The superhero industry is built on an illusion. The big brands, Marvel and DC, would have you believe that their foundation stones are dashing characters and zip-pow stories. But those properties are only the second level — the true foundation is the unsung toil of freelance comic-book creators, operating on work-for-hire agreements without union protections, who crank out all those heroes, villains, and sagas. They hardly ever get their due because they don’t outright own the characters they create for Marvel or DC, and can thus usually can only hope for a “special thanks” credit on a film or television adaptation of one of their brainchildren. So perhaps I shouldn’t be shocked by what comics writer Marv Wolfman says to me.

I call him up to discuss Bullseye, the iconic supervillain he co-created for Marvel Comics with artist John Romita Sr. in the mid-1970s. “I’m writing a piece about Bullseye,” I tell Wolfman over the phone. “He’s one of the lead villains in the new season of Daredevil, so …” Before I can finish the sentence, Wolfman interjects: “He is?”

“Yeah!” I say. “No one told you?”

“No, no,” Wolfman replies, matter-of-factly. “Nobody told me. I mean, several fans said that, but they’d been saying that for months, so I assumed that was a rumor. I’ve been away for the last two weeks at conventions, so I haven’t been able to check the boards. I assumed it was a rumor.”

I’m genuinely taken aback. Really, Marvel? You couldn’t have shot a heads-up email to a man who is the sine qua non for the main plot arc of a sure-to-be-lucrative season of television? “Well,” I say, “I’m here to deliver the news that your co-creation is, indeed, in season three of Daredevil in a very prominent role.”

“That’s lovely,” he says. “I love that.”

As will fans of Wolfman’s brainchild — or so the show hopes. This Bullseye is a radically different interpretation from the one first seen in 1976’s Wolfman-penned Daredevil No. 131. That’s to be expected. The character underwent a remarkable evolution over the course of his time on the page well before he made it to the screen, so further change should come as no surprise. Bullseye has gone from a gimmicky one-off baddie produced during a lull in the history of Daredevil, to perhaps his greatest and most psychotic foe, to comic relief at the box office, and now to a gut-wrenchingly tragic (and rakishly handsome) figure that will be introduced to millions. The story of how he got there embodies the hidden collaborative process that powers superhero fiction.

Before we go any further, a myth from Wikipedia needs to be dispelled: This Bullseye is emphatically not the guy who tried to kill Nick Fury in 1969’s Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. No. 15. That issue, written by the late Gary Friedrich and drawn by Herb Trimpe, introduced a garishly dressed assassin named Bulls-Eye. His gestalt is adorably preposterous: In a sinister mid-story soliloquy, he reveals that he’s actually not much of a marksman and simply wields a gun that automatically finds its targets with pinpoint accuracy. Fury’s best bud Dum Dum Dugan (God bless comic-book names) shoots Bulls-Eye dead on the final page. We have yet to see him again, and due to potentially confusing nomenclature mix-ups, one doubts we ever will.

That doesn’t mean there wasn’t an antecedent to Wolfman and Romita’s killer. His prehistory lies in the pens of two of the most brilliant minds to ever make a comic book: Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. The duo were best known for creating Captain America in 1941, but in 1954, they struck out on their own and formed a company called Mainline. There, they launched four original titles featuring brand-new characters, one of which was an eponymous Western series about a “Western scout” — clad in bizarre green, red, yellow, and black — named Bullseye. Ask the 72-year-old Wolfman what he liked about the Kirby-Simon series and he’ll reluctantly admit, “I don’t think I ever read a Bullseye, but I always loved the graphic of him.” The name, too, stuck in his preteen Brooklynite brain.

It would prove useful once the lad grew up and became a professional comics writer. Wolfman got his start at DC in the late 1960s, but jumped ship to Marvel in 1972 to work under legendary writer-editor Roy Thomas, who was then the editor-in-chief. Thomas shocked the company by stepping down as EIC in 1974, leaving Wolfman and his pal Len Wein to co-run the show for a bit until Wolfman was given the full reins of the EIC role in 1975. He was still writing on a regular basis, so the pile on his plate was growing at an exponential rate. Nevertheless, when Daredevil writer Tony Isabella had to drop that series, Wolfman took up the task of penning it.

