It’s August, which can only mean one thing: Winona Ryder season is upon us. This month sees the 30th anniversary of Heathers’ initial theatrical run, and a confluence of Ryder-related happenings to commemorate it. She and Keanu Reeves have two tickets to paradise in the upcoming rom-com Destination Wedding; and in New York, two different repertory movie theaters have scheduled retrospectives of the celebrated actress’s work. The Quad Cinema’s “Utterly Winona” collects her most notable credits from the ’80s and ’90s, while Brooklyn’s Alamo Drafthouse invites moviegoers to “Winona Forever: A Winona Ryder Mystery Marathon,” in which four unannounced selections from her diverse filmography will play back-to-back. This month, Winona fans will be living in the best of all possible worlds.

Across her varied résumé, a quick mouth has been one of a small handful of constants, so how better to survey her career than by quotable moments? Vulture singled out 12 sound bites from films stretching through her auspicious beginnings to mainstream fame and onto her fascinating, unpredictable present. Read on, already! What’s your malfunction?

“My whole life is a darkroom. One big, dark room.” –Beetlejuice

Like most child actors, a young Winona Ryder began her career as a novelty act. U.S. audiences got their first real impression of the 17-year-old as Lydia Deetz, the pallid-skinned goth daughter of a family unwittingly putting down roots in a haunted house. A then-rising Tim Burton honed his kooky-macabre aesthetic just in time for Ryder and her persona of disaffection to fit snugly into it. The director plays the morose-little-girl bit for laughs, with Ryder putting a percussive punch on each syllable of “big dark room” to drive home the adolescent despair. With a lesser actor, it would’ve come off as precocious, a kid wearing world-weariness like a too-big suit. But Ryder sells the line, as if anyone who cared to look close enough would find that she’s not being completely tongue-in-cheek.

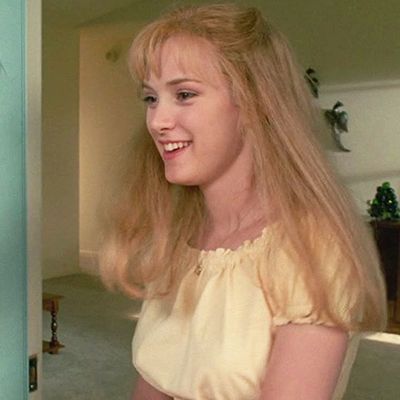

“You know what I want? Cool guys like you out of my life.” –Heathers

Production on the definitive Winona Ryder movie wrapped in 1988, the same year as Beetlejuice, though the Stateside theatrical release wouldn’t come until the following spring. Still, it feels as if a much wider gulf separates that performance from this one. Burton’s whimsical approach to the teen years was gently chainsaw-fucked to smithereens by the lacerating, pitch-black cynicism of Mark Waters’s script. Our gal Veronica cedes a lot of the most sublimely bitchy lines to the single-named trio of queen bees, but she delivers the closest thing the film gets to a mission statement when she finally dispatches charming sociopath/love interest J.D. (Christian Slater). Being “over it” was the guiding principle of the first phase of Ryder’s career, and her exasperation reaches its peak over the slick, manipulative hipsters that lusted after cool girls like her.

“I don’t know how to be a wife. I’m only thirteen.” –Great Balls of Fire!

Her parting words to J.D. presaged the gauntlet of public creepiness to which emerging actresses in their teen years are often subject. A carnivorous media was all too happy to oblige a public hoping to leer at the starlet, and though perhaps inadvertently, she transmuted that discomfort into her supporting performance for this Jerry Lee Lewis biopic. Dennis Quaid gave a serviceable showing as the godfather of rockabilly music, but as with Walk the Line, his spouse stole the show. Lewis fell head-over-soft-incestuous heels for the 13-year-old Myra Gale Brown, undeterred by the difference between their ages or her status as his first cousin’s daughter. She could not always reciprocate his affections. She states in plain language that the responsibilities of adulthood, be them sexual, romantic, or simply emotional, had been thrust on her before she was ready. The years to come would bear this out.

