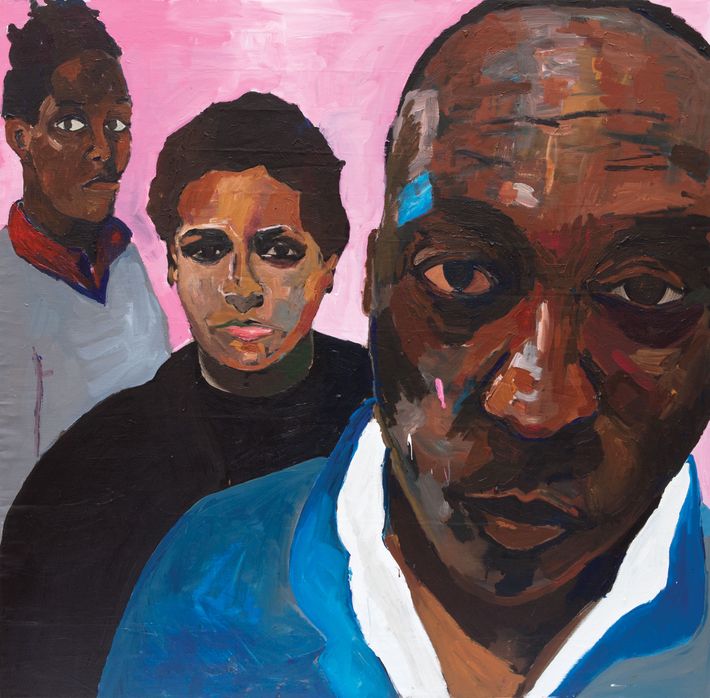

You know what I’m saying? Taylor will say this over and over whenever he talks, knowing full well that the chances are you probably don’t. But sometimes, to “get” Henry Taylor, you just have to return to the paintings. Because it is all there, a chronicle of his compassion and love for California splayed out on the canvas, his testaments to the heft and the marvel of modern black life in 20th-century America. A chronicle that seems to draw upon many sources — his obsession with the uneasy moments, the many faces, around him, and the deceptive, flirting beauty of someone who never thought that they would ever sit for a painted portrait for the first time seeing their face reflected back to them in the paint.

What only a few people will ever tell you is that portraiture done well is a retrieval of the sitter’s soul. “The soul has to stay where it is,” wrote John Ashbery in his poem “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror.” “Longing to be free, outside, but it must stay / Posing in this place. It must move / As little as possible. This is what the portrait says.” When Henry Taylor paints, it is as though he had been born with caul over his eyes, as if it were nothing for him to access that low-down, murky place where we store who we are, the part we’d often most like to conceal from others. Because of this, all of Taylor’s paintings merge into a great, unending sweep of people whose eyes, large and inescapable, articulate the same chorus. I was here. Even if it was or wasn’t always easy to be here.

II.

There is something unguarded about Henry Taylor. He reminds me of people I used to know. His way of being is all earnest. It is all homegrown. It is all real. For him, blackness is not an uneasy, overcompensating assertion, it isn’t the who’s-hot-and-who’s-not social jockeying of the art world, and it is completely bereft of any performative anger. Gone is all of the Talented Tenth’s navel-gazing over double consciousness. Blackness for Henry Taylor just is, much like whiteness for Fairfield Porter just is.

The work comes from where his eye falls. It comes from the people he knows and the people who have passed away. In his garage on the day that I visit is an eight-foot-tall portrait of a brother in a stocking cap flexing a bicep. His eyes menace and track the yard. “That’s the man who killed my cousin,” Taylor tells me. “I saw that picture of him online. I think he was just let out of prison, so he started posting pictures of himself. When I saw that one, I knew I had to paint it.” In Taylor’s office is another huge canvas, painted with a tableau from rural East Texas that shows the woman who raised his mother. “I’d never seen my mother weep like this before. We went to visit, and when this woman, Cousin Tip, stepped out on her porch, my mother fell down in that dirt and the tears just poured out of her.” On the floor is a self-portrait and its twin, a painting of a white woman with her legs crossed, smirking and holding a cigarette. A painting of his mother watches over the kitchen table. Over a stretch of sea blue and above a white stove, Taylor has painted the word cornbread and circled the letters “C, O, R, A,” Taylor’s mother’s first name. “That’s my mother,” he tells me blithely, and I take it in as if I were making the woman’s acquaintance in the flesh.