“I liked him,” Wolfman says of Daredevil, “but he, for the longest time, seemed to be a watered-down Spider-Man.” It’s a tough-but-fair accusation. Created by Stan Lee and Bill Everett and debuting in 1964, Daredevil — taglined as “the Man Without Fear” — had never garnered much of a following. His swashbuckling, zinger-filled, mildly superpowered antics in New York City were far from revolutionary. He was unique in that he had a disability, blindness, but even that wasn’t particularly relevant, given that the accident that blinded him enhanced his other senses to the point where he had a kind of sonar vision. He was a lawyer, too, and that could lead to some idiosyncratic situations, but the slam-bang house style of 1960s and ’70s Marvel didn’t lend itself to courtroom drama.

Wolfman wishes he could say he was the one who changed all of that and moved Daredevil into the spotlight, but he readily admits that that’s not the case. Though Wolfman is a man of enormous talents and is responsible for multiple turning points in comics history, his 14-issue run on Daredevil is not particularly well-remembered. Nevertheless, he did leave a mark in the form of the nasty man he introduced in issue 131. Though Bullseye’s character traits and dialogue style are now some of his most distinctive aspects, they were almost entirely absent in his first appearance. Wolfman was mostly just concerned with coming up someone who could lead to good fight scenes.

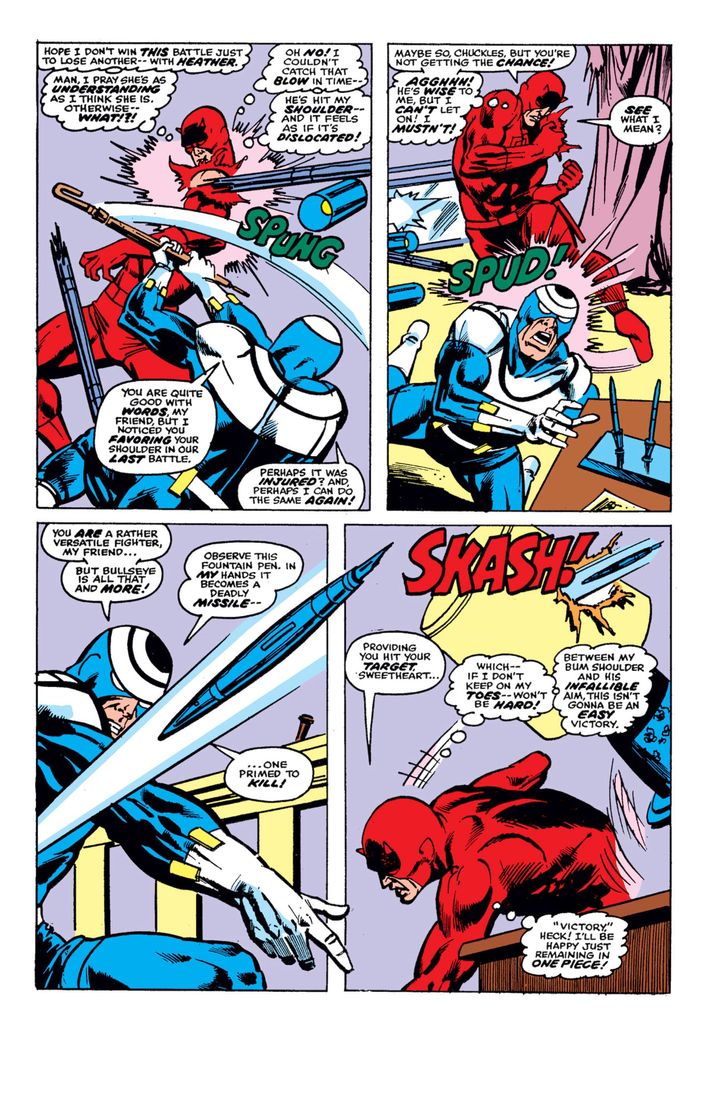

“We’re in the job of hurting people,” Wolfman says of superhero writers. “How does the villain tax the hero as much as possible? How does the villain create problems for the hero?” He had to craft an antagonist who could push DD to the limit. “Daredevil’s power is essentially that he can see things coming at him in radar vision,” says Wolfman. “Daredevil is great in hand-to-hand, close-quarters fighting because he can predict where the fighter is. But what if the villain is half a mile away? He may not sense him.” Ergo the notion of someone whose specialty was projectiles. But not just any projectiles — after all, Daredevil was pretty used to sensing and dodging bullets. “If you throw a pen and are capable of piercing his neck,” Wolfman says, “that wouldn’t be immediately conceived of. If you throw a paper plane at him, he may not spot that as a threat.” Therein lay the magic of Bullseye, the factor that defines his power set to this day: He can turn anything into a weapon. Whatever else changes about the guy, that notion is his bedrock.