“Hold me.” –Edward Scissorhands

Burton’s next collaboration with Ryder makes for a natural point of comparison with their breakout film, and reveals just how much she had grown as a thespian in the course of two brief years. She plays the Fay Wray to Johnny Depp’s emo-dreamy Frankenstein’s monster, defending him from the townspeople too cruel or intolerant to see the gentle beauty beneath his frightful exterior. It could have been a thankless role, but Ryder manages to redefine the pointy-handed leading man on her character’s terms instead of the other way around. His love for sweet Kim Boggs illustrates that he’s got a beating heart like any one of us, and on the subtler flip side, Kim’s recognition of a kindred spirit in an alienated loner speaks to a deeper hurt at her core. She speaks an integral half of the script’s most tender exchange, lodging a naked request for intimacy and opening herself up in good faith that he wouldn’t do anything to hurt her. His meek answer of “I can’t” confronts her with one of adult life’s tougher truths: The ones we love most can hurt us without even trying.

“It’s like Popeye says: I yam what I yam!” –Night on Earth

Having built up some industry cachet with an acerbic string of high-profile credits, Ryder used her street cred to spend the early ’90s teaming with auteurist filmmakers who knew how to put her crackling wit to good use. First and quite possibly foremost was Jim Jarmusch, who tapped Ryder to go against type as Corky, a tomboy cabbie with big dreams of graduating to grease monkey. As she carts around a casting director played by a resplendent Gena Rowlands, the two exchange idle conversation that hints at the more profound depths contained within each of them. The scene’s punch line comes when Rowlands’s character offers Corky a role that could change her destiny, and she politely declines so she can continue to pursue the life of a mechanic. The bulging-bicep sailor man encapsulates her worldview with the catchphrase she offhandedly quotes; chasing fame or fortune isn’t quite as fulfilling as pursuing her more idiosyncratic interests. Same goes for Ryder, who’d show the world just how diverse her tastes were over the following decade.

“I want to be what you are, see what you see, love what you love.” –Bram Stoker’s Dracula

Everyone involved caught a lot of flak for Francis Ford Coppola’s overflowing, opulent take on the seminal novel about Transylvania’s most famous resident. Keanu Reeves got the brunt of it for sticking out like a sore surfer-dude thumb in Coppola’s heady classicist atmosphere, but as the apple of his eye, Ryder more smoothly integrated herself in the style and tone. Her Mina Murray is made of stern stuff, self-possessed and ripe with desire. When she finally gives herself over to Dracula’s seductive bite, she articulates her hungers in directly consumptive imagery; more than merely joining him in the afterlife, she wishes to fully subsume Dracula. The sentiment is fitting for a woman with feelings too unruly for her time, and for the sort of characters toward which Ryder has gravitated. Regardless of their era, they’re strong-willed, passionate, and too clever by half.

“You do love me, Newland. You’ve made me so happy.” –The Age of Innocence

The first half of the ’90s saw Ryder trying her hand in the world of period pieces, and discovering that she got along swimmingly with the petticoats-and-bodices set. After going late-19th century for Coppola, she fell back a couple decades to the 1870s for Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence adaptation, then slipped into antebellum times for the Oscar-nominated Little Women, and finally all the way back to 1692 for The Crucible. All the while, her manner and sentiments underscored a modern intensity unmistakable even in the buttoned-up, propriety-obsessed past. Scorsese’s film, then, stands out as the clever exception requiring her to play against type; her May Welland, the naïve odd corner in a love triangle between Daniel Day-Lewis and Michelle Pfeiffer, doesn’t have the guile of a usual Ryder dame. She’s sharp enough to know something’s amiss but not enough to know what it is. The line above sounds like it might be a reassuring confirmation of her romance with Day-Lewis’s eligible bachelor, but she’s mostly saying the words to convince herself. Even in tamer times, Ryder could triangulate the pain.

“Don’t just dick around the same coffeehouse for five years.” –Reality Bites

For better and for worse, Ben Stiller’s dramedy about the interior lives of rudderless college graduates defines the slacker ’90s more adroitly than Slacker. Scores of eyeballs have been rolled at Ethan Hawke’s faux-philosophical beatnik Troy, but at least Ryder gave audiences someone they didn’t have to hold in contempt with her would-be documentarian Lelaina. She begins the film as the self-appointed voice of a generation, giving a valedictorian address fraught with unease about entering a culturally bankrupt society with no place for her. (“… And they wonder why we aren’t interested in the counterculture they invented, as if we did not see them disembowel their revolution for a pair of running shoes …”) By the final scenes, she arrives at the grown-up wisdom printed above, accepting that whining about the phoniness of adulthood is more of a hobby for lazy navel-gazers and not the purifying rebellion Troy imagines it to be. This is the sound of Ryder outgrowing the era of apathy, a time that made sarcastic smart alecks into A-list movie stars.