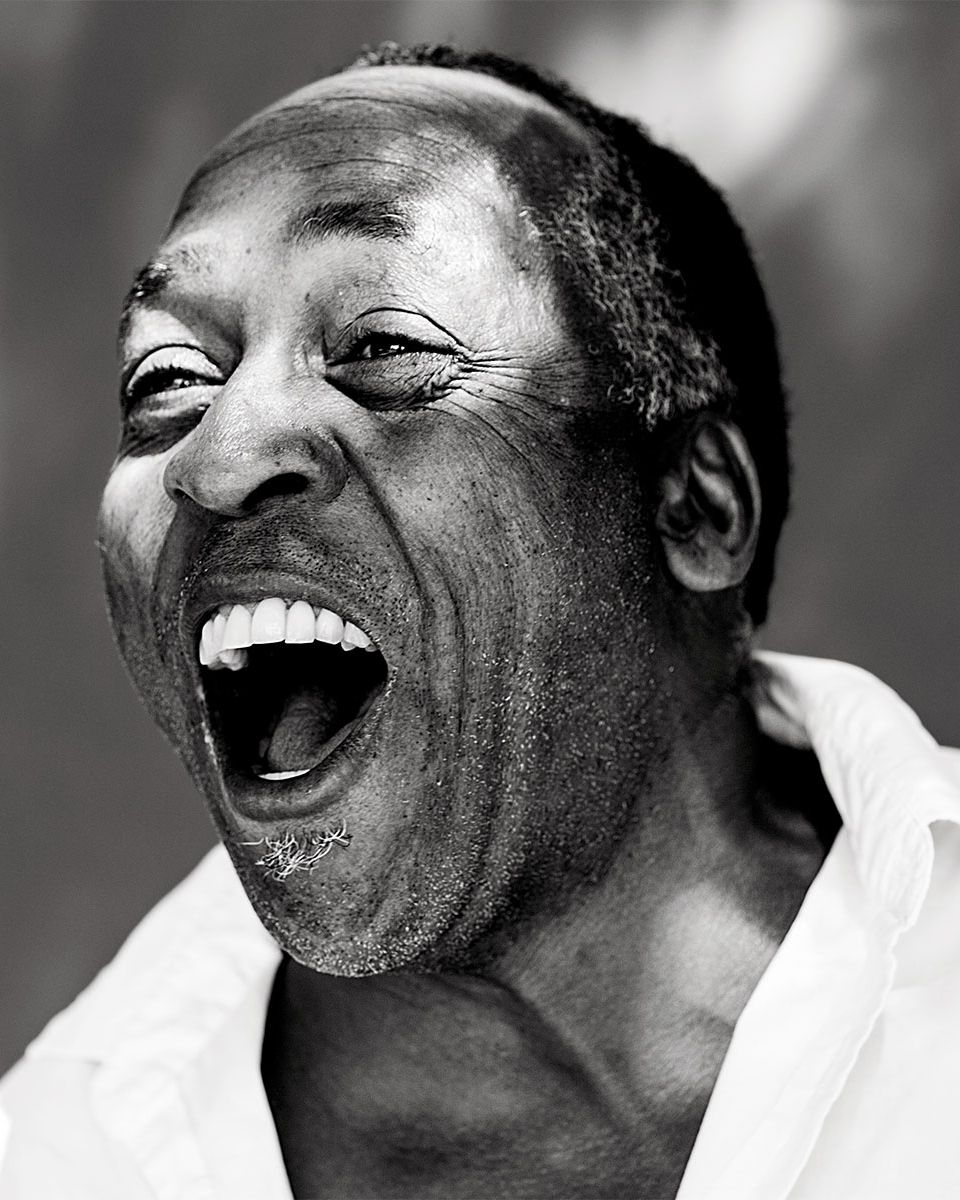

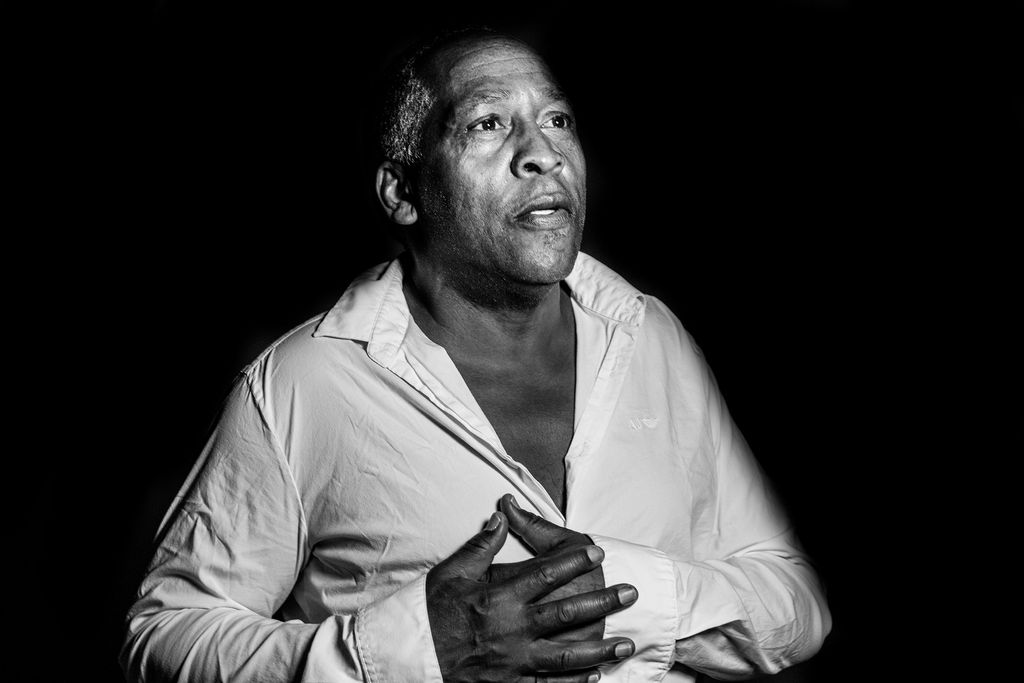

Last year, Taylor’s gallerist, Timothy Blum, said in an interview around the opening of the Whitney Biennial that featured Henry Taylor the painter that Henry Taylor the man is “like a walking, living, breathing work of art, and alongside being a visual artist, he’s a poet. He sort of embodies that wherever he goes.” The word that Taylor uses for this never-ending observation is gather. “I’m gathering faces.” At other times, he says he is cataloguing. He is cataloguing the passages of time. He started taking in these details as a child. The clothes and rituals of the strangers who passed his window on their way to church in their Sunday best. The way his brothers’ legs bent as they jumped over the anonymity of being just another Negro into local stardom as hurdlers and high-school track stars. The mysticism in the way he felt certain, after an accidental but lengthy backstage conversation with Bob Marley, that he would never see the wise man ever again. He was right; Marley died soon after. There is the story of his brother Earl, the Vietnam veteran who wore cuff links and dressed sharp every day and came home alive but died years later from the shrapnel that was still buried within him. There are his mother’s cousins. The silhouettes of the horses that his grandfather traded and sold back in Texas because he refused to be reduced to picking cotton.

And the present occurs here too: The homeless men who still come to his door looking to bum a smoke. The way his friend Hamza Walker, the curator, sits and glances down to read a pile of art books. The foreboding but handsome face of a young woman in Cuba who reminded him of his niece. The diabetics with their amputated feet wheeling themselves across the freeway. Taylor tells me that he likes Matisse, mostly because he tries to learn from the French old master how to get away with not giving a sitter a foot or a blurry hand — repurposing the wild style of Fauvism.