Of course, comics are a visual medium, and no villain is worth its salt if it doesn’t look equal parts fun and menacing. Although Bullseye’s first published appearance came at the hands of unassuming artist Bob Brown (“a true gentleman, a really nice guy” is just about all Wolfman has to say about him), Brown didn’t actually come up with the character design. At the time, Romita and fellow superhero-art legend Dave Cockrum were the go-to artists for writers who needed a distinctive-looking new individual. Wolfman sketched out some crude ideas and brought them to Romita (who declined to be interviewed — at 89, he deserves a rest) at Marvel HQ on Madison Avenue. Genius that he was, Romita didn’t need much time to come up with something bold and unforgettable.

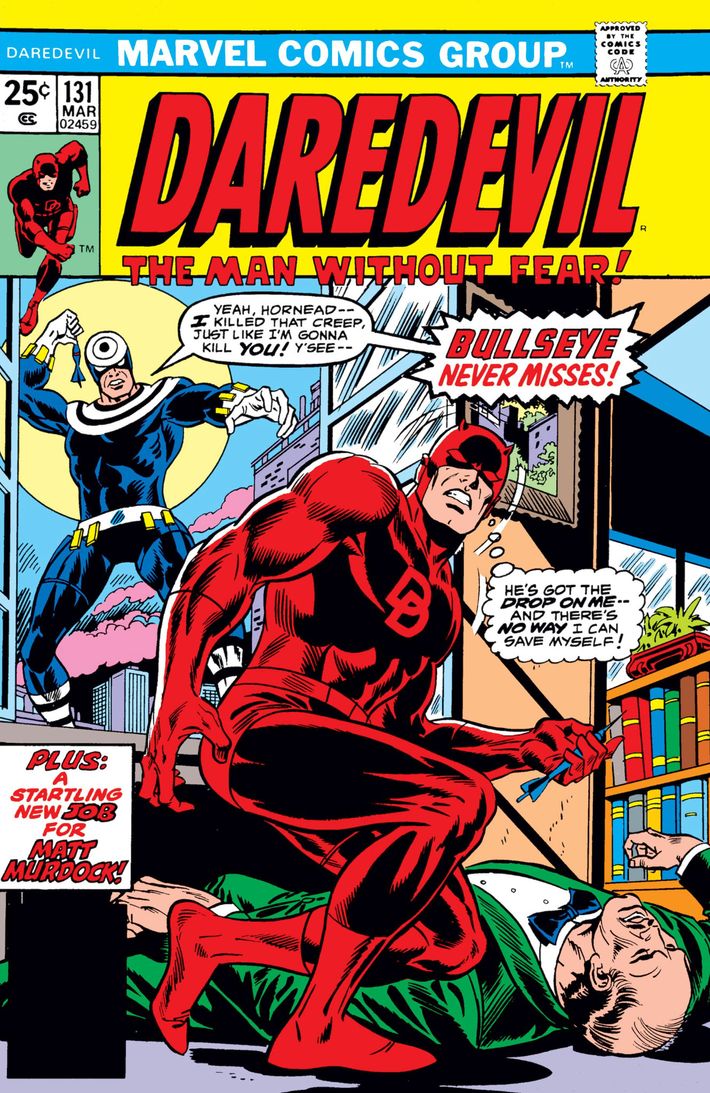

The design leapt into action on the cover of issue 131, which hit stands in January of our nation’s bicentennial year. While DD crouches over a corpse that has apparently been felled by a simple hand dart, a mysterious figure looms on a windowsill. He wears a skintight onesie of nearly all black, save for some white stripes on his ankles, a white-and-yellow utility belt, and — most notably — two massive black-and-white bull’s-eyes, one acting as a collar and the other emblazoned on the skull of his outfit’s mask. “Yeah, Hornhead,” this strange new villain yells while poised to toss another dart, “I killed that creep, just like I’m gonna kill you! Y’see — BULLSEYE never misses!”

