Set in the 1970s, George Pelecanos’s 1997 novel King Suckerman takes its title from a fictional movie the novel’s assorted hustlers, psychos, and accidental criminals spend much of the story intending to watch. When the title comes up in conversation, the characters’ reflexive response becomes a running gag: “The one about the pimp?” But when some of them finally get around to seeing it, they get more than they bargained for. It begins like a typical blaxploitation film of the era, one in which “the injustice of Ghetto Life specifically and Amerika in general had turned a basically good brother toward a life of crime,” only to allow him to escape it after having his revenge in the final reel. But then the movie goes its own way, showing the brutality exacted by its titular pimp then sending him to jail, where he’s destined to die. “From the beginning,” Pelecanos writes, “the audience sensed that there was something unsettling going on.” When it concludes, one character declares it “boolshit” but his more experienced companion corrects him. “That there was the real deal.”

Classic blaxploitation films are often a combination of creative bullshit and the real deal — sometimes within the same frame. The films thrived in the early ’70s, and their low budgets sometimes led to no-nonsense location shooting that offered a documentary-like look at the turbulence and neglect of inner city life in that era. And their plots usually diagnosed the sources of those problems correctly, from racism to drugs to a corrupt system with no interest in letting those on the bottom get ahead. They also featured larger-than-life heroes who — using flair, firepower, brawling skills, and some well-timed quips — could overcome these obstacles. Most times, the movies sent mixed signals, condemning the brutality of street life while celebrating those who knew how to bend it to their will. Or as Eddie, right hand of protagonist Youngblood Priest puts it in the 1972 film Super Fly, “I know it’s a rotten game, but it’s the only one The Man left us to play.”

Directed by Gordon Parks Jr., Super Fly provides some of the best examples of the way the tension between those mixed messages could make the genre feel so vital, largely thanks to Curtis Mayfield’s soundtrack, which often seems to be suggesting the darker, more honest movie that Super Fly won’t quite let itself be. Carrying on the tradition of tying the story of a dealer trying to get out to a strong musical voice, Director X’s 2018 remake, Superfly, features a soundtrack produced by Future, who appears on the lion’s share of its tracks. Future’s an apt choice for that Atlanta-set remake and his soundtrack is well worth a listen, but the pairing doesn’t lead to the same fractious, compelling marriage of music and images as the 1972 original.

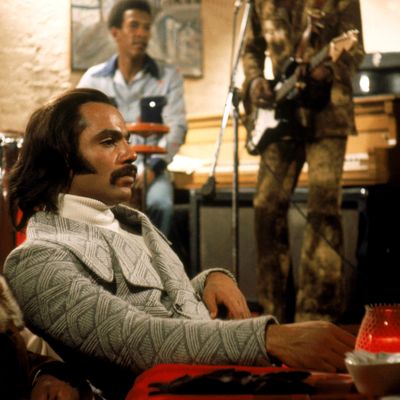

Then again, few such pairings do, as the 1972 Super Fly’s opening moments make clear. Mayfield composed the songs for the film working from a script, but he brought one preexisting track with him, “Little Child Runnin’ Wild,” which plays over the opening scene of two junkies walking the streets of a down-on-its-luck Harlem. Their goal, we’ll soon learn, is to rob Priest (played with theatrical intensity by Ron O’Neal). The song continues over our first glimpse of Priest, looking glum as he snorts coke and reclines in a post-coital languor next to one of his two girlfriends. And there, in some respects, is the whole movie: Here, you can be desperate and scrounging or you can be on top. But Mayfield’s plaintive falsetto and the song’s dramatic strings speak of another truth: Misery will find you either way. “Didn’t have to be here,” Mayfield sings in the voice of a nameless kid growing up in this world. But really the opposite is true. Nobody here has any other choice.