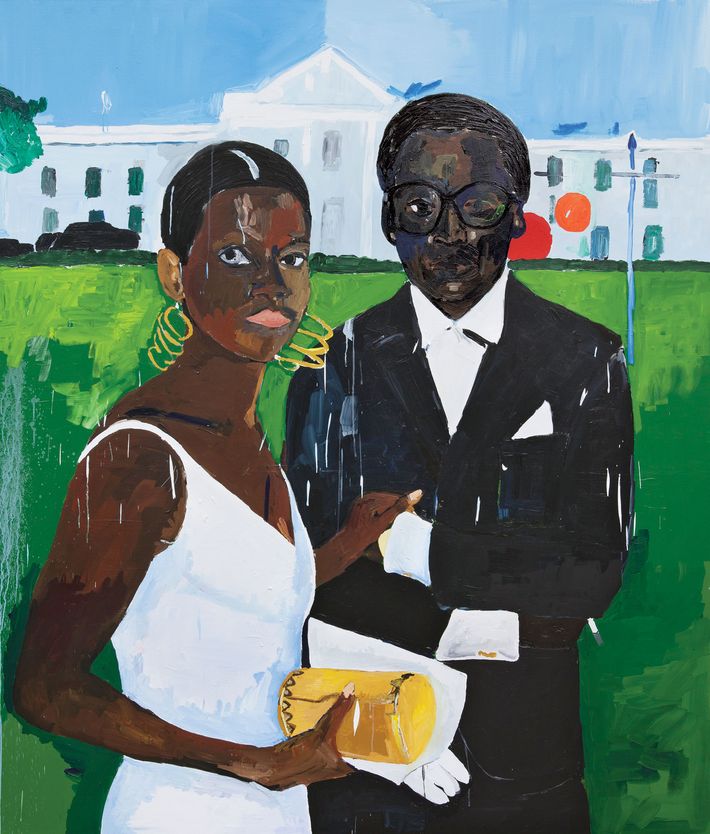

But this feels like a way to conceal the depths of his admiration, since I detect in his pictures of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department buses carrying black people as if we were chattel toward the city’s correctional facilities that Taylor knows what it means to paint The Sorrows of the King. How else do you account for his painting of Philando Castile, the one with a lament for a title? The suspended agony of the school aide sitting in his car, taking that bullet to the chest, and dying with his eyes open to the crime of his death. “Sometimes we cry when we don’t want to cry,” Taylor once said in an interview with designer Duro Olowu. “It’s a sensitivity, and sometimes … there are things I’ll never forget.”

When I arrived one morning at his house, I found Taylor outside in his yard; spread out in front of him was an article titled “The Uncounted.” The print wasn’t that large, but I noticed that Taylor unconsciously placed his coffee and his ashtray away from the title so it remained intact and unblemished. Sometimes, for Taylor, the headlines become the work.

But what I realized then was that the work is also a way of making sense of the headlines; it is not only his catalogue of the people he cannot forget, but also his assemblage of the people he wants to see more clearly — the uncounted. “I didn’t used to ‘see’ my brother,” he explained. “The one who was burned, and then one day he told me, he said, ‘You know, Henry, I always used to wear T-shirts when I ran track because I was burned. I didn’t want to wear a jersey.’ You know how ballplayers used to have those wifebeater-type — for lack of a better word — shirts. He never wore one, but I never thought about that, and I said, ‘Man, my brother had to go through so much.’ So sometimes you almost have to … it’s almost like being a writer, Rachel. You try to get inside of that person.”

Taylor’s portraits are sincere but brash. Bright but muted. They wink at you but can feel weighed down with a mood that is grim. Their lines are both vague and specific, but what unites them all is his treatment of the subject. With every face he paints, there is a sense that Taylor is moving to capture the ineffable, to strip away both the mask and the persona, to retrieve the way someone is wonderful with their lip twisted jauntily just so before the moment is over and whatever secret truth he saw in their face that made it worthy of capturing has vanished.

“I paint fast and slow. It’s like a game. It’s like a basketball game. You can paint a fast game, and sometimes you’ve got to just slow it up. But I think that energy is felt. In some ways, I think it comes to me. It definitely comes through me.” When Taylor says things like this, I’ll always think he is talking past us and repeating that boast to himself — even though he paints as if he were staring the world down, as though he were in the ring or on the court. I think he does this because this is how you roundhouse the ephemeral. You repeat “I’m fast” to yourself over and over, until it is something real, a face emerging from the wet thickness of your paint.

III.

Who set you free to be the person that they could not be? To understand why Henry Taylor cares about tempo, speed, and the physicality of painting, you have to understand that Henry Taylor is the eighth child of a man who liked to call his sons his “bullets.” A man who loved his children and provided for them, but whose love is best remembered by an incident in which he broke up a domino game and threatened to kick the ass of a man named Carl for telling Henry to stop showing off his new car and turn his damn music down. Henry Taylor’s father was a proud man who wanted to raise proud, tough children.