“Maybe the whole world is stupid and ignorant, but I’d rather be in it.” –Girl, Interrupted

But first, she’d have to be a teenager again. A 28-year-old Ryder believably played ten years younger as Susanna Kaysen, a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown. An unattended case of borderline personality disorder lands her in a mental institution for similarly troubled girls, most notable among them the sociopathic Lisa (Angelina Jolie, in the role that earned her the Academy Award). Lisa encourages her to resist drugs and therapy as the Man’s instruments of control, sending Susanna on a trajectory toward the willingness to be well. James Mangold’s film lent serious credence to what melodrama and after-school specials had made into caricature, a perfect thematic dovetail with a career Ryder used to expose the profundity contained in young women. Though it was a passage in the opening narration — “Have you ever stolen something when you had the cash?” — that would prophesy the next chapter in her career.

“He is not a dipshit! He is a kind, sweet-hearted guy who we think is a dipshit because he doesn’t have our sense of cynicism and negativity that we put into the news to make it sell!” –Mr. Deeds

A 2001 arrest for shoplifting led to a hiatus that lasted until 2005, the interim years dotted with some uncredited work and a pair of releases securely in the can prior to her withdrawal from the public eye. One of those was a remake of a 1936 Frank Capra feature in which Adam Sandler applied his man-child schtick to the story a small-town schlub turned billionaire, and snared $171 million in the process. How cruel that Ryder would have to spend the biggest hit of her career debasing herself as his utterly mismatched love interest, a scheming reporter summarily purified by his generosity and heart. Ryder’s saddled with some of the grisliest dialogue in the picture, forced to hold up the entire emotional backbone with a stirring final speech. As is the case with Ryder’s general participation in the production, it’s difficult to tell how much is intended ironically.

“Drippy little things, moving along, about a foot above the ground. Just dripping, behind furniture. Little spring flowers with blue in them might come up first.” –A Scanner Darkly

When Ryder got back in the game, it wasn’t as a leading lady for well-funded studio enterprises. She had to reinvent herself as an actress with humbler ambitions, the flip side of this transition being an interest in odd, unlikely projects that tested her range. Foremost among them was a high-concept thriller from Richard Linklater, who pulled his head out of the clouds just long enough to assemble a paranoid mystery mixing drug use and state surveillance with a surreal animation technique called interpolated rotoscoping. Even under a layer of artistic rendering, Ryder surgically flips from femme-fatale coquettishness to steely composition to something colder and more sinister with each new twist. Ryder’s character serves up the helping of word salad reproduced above in describing a cat, her inscrutable free verse hinting at significance yet to be revealed. The conviction with which Ryder delivers the words, however, announced an actress willing to go anywhere and try anything with her work.

“I’m not perfect. I’m nothing.” –Black Swan

As the generation that grew up idolizing Ryder has aged into the driver’s seat of the film industry, a number of projects have started to use her presence as a comment unto itself. Consider the upcoming Destination Wedding, which pairs her with her erstwhile Bram Stoker’s Dracula co-star Keanu Reeves, much to the delight of Coppola superfans, or Stranger Things, which wove her into its overall fetishism for ’80s and ’90s nostalgia. Darren Aronofsky tapped this referential well for his dance-world descent into madness, casting Ryder as the washed-up prima ballerina replaced by pert new model Nina (Natalie Portman). There’s a personal sting to a disturbing sequence that climaxes with Ryder stabbing herself in the face with a nail file as she screams about how quickly the public favor turns on a performer. She’d known the ups and downs of show business, felt it like the nightmare into which that scene swiftly pivots. The character drowns in her own self-loathing, furious at herself for ceding the spotlight, but one hopes the bona fide Ryder sees things more clearly. This month’s parade of hosannas alone proves it — her legacy is intact.