The ensuing story, which took up that issue and the next one, is equal parts sinister and ridiculous. We first meet Bullseye as he menaces, attempts to extort, then kills a rich man in an office building. His tools of choice? Why, a paper airplane and a pen, of course. After investigating the crime scene, Daredevil gets some info from a veteran reporter who’s heard the straight dope about this Bullseye fellow. Apparently, he went war-mad while serving in the Korean War (this would later be retconned, in keeping with Marvel’s commitment to having its characters remain young) and became “a mercenary in Africa, perfecting his use of weapons and learning about new, strange, exotic ones, all of which, with his uncanny aim, were twice as deadly as before.” What’s more, “He wants … he craves publicity. Figures it will frighten his future victims into paying him off right away.”

The journo turns out to be right: Bullseye adores attention. He lures Daredevil into a trap and reveals that he’s brought the superhero to the center ring of a circus — he wants to defeat DD before a huge audience so they’ll recognize his own greatness. Bullseye’s dialogue is light-years away from what it would turn into later in his publication history. These days, he’s a slang-talking lowlife who’s prone to bad language; back in his original appearance, he’s an operatic monologuist with meticulous diction. “Daredevil, I have brought you here to this circus, that we may stage our most ferocious fight to the finish,” he declares while menacingly tossing juggling pins in the air, “a fight, I might add, that only one of us will survive! And Bullseye must be the victor!” After a bizarre tussle involving a rampaging elephant and a terrified circus performer being fired at DD out of a human cannon, our hero gets the best of Bullseye simply by being a tougher hand-to-hand brawler and delivers the bad boy to the cops. The end.

… or was it? Bullseye returned a handful of times in the next three years, never terribly memorably. Wolfman and Brown had him come back for a brief cameo in which he acted more or less like a villain from the 1960s Batman TV show, firing DD out of a giant crossbow on a massive arrow while dropping quips such as “Farewell, old friend. I’d like to say it’s been fun — but I never mix business with pleasure! Ta ta!” When Wolfman departed the series, fill-in writer Jim Shooter did a story where Bullseye attacked Daredevil in a wrestling ring during a live TV broadcast. He was still in the realm of goof-off villains like Stilt-Man and Batroc the Leaper: a member of the rogues’ gallery, but one who was mostly good for a laugh.