All black people are the expansion of someone else’s dream. We are the knock on the door that demands to be let in and no longer deferred. Taylor’s parents were both from Texas. His mother was a domestic worker, and she cleaned houses, something that used to bother him until he got old enough to go and help her. Since he was the youngest, he was allowed a rare amount of access to her. There was a private language, a continent of maternal flesh, that only they shared. He would wash her back, and she would touch her scars and bruises, wounds of a tough childhood in Texas. With her own mother in an asylum, she had grown up as an orphan with murky parentage, and as she bathed, she would recount how she had received them. “My mother would say, ‘Come here.’ And I,” Taylor remembered, “would wash her back off, and then she’d be sitting in the bathtub and she’d show me her knees and say, ‘Look at this, baby. This is from when I was a little girl. They used to make me do this.’ They didn’t let her go to school. They stopped her from going to school because it was just after the Depression and they said, ‘You know what, you’re going to pick cotton.’ ” Which is how she survived until they left for California.

Henry’s father was a painter on the Point Mugu naval base in Ventura County. When his father was a boy in Naples, Texas, just 9 years old, he witnessed his own father being shot multiple times and left with just enough life in him to stagger back to his mother’s porch, arms flapping loose what life they had in them, his feet doing all they could to carry him home, whereupon, reaching the porch he yelled that they needed to patch him back up so he could return to the fight.

Later on, when he was ambushed once again and shot dead, his young son helped his Big Momma drag his daddy’s dead body back inside.

Taylor’s father was a man who demonstrated little tenderness. Having seen all of that, you best believe that there was a certain pragmatic, survivalist logic to why his own sons had to be his biological bullets. They were this black man’s way of saying, “Warning shot not required.” On the weekends, his father brought out boxing gloves, and in front of their house, the Taylor boys boxed one another senseless until they got good. Until they got tough. Very, very tough.

Other times, his father took him out to tag along on his painting jobs on Saturday mornings. It would seem obvious that this early education in using paint (albeit industrial- and commercial-strength paint) and paintbrushes was the firmament for Taylor’s work and his work ethic. Henry Taylor never stops working. He not only paints black labor, black labor practices (jazz gods like Miles Davis, feats of black athleticism like Alice Coachman acing the high jump), and black laborers, he works like a laborer too. From afar, his practice has come to appear antic, but when you look up close, it’s clear that Taylor has a traditionalist’s belief in habit, consistency, and keeping the hours of a man with a day job. He works like someone who has paid his bills by throwing paint on walls for more than 40 years. But what was an industrial skill for the father has become a creative act for the son.

When I remark to Taylor that although they painted different things, doesn’t it mean something that he and his father both painted? Doesn’t it matter that his paternal grandfather in Texas was alleged to have been such a strong draftsman that he was able to supplement his income by counterfeiting? So isn’t Henry, then, just the passage of time, the arrival of options that can finally intersect with the talent? Instead of answering me, Taylor started to weep. “Only recently have I started to think about that.”

The last time he spoke to his father, his father had wished Taylor well and expressed his pride that he was graduating from CalArts. The call had surprised Taylor. He was surprised that his father even knew that he was graduating. Because he had never expected his father to understand what painting meant to him.

It was his sister, Anna Laura, who, after going to his first show and seeing what her brother had been up to, seemed to best understand where the inner lives of their people and their parents’ stories had landed. Anna Laura was the one who called Randy, their older brother, and told him, “You gotta come here. Randy, Randy. You gotta come see Henry. Randy, Henry can paint. And Randy, Henry’s paintings will scare you to death.”

IV.

The house on Hill Street, the one that Henry Taylor grew up in, is painted white. He grew up in a white house. In the back hovers a small apartment complex that was owned by his cousin. It is difficult but not impossible to see how eight children could have been reared in this humble house. It is not impossible because, if anything, the small white house on Hill Street is similar to other small houses scattered all over America. These are houses that black people relocated to when they, like Taylor’s parents, moved away from Naples, Texas. Or like my grandfather did, from Alexandria, Louisiana, to California. From Opelika, Alabama, to Oakland. Or elsewhere. When Taylor showed me his home, what is remarkable is that it looks like the Jacksons’ home in Gary, the Williams sisters’ home in Compton, and Diana Ross’s home in Detroit. These homes have eaves that hang low with the burden of migrants’ hopes; their designs are simple, to give credence to the wishful thinking that with success, the architecture will improve; they are meant to stand as a marker of the passage from what was into what will be. It is no wonder that so many of these homes are the humble incubators of black artistry.