Mayfield was already well known for his socially conscious music, first with the Impressions and later as a solo artist. But for as often as he made inspiring songs, he didn’t look away from the darkness. His solo debut, Curtis, opens with nearly eight minutes of apocalyptic imagery thanks to “(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Down Below, We’re All Going to Go” (which currently serves as the theme song to the HBO series The Deuce, co-created by Pelecanos). Here, his songs sometimes seem to be providing a thematic counterpoint to the film. The soundtrack’s first single, “Freddie’s Dead,” became a hit before the film’s release. It’s a lament for Fat Freddie (Charles McGregor), an amiable low-level dealer killed on the job. In the film, Freddie’s death has a narrative purpose but it doesn’t really touch any of the characters. In Mayfield’s hands, it’s a tragedy worthy of commemoration and Freddie a worthy stand-in for all those cut down “pushin’ dope for The Man.” Parks repeatedly returns to an instrumental passage from the song and it’s almost as if Freddie is haunting a movie that otherwise seems to have forgotten him.

The songs set the tone in other ways at other points in the movie. Parks was the son of Gordon Parks Sr., who’d directed the blaxploitation hit Shaft the prior year, after already enjoying a successful career as a photographer, most famously for Life magazine. His son was a photographer as well — though he used the name “Gordon Rogers” early in his career to avoid the appearance of benefiting from his famous father’s reputation — and midway through the film he uses still photographs to trace the spread of cocaine to all corners of New York, from uptown to the docks. It’s a daring choice that could have played as accusatory or celebratory or just goofy with the wrong choice of music. Instead, Mayfield’s funky “Pusherman” makes the presentation seem matter-of-fact as it circles back to one line from the chorus: “I’m your Pusherman.” Whatever else he is, Priest is a man doing his job in a city of many occupations.

The film was a controversial in its time, earning a condemnation from the Hollywood head of the NAACP for glorifying the drug trade. But its depiction is more nuanced than the finger-pointing suggests, and much of the credit belongs to Mayfield, whose soundtrack has had an afterlife of its own, and whose view of Priest is even more complicated than the film’s. It’s easy to get lost in the groove of the title track, making it possible to miss lines like this: “Ask him his dream / What does it mean? / He wouldn’t know.”

The new Superfly doesn’t attempt quite as complex a fusion, though Director X — a music-video veteran who uses the film to work that aesthetic on a grand scale — makes memorable use of songs from Future’s soundtrack in a few moments. It fills the luxurious strip club of an early scene, a place where bills and butts fly through the air with abandon. Miguel’s slow jam “R.A.N.” scores a soft-porny three-way lovemaking session. But some of the film’s most dramatic moments are set to Josh Atchley’s more conventional score, and as good as Future’s tracks sound, there’s nothing here that suggests they had to be tied to this take on Superfly. In a telling touch, both “Pusherman” and the original film’s title track swell during key moments, almost as if this new version doesn’t dare try topping them.

This might be because of changing attitudes toward soundtracks. Mike Nichols collaboration with Simon and Garfunkel on The Graduate started a trend of musicians working closely with directors that was still going strong in 1972. Blaxploitation produced some of the best pairings, like Isaac Hayes’s Shaft score and Marvin Gaye’s Trouble Man. (Even failed team-ups had a way of working out. Larry Cohen rejected James Brown’s songs for Hell Up in Harlem, but that didn’t stop “The Payback” from becoming one of Brown’s biggest hits.)

That tradition has mostly fallen away in the decades since in favor of soundtrack albums featuring a broad range of contributors. It’s been showing signs of coming back in a slightly new form, however, thanks to curated releases like this and the Kendrick Lamar–orchestrated Black Panther soundtrack from earlier this year, a rich, thematically unified collection, albeit one made up heavily of songs not played in the film itself. Superfly could have taken that a step further, but for all the plot points reverently transported over from the original film, this new version doesn’t borrow its intimate connection to one artist’s music, or the ways it uses songs to say something beyond what its stylized, glamorized images of one clever player’s adventures in the world of dope can say. It’s a film whose heightened reality and alternate-universe version of Atlanta was never going to feel real. But the right songs could have made it feel like the real deal anyway.