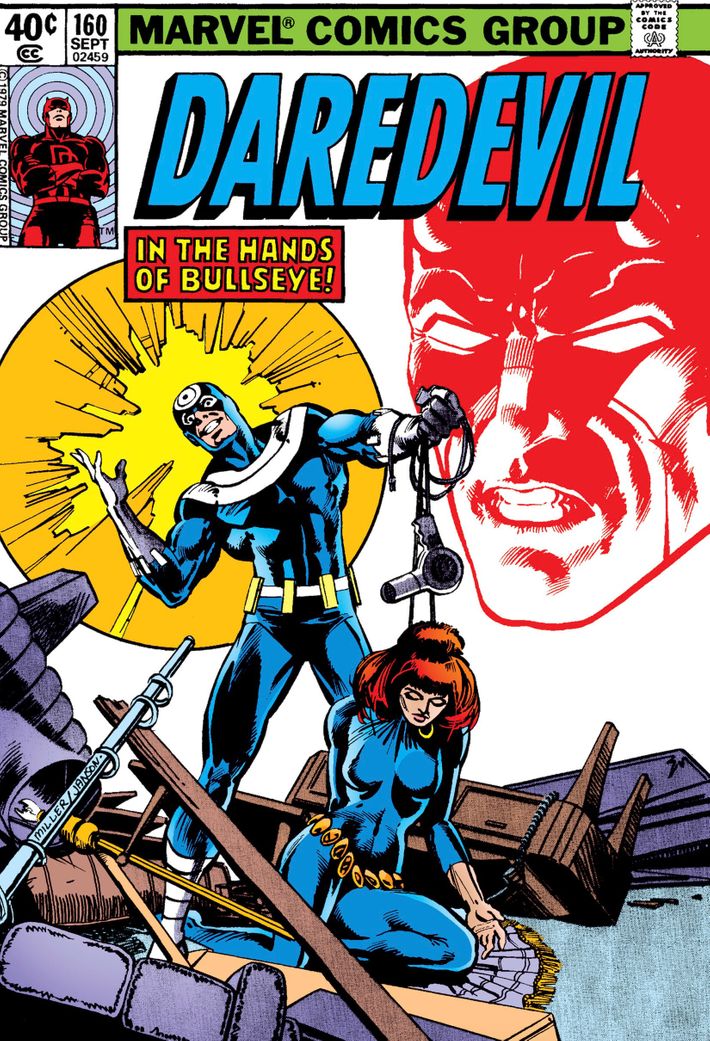

Then came the blow-dryer. Writer Roger McKenzie took over the series and told a three-parter in the summer of 1979. It began goofily enough: A vengeance-seeking Bullseye, operating under the alias Benjamin Poindexter, hires some gangsters to attack Daredevil, not so they’ll kill him but so he can capture the fight on film and study DD’s moves. However, chapter two features him using his newfound skills to attack Daredevil’s sometimes-paramour, Black Widow. The cover of issue 160 was shocking to readers of the time: A deranged-looking Bullseye stands amidst the wreckage of a living room, holding a blow-dryer cord that he’s wrapped around the neck of Widow’s limp body. The subsequent story was fine — Bullseye nabs Widow, brings her to an amusement park, and he and DD duke it out there until our hero intimidates Bullseye to a point where he starts to have a mental breakdown — but the jarring image on the cover of that first part was where the real action was at. It was drawn by two men who would, in short order, go on to transform Daredevil and Bullseye forever: penciler Frank Miller and inker Klaus Janson.

They took power in one of the great gambles in comics history. Miller was notoriously frustrated with McKenzie’s scripts, but editor Denny O’Neil had a good feeling about the young Irish Catholic cartoonist. Though Miller had no reputation as a writer, O’Neil took McKenzie off the book and gave Miller the reins to write Daredevil himself, soup to nuts. “At that point, Daredevil was a really poor seller,” recalls Janson — in other words, there wasn’t much to lose. So from issue 168 on, Miller and Janson were the creative forces on the title. O’Neil’s bet paid off. Miller had cut his teeth writing detective stories and his ascent coincided with a relaxing of editorial standards for dark storytelling. The result of that alchemy was one of the first so-called “grim and gritty” takes on a superhero ever put to paper. “Frank did a 360 on the character and made you rethink everything you knew,” Wolfman says. “He was a perfect fit for Daredevil, and I wasn’t.”

Miller was also, as it turned out, a perfect fit for Bullseye. The baddie’s first story in the Miller era came in issue 169, a story called “Devils.” It’s a chiller to this day. The gist is simple: It’s revealed that Bullseye has acted so eccentrically all these years because he’s been suffering from a brain tumor, and after he escapes from prison, the tumor and the trauma of his experiences with DD cause him to see every single human being as Daredevil. “They’ve done it! They’ve finally done it! The devils have taken over!” he thinks to himself, face clutched in his hands, amid a Miller-and-Janson-drawn winter street scene of men, women, and children in Daredevil costumes making their way through Times Square. The issue is classic Miller, equal parts humorous and terrifying, and concludes with DD contemplating allowing Bullseye to be killed by an oncoming train before opting to save him. It is an act of mercy for which the villain will never forgive his savior.

Over the course of the next few issues, Bullseye finally became who he would end up being for the rest of his comics existence. His tumor is removed and, all of a sudden, he’s goes from wacko goofball to hard-bitten, darkly wisecracking killer. We see him toss Daredevil out of a window while saying he can use anything as a weapon, including New York City itself. We see him lounge around some mafiosi while firing a paper clip into the air to kill a fly with perfect precision. We see him casually torture some lowlifes in an effort to find a target (“Willy, it’s been a long night. Full of fun. But I’m getting bored. And when I get bored, I kill things”). Miller and Janson’s thick blacks and stark whites were perfect for the bad guy’s chiaroscuro costume, and Miller knew exactly how to draw that cynical half-smile.