Taylor was born in 1958. At the crossroads of what America was and what it was attempting to become. Next door to the Taylor family lived an elderly white woman and, on the other side, a Chicano family who treated the Taylors as if they were relatives. When Taylor drove me to meet one of his oldest friends, I was surprised when the door was opened by a tall, gregarious white man named Vincent.

By the seventh grade, Taylor was sitting courtside with his English teacher, Teresa Escareno, preferring to talk art with her than basketball with her husband, who was the gym teacher and coach. She introduced him to the terms Impressionism, Cubism, modernism, and all of the major artists.

In person, Taylor is the type of man who will bring up the work of the Hernandez brothers, the Latino graphic artists from his hometown, frequently, as if he wanted to remind you that equally influential for him, maybe even more so than any dead man from Europe, is their work, which seemed to teach Taylor a two-pronged lesson: that with just a pencil and paper you could make art, and that the art you made could alter someone’s sense of themselves by showing them what they are. “After seeing their drawings, I said, If I’m going to be an artist, I’m going to have to do a lot of fucking drawing.”

From there, a peripatetic journey: etching classes at small colleges, jobs cleaning up the studio of a Scientologist, and a week of work in a gallery owned by a woman named Ruth Schaffner, who collected African art. Later, there was the instruction of James Jarvaise, the Oxnard College–based painting professor whose work was featured in the 1959 MoMA exhibition “Sixteen Americans” alongside that of Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, and Jasper Johns and who, preferring his small classroom to fame, was the person who insisted in 1990 that Taylor attend school at CalArts.

Without much of a plan, Taylor invited me to drive out to Oxnard one afternoon. I’ll never know what to make of the fact that Henry Taylor called no one to let them know he was coming. We just went, past the cliffs of the Palisades, the length of Tarzana, the low-lying beaches of Malibu, and the suburban sprawl of Thousand Oaks, where Taylor once lived, until we reached the hills of Camarillo.

For ten years, Taylor was a psychiatric nurse at California’s largest state hospital. He was the man who made sure hundreds of mentally ill people who had all but been forgotten took their medicine, ate their meals, and got whatever care was deemed necessary. While working there, Taylor began to sketch the faces of his patients on thin paper. They were some of his first sitters.

There is a sea and a beach in Oxnard, supposedly, but I never saw it. The light was fading by the time we arrived. And after pointing out the rail tracks, the fruit orchards, and the “black neighborhood,” Taylor pointed to houses and said the names of the people who used to be there, who might still be there, or who are gone and he was just rendering them present because he was thinking about the past. Then he mumbled something about going to see his cousin, his aunt, who seemed to be one and the same, or many different people, but his explanation was confusing. When we arrived at a small beige ranch house, Taylor parked the car. We were greeted by two women. They were taking care of two other women. They are his extended family. They ribbed him and henpecked him. They teased him and shook their heads at him. Their pride was palpable.

Taylor is the youngest of his siblings. The oldest living person in his family is 101. Her name is Zephyr. In Zephyr’s room, surrounding her hospital bed, we stood there. Adjacent to the bed was a poster of Obama. Her grandchildren made her a banner to celebrate her birthday, and prayers are framed. In another room, an aunt who had a stroke but had a smile as serene as the sky and the prettiest manicured nails told us stories. “You don’t know how happy I am to see you, Henry,” she cooed. And the father of two, the worldly painter, was transformed into a boy. His cousin, a strikingly attractive, slender woman who lives in D.C. but was home to help out, chided him for eating chips and told him that she took the tour of his show at the Whitney.

“I kept saying, ‘That’s my cousin! That’s my cousin.’ But Henry, you got one thing wrong: Aunt Cora wasn’t that light.”

The room erupted into laughter.

Taylor blushed and conceded that she was right.

When the women sent us off, they said good-bye with those easy good-byes that make it feel as if a long time hasn’t passed and that no more long times will pass. “Okay, now, I’ll see you soon now. I’ll come to that next show. You tell me when.” They sent him off with warnings: “Watch out for yourself. Make sure you trust the right people. Be careful, you hear? Really, I mean it now.” As if this journey of his as an artist is no different, no less treacherous, than the one their family made two generations ago from East Texas.

Taylor thinks about them, his people, often, and in Oxnard, his fears about the limitations of his body and how much time he has left to capture them pervaded our conversation. These deep emotions can often come on like a penumbral shadow and overwhelm him. They are the burdens that come with being the keeper of the flame.

As we pulled away from his aunt’s house, there was the sense of evaporation, with what is left behind being mostly the memories he tries to capture. “I can paint portraits easy. What keeps me up at night is trying to really paint this.”

V.

One night in Paris over copper tubs full of Bollinger Champagne, Henry Taylor smoked a cigarette and was crowded by a group of Frenchmen and one tall brunette dressed in pale, billowy silk. I was there to catch the good, pink light of Paris and to get a break from my family in London. And Henry Taylor was there because his paintings were in the FIAC art fair, his work was being “introduced to the European market,” and he had rented a place in the Marais for a few weeks. Our meeting up was a happy encounter that had been arranged by Carol Cohen, Taylor’s former gallerist whom he trusts with his life. Among the smash of French socialites and club kids, European art advisers, and American art people, Taylor and I were two of the few black people. Which is something I noticed, even though it seemed like he did not. Henry Taylor is used to being the exception.

As with Bill Traylor, Clementine Hunter, and Jacob Lawrence, all too often Henry Taylor’s work is categorized under the outdated term “outsider art.” Without most people bothering to ask: Who is the insider and who is an outsider? And why?

In many ways, beneath the dinners and international exhibitions, the 21st-century art world often operates like an ideological Triangle Shirtwaist Factory — a deeply exploitative space, where its greatest minds are less valuable than the work that they produce. Typically, artists can expect to split the profits from the sale of their work in half with their gallerist.

This model means that efforts of an individual are sold in 50-50 split with someone who had little to do with the creative act but will earn as much as the person who did. The art world is a tremendously smug storehouse of worth, one where the people who make the art rarely set the prices.

The answers to the aesthetic element of these questions are implicit in Henry Taylor’s portraits. They all detourn and reevaluate worth. All portraiture is an act of one’s taking on the work of the mirror. The brush can act as a finger. Tracing the curve and capturing the flesh. The long-breasted homegirl is made into an odalisque. The slim slope and sway of his Mozambiquan muse’s body. The private grin and long patience of the Ghanaian woman he found in Accra who had sat for a portrait in 90-degree heat. A woman with milky-tea-colored skin washing her long arms in the tub. All of the sensuousness and exaltation of Gauguin can be found in Taylor’s nudes, but gone is the sense of invasion — in Taylor’s work, the man feels present in the act, as if this woman’s beauty isn’t outside of him but instead emblematic of him. Here, women who used to sit in the shadows, holding a fan, in an Ingres painting of a woman once deemed more worthy, are now placed in the center and put at ease in Taylor’s work as the ones who are beautiful. This is a radical decision. And it is no wonder that some people are made so uncomfortable by it that they have to place it outside of the canon.

Whenever you leave the States, being a black American in many places will add a quiet but certain allure. Black people are, to adapt Adrian Piper’s theory, the mystery of the object. And that night in Paris was no different. The tall woman asked to take our picture. She wanted to remember the night. I declined.

“You all are so beautiful,” said the tall woman. It was sincere. Her thrall for everyone in the banquette was absolute and sincere.

She asked us our names.

She introduced herself. She is the star of the Paris ballet. Which I translated to mean: I am a star. Aussi étoile, I said, pointing to Taylor. Painter. Stars lit up in her eyes.

He didn’t notice this either.

“This is crazy,” I yelled to Henry Taylor over the crowd.

He grinned and nodded.

“This is crazy. Look at how much they treat us differently over here,” I continued.

I knew from having a West African father that if we were Algerian, Senegalese, or even a black European, it would be different. But tonight, we were black Americans in Paris.

In the club that night, the warm, low lights made Taylor’s eyes look red and wet. He lurched back, widened them, shook his head in agreement and disbelief.

“Aye, aye, man, right? Man, listen, you’d get used to this, couldn’t you?” he said, taking a quick drag and then exhaling a long stream of smoke straight out for what seemed like at least a definite minute. And then he shook his head, rubbed his chest, and chuckled. Knowing that this sense of things wouldn’t last and that what felt good was the moment. So, for the moment, we enjoyed it.