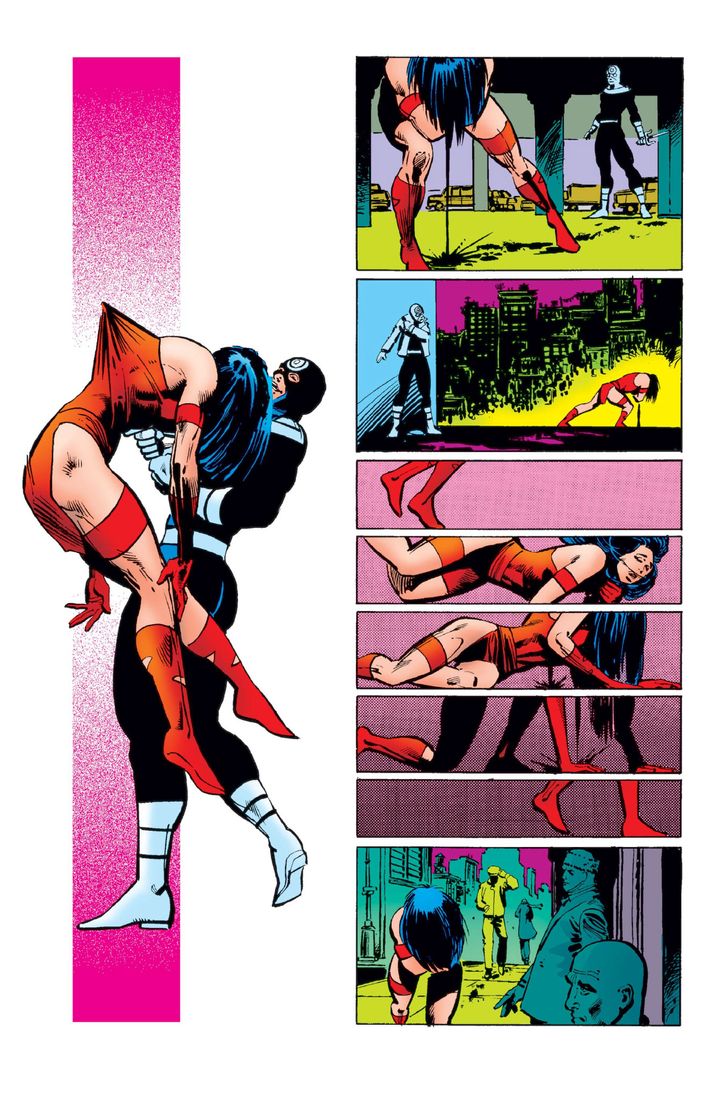

Bullseye reached his apex in the venerable 181st issue, “Last Hand,” where we hear his internal monologue about hating DD for not letting him die on the train tracks, then see him escape prison and murder the love of our hero’s life, the ninja super-assassin Elektra. The last words she hears are her killer muttering, through a toothy smile, “And, for my next trick …” Turn to the next page and you see Miller and Janson at their finest, showing us Bullseye stabbing Elektra through the gut with her own blade. It’s hard to overstate the impact this moment had on readers of the time, back when the good guys rarely lost so gorily. “When he killed Elektra in the comics, you realized, Oh, this is a hero-killer,” says Marvel television chief and longtime comics writer Jeph Loeb. “That’s a very rare commodity.” A livid Daredevil finds Bullseye and eventually drops him from the top of a high wire, crippling his foe. “My spine is shattered,” Bullseye thinks to himself from a hospital bed. “I can’t feel my arms or legs. I can’t even talk. But, man, can I hate. I hate you more than ever. And that’ll be enough.”

Though his body healed, his comic-book personality has stayed more or less the same ever since then. He’s become a perennial villain, popping up to antagonize a wide array of protagonists, but he always comes back to Daredevil. “If we were gonna follow a Batman comparison, I think that Bullseye is Daredevil’s Joker,” Janson says. When DD made the leap to the silver screen in 2003’s Daredevil, a Colin Farrell–played Bullseye was the lead’s most lethal combatant — albeit one also played as a quirky goofball whose murders were often comical. “Bullseye was always the ultimate Daredevil villain to me: A Man Without Fear vs. A Man Who Can’t Miss,” says that film’s writer-director, Mark Steven Johnson. “He could use guns if necessary, but that took all of the ‘fun’ out of killing. Bullseye took pleasure in finding new and interesting ways to kill people using ordinary, everyday objects. A paper clip. A playing card. A pencil. He even used a peanut on an airplane to choke an old woman to death.” In other words, Bullseye has an irresistible combination of sociopathy and innovation. The sheer danger of being in his vicinity and the anticipation of just how he’s going to off someone makes his appearances a thrill. “The best villains,” says Johnson, “have a way of seducing you.”

He certainly seduced Erik Oleson. Shortly after Oleson was installed as showrunner for season three of Netflix’s Daredevil, Loeb presented him with a few story line options that Marvel TV had been mulling, one being a Bullseye arc. Though he’s literate in comics, Oleson came to them later in life and didn’t have an encyclopedic knowledge of the DD canon. However, the more he read about Bullseye, the more he felt he’d found fertile ground.

“One of the things that made him really appealing to me was that his backstory was not set in stone,” Oleson tells me. It’s true — there is no firmly established origin for Bullseye in the comics. Hell, we don’t even know his real name. There was that bit about the Korean War in his introduction, but that never got explored further. Writer Peter Milligan tossed off the notion of an abusive father in an issue of an Elektra solo series in the ’90s. A Kevin Smith–penned issue in 2002 had a possibly-bullshit revelation that his name is Lester. Writer Daniel Way had Bullseye recount his life story to a pair of G-men in a 2004 mini-series called Bullseye: Greatest Hits, only to have it revealed that he’s making an undisclosed amount of it up as he goes along, just to screw with his interrogators. “With Bullseye,” Way says, “there’s always an angle.”

Given all that, Oleson and his team had carte blanche to come up with whatever they wanted. In the six episodes released to the media prior to the third season’s launch, it appears that they took the basic idea of a mentally damaged man who can turn anything into a weapon and never misses, threw everything else out, and started from the ground up. This Bullseye doesn’t even go by that name — he’s FBI agent Benjamin “Dex” Poindexter, a master marksman who starts out with an uneasy stability and grows increasingly unsteady as his troubles mount and he comes into the orbit of master criminal Wilson Fisk. Oleson says he and his staff consulted with mental-health professionals to explore realistic depictions of dissociative disorders, borderline-personality disorder, and sociopathology, all in an effort “to be both sensitive and realistic.” Played by Hart of Dixie’s Wilson Bethel, Dex (at least so far) bears little resemblance to the wiseacre lowlife comics readers have come to know, except in his set of abilities. It remains to be seen whether these deviations will turn out to be a bridge too far for die-hard originalists.

But that’s the question for any superhero-comics adaptation, really. These pieces of property go through so many stewards over their decades of existence that any storyteller has to weigh the comparative risks of being too faithful to the past or being too risky in their experimentation. For his part, Wolfman isn’t precious about what’s happened to his creation. He’s not even particularly upset that Marvel didn’t tell him they were using his brainchild. As it turns out, though he never quite got a feel for Daredevil while writing him, he’s a big fan of his televised incarnation. When I ask if he’s planning to watch the show that partially snubbed him (to be fair, he does get a special thanks in the credits), he has a cheery reply: “Oh, I would always watch Daredevil,” he says. “I loved the first two seasons. Daredevil and Jessica Jones are my two favorites, and Luke Cage. I don’t watch any of the others.” (Sigh, hasn’t Iron Fist been through enough abuse?)

Wolfman actually got to take another stab at Bullseye just last year, doing a short backup story for the first issue of a short-lived Bullseye solo series. His 2017 take was significantly grittier and more violent than anything he did with the character back in the day, but that transition is a credit to Wolfman’s talents: He can still find the guy’s rhythm, even though the tempo has drastically changed. It’s almost like Bullseye is Wolfman’s inverse: where the creation is vicious, conceited, and egomaniacal, the creator is gentle, giving, and humble. When I ask him to sum up his time writing Daredevil and its titular hero’s greatest nemesis, you can almost hear the shrug over the phone. “I enjoyed what I did,” he says. “I don’t think I did anything special.”