It took me a long time to make sense of what Henry Taylor and I encountered in Paris that night. Months later, at the Yale Center for British Art, I would stand looking at portraits by Hans Holbein, Peter Paul Rubens, and William Hogarth and understand for the first time the historical significance and commentary found in portraiture. In these paintings, the artists placed not just satire, value systems, symbols of wealth, homages to their nations’ peace and prosperity: They were also demarcating what made them great. The work was not an objective rendering of what the painters saw but rather a record of what they wanted us to see. What Taylor and I felt that night in Paris was that we were being seen as something worth adoring — a bit fetishistic perhaps, but it felt closer to our sense of self than the callousness and revulsion that we can experience from others when we are back home. Where we must do all of the seeing by ourselves for ourselves.

VI.

Before I ever met Henry Taylor, I saw Henry Taylor. There he was, sitting cross-legged, cool, in Noah Davis’s hospital room at Cedars-Sinai, pointing his hand into the air.

I’d known Noah in Brooklyn, back when we were just kids. When I remember him now, I see him bending over his father’s long dining-room table in Brooklyn, absorbed in a book about Balthus. I’d never seen that kind of concentration before. It was as if just he and the book existed in the world. Noah was a Cooper Union kid. I was at the New School, and I think that although there was a certainty about what we wanted to be — if not who we had to be — if we wanted to like ourselves, there is also something dervishlike and crazed that occurs whenever a black kid decides that he or she is going to make art.

Like most people living now, we found each other again on social media. I watched Noah get sicker through images. Sometimes I wrote to him in his message box; other times I commented. When Noah posted, Henry Taylor or Henry Taylor’s work often appeared in his feed. “Yeah, Henry,” Noah wrote. Noah posted one Taylor painting that I still think about. A black boy pissing in a white man’s mouth. Yeah, Henry.

I’m not sure why I refused to think that a man who was so young — he had just turned 30 — could ever leave this Earth. Noah had the sight. He had the gift. How could someone like that leave? He couldn’t. Life was invariable, but it was not dumb. It wouldn’t so stupidly ravage away what made it wonderful. Confident that he would be fine, I wrote Noah a note to encourage him to keep fighting.

He wrote back, and signed the note: Oh, those Brooklyn Days, things were so easy then.

A few weeks after this, Noah was gone.

There are people younger than you who become your teachers. I never had any doubt in my mind that Noah was one of my teachers. I do not think that my mind will ever flash like his did, or that my smile will disarm like his could, but I know that Noah made me mindful of the fact that the world needs wild-hearted people, people who seem to be made of pure fuel and who find energy from the agony and uneasiness of life. In doing so, they find a way to create and leave something behind that links them to what was and what will forever be.

When I saw that picture of Henry Taylor sitting in Noah’s hospital room, sketching him as he lived out his last days, I felt a relief that rounded out the other feelings. Their bond abated the fear because I knew from the moment I looked at Henry Taylor and then saw his work that Noah had done something monumental. He had found that someone he had always been searching for. He had found a fellow traveler, a maverick, another brother who saw red, a painter who also felt the spirit; he had found a beholder, a teacher, and a friend. He had found another artist who was true. One who was wild with love. And I think — no, I know — that we had always been looking for someone like Henry Taylor, and neither of us had ever encountered anyone like him during those years in New York.

Whenever I look at Taylor’s paintings, in the solace of seeing a single sitter staring back at me boldly, not blinking, I also see a palimpsest of stories that I can step into, because Taylor knows how to remind us that we are not at all alone. In one painting, underneath the image that we recognize, we can see the many. His father, his mother, his brothers, his sisters, his neighbors, and his nightmares. Here is our young friend Noah, who didn’t make it over, smoking a cigarette wearing a suit jacket and shorts. These are his complex remembrances of the black folks who wandered westward like the lost Hebrews in Exodus. Here are the contours of a people who were not only desirous of finding their promised land but who were also hoping to re-create and reconstruct themselves as being glorious. This cultural movement into the city was our way of declaring one’s self free. The Great Migration was a chance to pack the blues, the beloveds, and the bad loads into a knapsack and declare that instead of being burdened with the past, we would own it. People who are badass and tricky now, like Hermes — a god carrying a few messages, some good, some bad, but still a god. What Henry Taylor is painting is that moment, and not only the many private griefs that make us weep and recall the wells that our grandparents got their water from, but also the release of those things and our movement ever onward.

*A version of this article appears in the June 25, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!